Overview

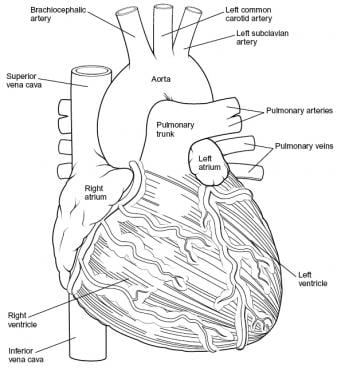

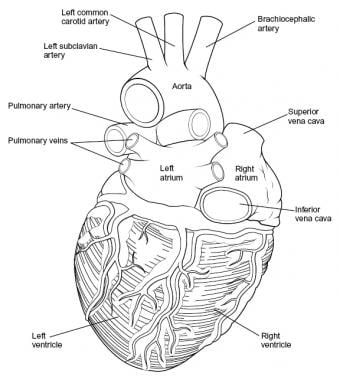

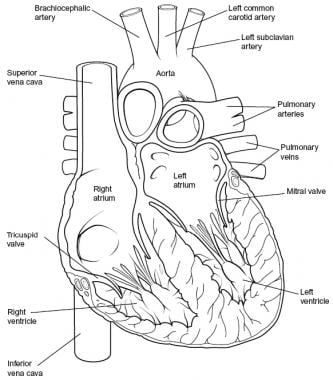

Intraoperatively, the anatomy of the heart is viewed from the right side of a supine patient via a median sternotomy incision. The structures initially seen from this perspective include the superior vena cava, right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery, and aorta. Medial displacement of the right side of the heart exposes the left atrium and right pulmonary veins. Medial rotation from the left exposes the left ventricle apex, left pulmonary veins, and left atrium (see the images below).

The overall shape and position of the heart may vary according to the relative size and orientation of each of its parts. For example, a large right ventricle may allow exposure of only a short segment of aorta; this is because of the narrow confines of the middle mediastinal space. The average heart dimensions may differ based on factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity. [1]

Intraoperative mapping techniques help locate critical conduction pathways such as the bundle of His during complex congenital heart disease surgeries. This helps localize the conduction system, thereby minimizing complications such as heart block. [2, 3]

Cardiac Chambers

Right atrium

The superior vena cava and inferior vena cava drain systemic venous blood into the posterior wall of the right atrium. The internal wall of the right atrium is composed of a smooth posterior portion (into which the venae cavae and coronary sinus drain) and a ridgelike, muscular anterior portion. The crista terminalis is a prominent C-shaped ridge of muscle. It separates the smooth-walled portion of the atrium from the trabeculated portion. [2]

The coronary sinus drains coronary venous blood into the anteroinferior portion of the right atrium. The thebesian valve located at the orifice of the coronary sinus plays a role in preventing retrograde flow during atrial contraction. [2] The limbus of the fossa ovalis is located on the medial wall of the right atrium and circumscribes the septum primum of the fossa ovalis anteriorly, posteriorly, and superiorly (see the image below).

The right auricle is separated from the right atrium by a shallow posterior vertical indentation on the right atrium (i.e., the sulcus terminalis) and by a vertical crest internally (i.e., the crista terminalis) that separates the right atrium into trabeculated and nontrabeculated portions.

Congenital anomalies of the right atrial components can be associated with clinically significant cardiac malformations. For example, in patients with tricuspid atresia, the Eustachian and thebesian valves may be so enlarged that they physically separate the right atrium into two distinct sections. Other variations include juxtaposition of both atrial appendages and malpositioning of both appendages.

Left atrium

Compared with the right atrium, the left atrium has thicker walls which allows it to effectively manage blood flow into the left ventricle. The four pulmonary veins (right and left superior and inferior) drain into the superior part of the left and right posterolateral surfaces of the left atrium. These veins are positioned symmetrically on either side of its posterior wall. In some cases, these veins may merge into a common ostium before entering the atrium, which is significant for both anatomical understanding and clinical considerations, particularly in procedures such as catheter ablation. [2, 4, 5]

The flap valve of the fossa ovalis is located on the septal surface of the left atrium. This structure is a remnant of the embryonic foramen ovale, which allows blood to bypass the nonfunctioning fetal lungs. The flap can serve as a functional valve in certain conditions. [2, 6]

The appendage of the left atrium is consistently narrow and long; identification of this appendage is the most reliable way to differentiate the left atrium from the right atrium. The left atrial appendage is the only trabeculated structure in the left atrium because, unlike the right atrium, the left atrium has no crista terminalis. This trabeculation is important as it contributes to the risk for thrombus formation in patients with atrial fibrillation, with studies indicating that over 90% of thrombi in nonvalvular AF originate from this area. [5] The morphology of the left atrial appendage significantly influences thrombus formation risk. Studies have shown that specific geometric configurations can predispose patients to stroke, highlighting the importance of understanding this anatomy in clinical practice. [5]

The size and function of the left atrium are critical indicators in various cardiac conditions. For instance, an enlarged left atrium is associated with increased risks for heart failure and stroke, particularly in patients with mitral regurgitation. Evaluating left atrial volumes through imaging techniques has become essential for assessing cardiac function and guiding treatment strategies. [2, 7]

Right ventricle

The right ventricle is located anteriorly and slightly to the left. The chamber is designed to handle the lower pressures of pulmonary circulation, which contributes to its relatively thin walls compared with the left ventricle. Internally, the right ventricle is divided into inflow and outflow tracts separated by the crista supraventricularis. [2]

The right ventricle receives blood from the right atrium across the tricuspid valve, which is located in the large anterolateral (i.e., sinus) portion of the right ventricle. The right ventricle discharges blood into the pulmonary artery across the pulmonic (semilunar) valve located in the outflow tract (infundibulum). The inflow tract (sinus) and outflow tract (infundibulum) of the right ventricle are widely separated.

Internally, the sinus area and infundibulum contain coarse trabeculations. The septal portion of the right ventricle has three components:

(1) The inflow tract, which supports the tricuspid valve and is crucial for directing blood flow from the right atrium [2]

(2) The trabecular wall, which typifies the internal appearance of the right ventricle

(3) The outflow tract, which itself is subdivided into three components, namely the conal septum, septal band division, and trabecular septum. Of these three subdivisions, the conal septum is clinically significant because it can be malpositioned in patients with congenital disorders (e.g., double outlet right ventricle (DORV)).

Lateral to the conal septum, the parietal extension of the infundibular septum and the infundibular fold comprise the crista supraventricularis. Ventricular septal defects (VSDs) commonly occur in the area between the sinus and the outlet tract of the right ventricle. However, because the surface of the right ventricle is trabecular, small defects of the muscular portion of the ventricular septum may be difficult to see.

The tricuspid valve is supported by a large anterior papillary muscle, which arises from the anterior free wall and the moderator band, and by several small posterior papillary muscles, which attach posteriorly to the septal band.

Pathologies such as pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular hypertrophy, and right ventricular failure are closely associated with stress on the right ventricle due to prolonged high pressures, leading to adaptive changes such as increased myocardial thickness and potentially, right ventricular failure. [8, 9]

The right ventricle's structure is essential for its adaptation to pulmonary circulation, and various congenital malformations, such as VSDs or DORV, can disrupt this function. [9, 10]

Left ventricle

The left ventricle receives blood from the left atrium via the mitral (i.e., bicuspid) valve and ejects blood across the aortic valve in the aorta. This chamber is uniquely structured to handle the high pressures required to pump blood throughout the systemic circulation, making its walls significantly thicker, approximately three times, than those of the right ventricle. [2]

The left ventricle can be divided into two primary portions, namely:

The large sinus portion containing the mitral valve and the small outflow tract that supports the aortic (semilunar) valve. The inflow and outflow portions are closely juxtaposed, unlike in the right ventricle, in which the tricuspid and pulmonic valves are widely separated.

The free wall and apical half of the septum contain fine internal trabeculations. The septal surface is divided into a trabeculated portion (sinus) and a smooth portion (outflow). The sinus area just beneath the mitral valve is termed the inlet septum; the remainder of the sinus area is termed the trabecular septum. The outflow tract is located anterior to the anterior mitral leaflet and is part of the atrioventricular (AV) septum. Both the right half of the anterior mitral valve leaflet and the right aortic cusp attach to the septum; in the right ventricle, only the septal tricuspid leaflet attaches to the septum.

The left half of the anterior mitral leaflet is in direct, fibrous contact with the aortic valve at the aortic-mitral annulus. The conal septum of the right ventricle is positioned opposite the aortic valve. The mitral valve is supported by two large papillary muscles (i.e., anterolateral, posteromedial) attached to the chordae tendineae that prevent valve prolapse during ventricular contraction. [2] The anterior papillary muscle is attached to the anterior portion of the left ventricular wall, and the posterior papillary muscle arises more posteriorly from the ventricle's inferior wall, both crucial for maintaining proper closure of the mitral valve during systole. [11, 2]

The left ventricle's efficiency in pumping blood relies on its unique structural adaptations. Studies have highlighted that the human left ventricle morphology features less trabeculation and a more compact myocardium. This evolutionary change enhances cardiac output and supports metabolic demands associated with bipedalism and a larger brain size in humans. [12]

Circumferential fiber shortening reflects myocardial performance and is influenced by preload and afterload conditions. Increased wall stress can lead to left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), which may result from chronic pressure overload conditions such as hypertension or aortic stenosis. [13]

Great Vessels and Septi

Aorta

The aorta originates at the base of the heart, specifically from the left ventricle, and ascends through the superior mediastinum before arching posteriorly and descending into the thorax. It typically branches into the coronary arteries just distal to the aortic valve. [14, 15]

In patients with cardiac malformations, the aorta can almost always be identified by tracing it back from the brachiocephalic arteries, which only very rarely originate from the pulmonary artery.

Aortic arch anomalies are classified into several categories based on their embryological development and anatomical features. The most common variants include: [14]

-

Left aortic arch

-

Right aortic arch

-

Double aortic arch

-

Cervical aortic arch

These variations can have varied impacts that may range from asymptomatic to airway compression or vascular issues. Imaging techniques such as multidetector computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have become essential for diagnosing these anomalies, often revealing these variants as incidental findings during evaluations for other conditions. [14]

The presence of aortic arch anomalies is frequently associated with other congenital heart defects (CHDs) and chromosomal abnormalities. For example, congenital aortic valve stenosis, one of the most prevalent valve anomalies, is noted to occur in 3-6% of cardiac malformations and often requires surgical intervention due to its progressive nature. [15]

Pulmonary artery

The main pulmonary artery originates from the right ventricular outflow tract and is responsible for transporting deoxygenated blood to the lungs. It typically measures about 5 cm in length and has a diameter of approximately 3 cm. As it courses posteriorly and superiorly, it lies to the left of the ascending aorta, with which it is initially enveloped by the serous visceral pericardium before fusing with the vessel adventitia. At the level of the carina (around T6), the pulmonary trunk bifurcates into the right and left main pulmonary arteries, which further divide into lobar and segmental branches that supply the lungs. [2, 16, 17]

In patients having aberrant cardiac anatomy with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), accurate identification of the pulmonary artery can be difficult using angiography because the pulmonary artery becomes opaque during aortic injection. To differentiate the pulmonary artery from the aortic valve, it is essential to remember that the pulmonary artery almost never gives off brachiocephalic branches.

Studies highlight significant anatomical variations in the pulmonary arterial system. Analysis of CT angiographic data revealed diverse branching patterns within both pulmonary lobes. In a study involving 420 subjects, notable variations were observed in the left superior pulmonary artery, where multiple arteries supplied blood to specific lobes. The right upper lobe commonly exhibited two arteries supplying its segments. [18]

Research emphasizes the implications of PDA on pulmonary circulation. It has been shown that significant PDA can lead to increased pulmonary blood flow, contributing to conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in neonates. This relationship highlights the need for careful monitoring and management of PDA in vulnerable populations as prolonged exposure may adversely affect lung development and function. [19]

Ventricular septum

The ventricular septum is divided into a muscular section (inferior) and a membranous section (superior).

The muscular portion of the ventricular septum is primarily composed of cardiac muscle and forms the bulk of the septum. It contributes significantly to the structural integrity of both ventricles, facilitating their mechanical function during the cardiac cycle. This muscular septum typically has a thickness of approximately 9 mm in women and 10 mm in men, playing a vital role in maintaining the pressure differential necessary for effective ventricular contraction. [20]

The membranous septum, also termed the pars membranacea, is a fibrous structure partially separating the left ventricular outflow tract from the right atrium and ventricle. This section is significantly thinner than the muscular part and serves as an important site for various clinical conditions, including VSDs. The membranous septum is integral to the conduction system of the heart, housing parts of the bundle of His that facilitate electrical conduction between the ventricles. [20]

The anatomy of the ventricular septum is also critical during surgical interventions. The proximity of the conduction system to both sections of the septum necessitate careful consideration during procedures such as VSD closure or valve replacements to avoid damaging these essential structures. [20]

VSDs are among the most common congenital heart defects, often classified based on their location within the septum: [21]

-

Perimembranous VSDs - Located near the membranous septum, these account for about 80% of VSDs.

-

Muscular VSDs - Found within the muscular portion, these can vary greatly in size and location.

-

Outlet VSDs - Situated beneath the pulmonary valve, these are less common but can lead to significant hemodynamic consequences.

Studies have highlighted that VSDs can lead to left-to-right shunting of blood, resulting in increased pulmonary blood flow and potential complications such as pulmonary hypertension if not addressed. [21]

Atrioventricular septum

The AV septum, located behind the right atrium and left ventricle, is divided into two portions: a superior portion (membranous) and an inferior portion (muscular).

The bundle of His exits the AV node and penetrates the right fibrous trigone and runs underneath the membranous septum. [22]

Inside the left ventricle, the muscular component makes up part of the outlet septum. The AV node lies in the atrial septum, juxtaposed to the membranous and muscular portions of the AV septum. It is situated within the triangle of Koch, bordered anteriorly by the insertion of the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve and posteriorly by a fibrous structure known as the tendon of Todaro. [22]

Studies highlight that variations in anatomy can significantly impact the electrophysiologic outcomes during procedures such as permanent pacing. For instance, research indicates that there are notable interindividual differences in the location where the AV node transitions into the nonbranching component of the His bundle, which can affect pacing strategies. A majority of this transition occurs superiorly within Koch's triangle, while in others, it is found at or below the hinge line of the tricuspid valve's septal leaflet. [23]

Conduction System

Sinus node

The sinoatrial (SA) node occupies an area of 1-2 cm on the lateral surface of the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium near the crista terminalis. The sinus node is found superficially at the anterolateral aspect of the junction between the superior vena cava and the right atrial appendage. In rare cases, the SA node may be found medially along the ridge of the atrial-caval junction. [24, 25, 26]

The SA node is the primary pacemaker of the heart. Anatomically, this node has a crescent or comma shape, with its head located superiorly near the superior vena cava and its tail extending inferiorly along the crista terminalis. The node's length varies from 10-30 mm, width from 5-7 mm, and thickness from 1-2 mm. [27, 28]

Studies have revealed that the SA node has a complex, intramural structure extending from the epicardium to the endocardium. It consists of a compact core of specialized pacemaker cells surrounded by transitional tissue that interfaces with the adjacent atrial myocardium. [28] The blood supply to the SA node is provided by the SA nodal artery, which originates from the right coronary artery (RCA) or less commonly from the left circumflex (LCX) artery. [29]

Histologically, SA nodal cells are smaller than working atrial myocytes and have fewer myofibrils. They are embedded in a dense connective tissue matrix, which contributes to their electrical insulation from the surrounding atrial tissue. Studies have also identified specialized conduction pathways, known as SA conduction pathways (SACPs), that connect the SA node to the surrounding atrial myocardium. These SACPs play a crucial role in allowing the small SA node to effectively pace the much larger atria. [30]

Internodal pathways

The internodal pathways are specialized atrial muscle bundles that facilitate rapid conduction of electrical impulses from the SA node to the AV node. [2] The spread of electrical activation from the sinus node extends toward the AV node via Purkinje-like pale cells in atrial muscle bundles. These cells express higher levels of connexin 40 and connexin 43, facilitating rapid impulse propagation. [31]

Three main internodal pathways have been identified: [32]

-

Anterior internodal pathway - Originates from the anterior margin of the SA node, courses anteriorly around the superior vena cava, and gives off Bachmann's bundle before continuing to the AV node.

-

Middle internodal pathway - Arises from the posterosuperior margin of the SA node, passes behind the superior vena cava, and enters the interatrial septum to reach the AV node.

-

Posterior internodal pathway - Emerges from the posterior margin of the SA node, travels along the crista terminalis, and enters the interatrial septum above the coronary sinus to reach the AV node.

Anterior, medial, and posterior interatrial conduction pathways arise from the SA node. The anterior and medial pathways are located anterior and posterior to the foramen ovale; the posterior pathway is situated caudal to the foramen ovale.

Studies have highlighted the importance of internodal pathways in maintaining normal atrial conduction and preventing arrhythmias: [32]

-

They ensure rapid and coordinated activation of the atria.

-

Disruption of these pathways can contribute to atrial fibrillation and other supraventricular arrhythmias.

-

The anterior internodal pathway, particularly Bachmann's bundle, plays a crucial role in interatrial conduction and left atrial activation.

Atrioventricular node

The AV node is situated directly on the right atrial side of the central fibrous body in the muscular portion of the AV septum, just superior and anterior to the ostium of the coronary sinus. Measuring approximately 0.1 cm x 0.3 cm x 0.6 cm, the node is flat and oval. The node's left surface is juxtaposed to the mitral anulus.

The AV node is located in the paraseptal endocardium of the right atrium at the apex of the Triangle of Koch. Morphologically, the AV node can be subdivided into two main parts: [33]

-

The compact node (CN)

-

The lower nodal bundle

From the lower nodal bundle, two extensions spread out: [33]

-

The rightward inferior nodal extension (INE), which extends along the tricuspid valve toward the coronary sinus

-

The leftward nodal extension, which spreads from the CN along the tendon of Todaro

Synchrotron radiation-based x-ray phase-contrast computed tomography (PCCT) has revealed that the AV node is located adjacent to the right fibrous trigone. The median distance from the AV node to the mitral annulus was found to be 2.0 mm (range, 0.9-3.0 mm). In hearts with normally related great arteries, the AV conduction axis (AVCA) lies beneath the commissure of the aortic valve between the left-facing sinus and the non-facing sinus (NFS), extending to the nadir of the NFS. The median distance from the aortic valve to the AVCA was measured at 1.9 mm (range, 1.3-3.1 mm). [34]

Blood supply to the AV node comes from the RCA in most individuals, with autonomic innervation to modulate conduction speed as needed. Histologically, the AV node consists of various cell types, including rounded cells, transitional cells, Purkinje cells, and myocardial cells. The pacemaker cells within the node are oval-shaped, containing sparse and randomly organized myofibrils with numerous sarcoplasmic reticulum. This enables it to slow the conduction, allowing time for the atria to contract before ventricular excitation. [35]

Studies highlight that while the AV node is similar to the SA node, the former features unique cell distributions that further enhance its functional adaptability. For example, fewer Purkinje-like cells are present in the AV node, but it possesses a high concentration of transitional cells to support gradual signal propagation. This structural specificity enables its role as a "gatekeeper" in cardiac electrophysiology, coordinating atrial and ventricular contraction timing to maintain efficient cardiac output. [36]

Research has also identified the presence of an intrinsic GABAergic system within AV node pacemaker cells (AVNPCs), which plays a crucial role in regulating electrical conduction from the atria to the ventricles. [37]

His bundle and bundle branches

The AV node continues onto the His bundle via a course inferior to the commissure between the septal and anterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve. The bundle follows a course along the inferior border of the membranous septum and gives off fibers that form the left bundle branch (LBB) near the aortic valve. The His bundle is located on the left side of the ventricular septum in 80% of the patients. In the 20% of patients in whom the bundle is on the right side of the septum, the His bundle is connected to the left bundle by a narrow stem.

Studies have identified three common anatomical variations in the His bundle course relative to the membranous septum: [38]

-

Type I (47%) - Runs along the lower border of the membranous septum, covered by a thin myocardial layer

-

Type II (32%) - Courses within the interventricular muscle, separate from the membranous septum

-

Type III (21%) - Runs directly beneath the endocardium on the membranous septum ("naked" bundle)

The His bundle bifurcates into the LBBs and right bundle branches (RBBs) near the crest of the muscular interventricular septum. [39]

Left bundle branch: [39]

-

Originates as the His bundle emerges from the central fibrous body

-

Typically divides into three fascicles (anterior, posterior, and septal)

-

Forms an extensive subendocardial network with many interconnections

-

The LBB further subdivides into several smaller branches that begin at the ventricular septal surface and radiate around the left ventricle.

Right Bundle Branch:

-

The RBB originates from the His bundle near the membranous septum and courses along the right ventricular septal surface, passing toward the base of the anterior papillary muscle.

Research has emphasized the specialized structure and function of these bundle branches. They are lined with connective tissue and rely on Purkinje fibers and cell junctions to manage conduction timing and synchronization. These fibers facilitate fast conduction while preventing arrhythmias, though they can also be involved in reentrant circuits that contribute to ventricular fibrillation under certain conditions. [40]

Cardiac Valves

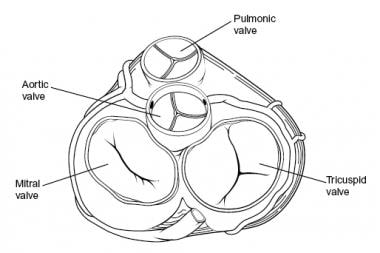

Cardiac valves are categorized into two groups based on their function and morphology. Mitral and tricuspid valves make up the AV group; aortic and pulmonary valves make up the semilunar group. On cross section, the aortic valve is located in a central location, halfway between the mitral and tricuspid valves. The pulmonary valve is positioned anterior, superior, and slightly to the left of the aortic valve. The tricuspid and mitral annuli merge and fuse with each other and with the membranous septum to form the fibrous skeleton of the heart (see the image below).

Mitral valve

The AV valve of the left ventricle is bicuspid. The AV valve has a large anterior leaflet (septal or aortic) and a smaller posterior leaflet (mural or ventricular). The anterior leaflet is triangular with a smooth texture. The posterior leaflet has a scalloped appearance. The chordae tendineae to the mitral valve originate from the two large papillary muscles of the left ventricle and insert primarily on the leaflet's free edge.

Studies have revealed intricate microstructural arrangements within the mitral valve leaflets, including a network of elastin and collagen fibers that contribute to their biomechanical properties. [41]

Tricuspid valve

The AV valve of the right ventricle has anterior, posterior, and septal leaflets. The orifice is larger than the mitral orifice and is triangular. The tricuspid valve leaflets and chordae are more fragile than those of the mitral valve. The anterior leaflet, largest of the three leaflets, often has notches. The posterior leaflet, smallest of the three leaflets, is usually scalloped. The septal leaflet usually attaches to the membranous and muscular portions of the ventricular septum.

A major factor to consider during surgery is the proximity of the conduction system to the septal leaflet. The membranous septum lies beneath the septal leaflet, where the His bundle penetrates the right trigone beneath the interventricular membranous septum. Moreover, the portion of the septal leaflet between the membranous septum and the commissure may form a flap valve over some VSDs.

Aortic valve

The aortic valve has three leaflets composed of fragile cusps and the sinuses of Valsalva. Thus, the valve apparatus is composed of three cuplike structures that are in continuity with the membranous septum and the mitral anterior leaflet. The free end of each cusp has a stronger consistency than the cusp. The midpoint of each free edge contains the fibrous nodulus Arantii, which bisects the thin crescent-shaped lunula on either side.

The aortic sinuses of Valsalva are three dilations of the aortic root that arise from the three closing cusps of the aortic valve. The right and left sinuses give rise to the right and left coronary arteries; the noncoronary sinus has no coronary artery. The walls of the sinus of Valsalva are much thinner than those of the aortic wall, which is a factor of surgical significance; therefore, aortotomies are typically performed away from this region.

The aortic annulus is situated anteriorly to the mitral valve annulus and the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. The cranial portion of the left atrium is interposed between the aortic and mitral valves. Anteriorly, the aortic annulus is related to the ventricular septum and right ventricular outflow tract. The His bundle courses beneath the right and noncoronary aortic valve cusps of the membranous ventricular septum. Thus, incision of the aortic annulus or septal myocardium anterior to the right coronary sinus should not interfere with the conduction system.

Pulmonary valve

As with the aortic valve, the pulmonary valve has three cusps, with a midpoint nodule at the free end and lunulae on either side; a sinus is located behind each cusp. Compared with the aortic valve, the pulmonary valve has thinner cusps, no associated coronary arteries, and no continuity with the corresponding (anterior) tricuspid valve leaflet. The term used for each cusp reflects its relationship with the aortic valve, namely right, left, and nonseptal. [11]

Coronary Arteries

The two main coronary arteries are the right and left. However, from a surgical standpoint, the four main arteries are named as the left main, the left anterior descending (LAD), and the left circumflex (LCX) arteries (which are all branches of the left coronary artery) and the right coronary artery (RCA). The RCA and LCXs form a circle around the AV sulci. The LAD and posterior descending arteries form a loop at right angles to this circle; these arteries feed the ventricular septum. The LCX gives off several parallel, obtuse, marginal arteries that supply the posterior left ventricle. The diagonal branches of the LAD artery supply the anterior portion of the left ventricle.

The term dominance is used to refer to the origin of the posterior descending artery (PDA). When the PDA is formed from the terminal branch of the RCA (>85% of the patients), it is termed a right-dominant heart. A left-dominant heart receives its PDA blood supply from a left coronary branch, usually the LCX. This is often referred to as a left posterolateral (LPL) branch.

Left main coronary artery

The left main coronary artery (LCA) originates from the ostium of the left sinus of Valsalva. The LCA, which courses between the left atrial appendage and the pulmonary artery, is typically 1-2 cm in length. When it reaches the left AV groove, the LCA bifurcates into the LAD and the LCX branches. The LCA supplies most of the left atrium, left ventricle, interventricular septum, and AV bundles. The LCA arises from the left aortic sinus and courses between the left auricle and the pulmonary trunk to reach the coronary groove.

Left anterior descending artery

After originating from the left main artery, the LAD artery runs along the anterior interventricular sulcus and supplies the apical portion of both ventricles. The LAD artery is mostly epicardial but can be intramuscular in places. An important identifying characteristic of the LAD artery during angiography is the identification of 4-6 perpendicular septal branches. These branches, approximately 7.5 cm in length, supply the interventricular septum.

The first branch of the LAD artery is termed the ramus intermedius. In fewer than 1% of patients, the LCA is absent and the LAD and LCX arteries originate from the aorta via two separate ostia. As the LAD artery passes along the anterior interventricular groove toward the apex, it turns sharply to anastomose with the posterior interventricular branch of the RCA. As the LAD artery courses anteriorly along the ventricular septum, it sends off diagonal branches to the lateral wall of the left ventricle. Congenital LAD artery variations may include its duplication as two parallel arteries (4% incidence) and length variations (premature or delayed distal termination).

Left circumflex artery

The LCA gives off the LCX artery at a right angle near the base of the left atrial appendage. The LCX artery courses in the coronary groove around the left border of the heart to the posterior surface of the heart to anastomose to the end of the RCA. In the AV groove, the LCX artery lies close to the annulus of the mitral valve. The atrial circumflex artery, the first branch off the LCX artery, supplies the left atrium. The LCX artery gives off an obtuse marginal (OM) branch at the left border of the heart near the base of the left atrial appendage to supply the posterolateral surface of the left ventricle. The color contrast between the yellow-orange OM and the adjacent red-brown myocardium may be the most reliable way to identify this artery intraoperatively. In patients with a left-dominant heart, the LCX artery supplies the PDA. Many variations in the origin and length of the LCX artery are noted. In fewer than 40% of patients, the sinus node artery may originate from the LCX artery.

Right coronary artery

The RCA is a single large artery that courses along the right AV groove. The RCA supplies the right atrium, right ventricle, interventricular septum, and the SA and AV nodes. The RCA arises from the right aortic sinus and courses in the coronary (AV) groove between the right auricle and the right ventricle. In 60% of the patients, the first branch of the RCA is the sinus node artery. As the RCA passes toward the inferior border of the heart, it gives off a right marginal branch that supplies the apex of the heart. After this branching, the RCA turns left to enter the posterior interventricular groove to give off the PDA, which supplies both ventricles.

The AV node artery arises from the "U-turn" of the RCA at the crux (i.e., the junction of the AV septum with the AV groove). At this point, the PDA feeds the septal, right ventricular, and left ventricular branches. The PDA courses over the ventricular septum on the diaphragmatic surface of the heart. Unlike the septal branches off the LAD artery, the septal branches from the RCA typically are short (< 1.5 cm). Terminal branches of the RCA supply the posteromedial papillary muscle of the left ventricle. (The LAD artery supplies the anterolateral papillary muscle of the right ventricle.) Near the apex, the PDA anastomoses with the anterior interventricular branch of the LCA.

Common variations involving RCA anatomy include the following:

-

An RCA originating from the right sinus of Valsalva

-

The sinus node artery originating from the RCA

-

The acute marginal artery crossing the inferior aspect of the right ventricle to supply the diaphragmatic interventricular septum

Coronary Veins

The coronary sinus is a short (approximately 2 cm) and wide venous channel that runs from left to right in the posterior portion of the coronary groove. The opening of the coronary sinus is located between the right AV orifice and the inferior vena cava orifice. The coronary sinus drains all the venous blood from the heart except blood carried from the anterior cardiac veins. The coronary sinus receives outflow from the great cardiac vein on the left and from the middle and small cardiac veins on the right.

The great cardiac vein is the main tributary of the coronary sinus and drains areas of the heart supplied by the LCA. It begins at the apex of the heart, ascends in the anterior interventricular groove with the LAD artery, and enters the left end of the coronary sinus.

The middle and small cardiac veins drain most of the heart supplied by the RCA. The middle cardiac vein begins at the apex, ascends in the posterior interventricular groove with the posterior interventricular artery, and empties into the right side of the coronary sinus. The small cardiac vein runs in the coronary groove along with the marginal branch of the RCA; this vein usually empties into the coronary sinus but may empty directly into the right atrium.

Coronary veins of the right ventricle drain directly into the right atrium; thebesian veins drain into the right ventricle. The left ventricle venous return drains into the coronary sinus located next to the septal portion of the tricuspid valve annulus.

-

Heart, anterior view.

-

Heart, posterior view.

-

Heart, sectioned view.

-

Heart valves, superior view.