Practice Essentials

Anorectal malformations (ARMs) comprise a wide spectrum of anomalies that affect boys and girls and can involve the distal anus and rectum, as well as the urinary and genital tracts. Malformations range from minor and easily treated defects that carry an excellent functional prognosis to complex defects that, despite successful treatment, are often associated with other anomalies and carry a poor functional prognosis.

Throughout the centuries, doctors have seen and attempted to treat infants born with imperforate anus. Few patients were described in the early literature; most are assumed to have died without treatment.

Paulus Aegineta, in the 7th century CE, recorded the earliest account of successful surgery for imperforate anus. He suggested rupturing an obstructing membrane with a finger or knifepoint and then dilating the tract until healing was complete. The Babylonian Talmud, written 2000 years ago, also described what to do for imperforate anus. The reader was advised to place the child in the sun, rub oil on the skin, and then, where the skin appeared transparent, incise it using a barley grain. It is likely that these approaches involved patients with very low-lying ARMs, in which it was possible to reach the meconium and relieve the colonic obstruction.

Anatomy

The Krickenbeck classification (2005) should be used to describe ARMs (see Table 1 below). This is an improvement on the previous Wingspread classification (1984) in that it relies on the specific anatomy of each defect rather than on broad and unhelpful terms such as high, intermediate, and low, which have only a limited bearing on operative planning and prognosis.

Table 1. Krickenbeck Classification of Anorectal Malformations (Open Table in a new window)

| Major Clinical Groups | Rare/Regional Variants |

|---|---|

| Perineal (cutaneous) fistula | Pouch colon |

Rectourethral fistula

|

Rectal atresia/stenosis |

| Rectovesical fistula | Rectovaginal fistula |

| Vestibular fistula | H fistula |

| Cloaca | Others |

| No fistula | |

| Anal stenosis |

The goal of this type of classification system is to define the anatomy of malformations reliably. This is especially important for comparing data from different sites, both nationally and internationally. Making meaningful comparisons is greatly facilitated by using clearly defined anatomic definitions. A 2019 publication by Halleran et al sought to further define the anatomy of rectourethral malformations. [1]

Pathophysiology and Etiology

A sound understanding of the anatomy is helpful to prevent damage to important structures during the surgical repair and to preserve the best potential for fecal and urinary continence.

Anatomic visualization has allowed surgeons to eliminate many previous misconceptions. For instance, the previous classification of these defects into high, intermediate, and low malformations was a misleading oversimplification that did not adequately describe the spectrum of anorectal anomalies.

Improved imaging techniques and a more thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the pelvic structures at birth have refined diagnosis and early treatment. Analysis of large series of patients has allowed better prediction of associated anomalies and functional prognosis.

The surgeon’s primary concerns in correcting these anomalies are to accomplish a successful anatomic reconstruction and to achieve bowel and urinary control. Problems with sexual function and fertility must also be considered.

Early diagnosis, treatment of associated anomalies, and efficient and meticulous surgical repair provide patients the best chance for a good functional outcome.

Some patients experience fecal and occasional urinary incontinence despite excellent anatomic repair. Associated problems (eg, poorly developed sacrum, pelvic musculature, and pelvic nerve roots, as well as tethered cord or myelomeningocele) likely contribute to an inability to achieve continence. For patients with true fecal incontinence, an effective bowel management can provide social cleanliness and effective evacuation of stool. This in turn may improve urinary function, reduce urinary tract infections (UTIs), and improve quality of life. (See Bowel Management.)

Although the etiology remains undefined, a slight genetic predisposition appears to exist.

Epidemiology

ARMs occur in approximately one out of every 3000-5000 births and are slightly more common in males, [2, 3] with a 1% risk that a family will have a second child with an ARM. [4, 5]

A rectourethral fistula is most common in males, and a rectovestibular fistula is most common in females. Having no fistula at all is rare (5% of patients) and is associated with Down syndrome. [6]

In the past, cloaca was considered a rare defect, whereas rectovaginal fistula was commonly reported. In fact, the converse is true: Cloacas are the third most common defect in females, after vestibular and perineal fistulas. A true rectovaginal fistula is rare (< 1% of cases). [7] Incorrect diagnosis in such a case leads to surgical treatment in which only the rectal component is repaired and the patient is left with a a persistent urogenital sinus. [8]

Prognosis

In evaluating the results of treatment of ARMs, patients should not be grouped into the traditional high, intermediate, and low categories from the 1984 Wingspread classification. This classification is flawed in several ways. For instance, within the high group, different ARMs have different treatments and carry different prognoses. Both rectoprostatic fistula and rectobladderneck fistula would be considered high in the Wingspread classification; however, the two malformations are so different that they should not be grouped together. As stated above (see Anatomy), an anatomy-based grouping, such as that provided by the Krickenbeck classification (see Table 1 above), is more clinically valuable. [9]

The functional results after the repair of anorectal anomalies have improved significantly since the advent of the posterior sagittal approach. However, because of inconsistencies in terminology and classification, it has been difficult to compare the results of this approach with those of other methods.

Approximately 75% of all patients with ARMs have voluntary bowel movements. Approximately 50% have soiling episodes. Such episodes are usually related to constipation; when constipation is treated properly, the soiling usually improves. Approximately 40% of all patients have voluntary bowel movements and no soiling. This is the group which would be described as continent. Definitions of continence based on the Rome criteria [10] —one or fewer accidents per week—have increasingly been used to describe continence. This change will make it easier to compare results between various malformations.

At least 30% of patients with ARMs have fecal incontinence and need a bowel management regimen with a daily enema to keep clean (see Bowel Management). Apart from the anorectal anomaly itself, the status of the sacrum, spine, and muscular development greatly affects a patient's chances of having fecal continence. Even with a perfect reconstruction, a patient with complex malformation, a poor sacrum, or an abnormal spinal cord may not achieve continence.

Potential for continence must be evaluated when the child is about 5 years of age.

Patients with less complex malformations (eg, rectoperineal fistula or rectal atresia) have excellent outcomes. Girls with rectovestibular fistulas have very good outcomes, except for a tendency to develop constipation. [11] Approximately 60% of boys with rectourethral fistulae and normal sacra have good outcomes. More than 70% of patients with a short-common-channel cloacal malformation and a normal sacrum can develop continence. Patients with complex malformations (eg, rectobladderneck fistula in boys and long-common-channel cloacal malformations in girls) have poorer outcomes.

The sacrum is a good predictor of outcome in that it correlates with the overall development of the pelvis, including the sphincter muscles and pelvic nerves. Patients with a normal sacrum are much more likely to have fecal continence; those with a hypodeveloped sacrum are much more likely to be incontinent.

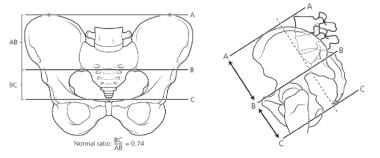

Determination of the sacral ratio allows more objective assessment of the sacrum (see the image below). Patients with a sacral ratio of less than 0.5 are less likely to achieve continence. A hypodeveloped sacrum is also a good predictor of associated spinal and urologic abnormalities. Sacral x-rays should not be taken in the first 3 months of life, because the coccyx is not yet calcified, and obtaining sacral radiographs during this early period may lead to underreading of the sacral ratio.

A method that uses the sacral ratio and other variables to assess the likelihood that a patient with an ARM will have continence is outlined in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Numerical Scoring of Chances of Having Fecal Continence for Patient With Anorectal Malformation (Open Table in a new window)

| Type of ARM | Score |

| Perineal fistula | 1 |

| Anal stenosis | 1 |

| Rectal atresia | 1 |

| Rectovestibular fistula | 1 |

| Rectobulbar fistula | 1 |

| ARM without fistula | 1 |

| Cloaca < 3 cm common channel | 2 |

| Rectoprostatic fistula | 2 |

| Rectovaginal fistula | 2 |

| Rectobladderneck fistula | 3 |

| Cloaca ≥3 cm common channel | 3 |

| Cloacal exstrophy | 3 |

| Spine | Score |

| Normal termination of conus (L1-2) | 1 |

| Normal filum appearance | 1 |

| Abnormally low termination of conus (below L3) | 2 |

| Abnormal fatty thickening of filum | 2 |

| Myelomeningocele | 3 |

| Sacrum | Score |

| Sacral ratio ≥0.7 | 1 |

| Sacral ratio ≥0.4, ≤ 0.69 | 2 |

| Hemisacrum | 2 |

| Sacral hemivertebrae | 2 |

| Presacral mass | 2 |

| Sacral ratio < 4 | 3 |

ARM = anorectal malformation. Individual scores for ARM type, spine, and sacrum are added together. Total scores are interpreted as follows:

|

A child's outcome may be predicted with reasonable accuracy. Patients with good prognoses and those with poor prognoses are easily identifiable. Patients lying between these two categories, however, have proved more difficult to predict, and this issue is being examined in a multicenter study under way at the Pediatric Colorectal and Pelvic Learning Consortium. Parents can be realistically informed of their child's potential for bowel control within the first year of life. This avoids a great deal of frustration later. Establishing the functional prognosis early is vital to avoid raising false expectations in the parents.

Once the diagnosis of the specific defect is established, the functional prognosis may be predicted. The status of the spine, sacrum, and perineal musculature will affect the counseling given to the parents.

If a given defect is one that carries a good prognosis (eg, rectovestibular fistula, rectoperineal fistula, rectal atresia, rectourethral bulbar fistula, or ARM without fistula), the child may be expected to potty train successfully by age 4-5 years. Such children require supervision and treatment to avoid fecal impaction, constipation, and soiling.

Certain defects indicate a poor prognosis, such as a complex cloaca (common channel >3 cm with a short urethra) or a rectobladderneck fistula. Parents should be informed that the child may require a bowel management program to remain clean. The program should be implemented at age 3-5 years (see Bowel Management).

Patients with rectoprostatic fistulas have an almost equal chance of continence or incontinence. Toilet training should be attempted at age 3-5 years; if this is unsuccessful, a bowel management program can be initiated, depending individual home circumstances. Each year, during vacation, potty training should be reattempted; if this is unsuccessful, bowel management should be restarted. As the child grows older and more mature, the likelihood of achieving bowel control improves.

Once it is determined that a daily enema is needed, those patients can continue rectal enemas, if these are well tolerated, or enemas can be given via a Peristeen device or in an antegrade manner via a Malone appendicostomy. [12] The Malone approach is particularly useful for training purposes, in that children can learn to feel the flush and hold the flush in, all while sitting on the toilet. They can thereby improve their pelvic floor control. Pelvic floor physiotherapy is a very helpful adjunct to this conditioning.

Urinary incontinence occurs in boys with ARMs only when they have an extremely defective or absent sacrum or an abnormal spine or when the basic principles of surgical repair are not followed and important nerves to the bladder neck are damaged during the operation. The vast majority of boys have urinary control. This is also true for girls, with the exception of the group with complex cloaca, who not infrequently need clean intermittent catheterization (CIC; see Cloacal Malformations).

Careful, regular observation is necessary in these patients for accurate reassessment of the prognosis and for avoidance of problems that can dramatically affect the ultimate functional results. In addition, this group also requires close follow-up of the kidneys to help mitigate the development of renal impairment by actively treating common problems (eg, recurrent UTIs and reflux) and by ensuring good bladder emptying. If the original anal surgery was not done properly and the patient has an anal mislocation, rectal prolapse, rectal stricture, or retained remnant of the original fistula (ROOF), a reoperation may be indicated to improve the anatomy and help the patient realize his or her bowel control potential. [13]

-

Newborn boy with imperforate anus.

-

Newborn girl with imperforate anus.

-

Crossfire radiograph in which air column in distal rectum can be observed close to perineal skin.

-

Perineum of newborn with cloaca. Note single perineal orifice.

-

Hemisacrum with presacral mass.

-

Absent lumbosacral vertebrae (severe vertebral anomaly).

-

Tethered cord.

-

Calculation of sacral ratio.

-

Ultrasonography demonstrates hydronephrosis in newborn with imperforate anus.

-

Cystography of neurogenic bladder.

-

Multicystic kidney.

-

Mercaptotriglycylglycine (MAG-3) renal scan in patient with multicystic kidney and imperforate anus.

-

Vesicoureteral reflux.

-

Distal colostography in patient with imperforate anus and rectourethral fistula, in this case at prostatic level.

-

Newborn with imperforate anus and rectoperineal fistula.

-

Newborn with imperforate anus and bucket-handle malformation (usually associated with rectoperineal fistula).

-

Diagram of imperforate anus and rectourethral fistula.

-

Augmented-pressure distal colostography demonstrating rectourethral fistula only when adequate pressure is used. Note flat rectum on left, which represents compression of distal rectum in funnel-like sphincteric mechanism.

-

Diagram of imperforate anus and rectovestibular fistula.

-

Imperforate anus and rectovestibular fistula in newborn.

-

Recommended colostomy with divided stomas, with proximal stoma in descending colon.

-

Operative view of posterior sagittal anoplasty in newborn with rectoperineal fistula.

-

Positioning for posterior sagittal approach.

-

Posterior sagittal incision.

-

Electrical stimulator probe used to show sphincteric contractions.

-

Posterior sagittal incision showing parasagittal fibers.

-

Schematic diagram of anatomy and repair of rectourethral anorectal malformation.

-

Posterior sagittal repair of rectovestibular fistula.

-

Closure of posterior sagittal incision.

-

Anorectal anomalies (not including cloaca) that may be noted in newborn girls, as compared with normal anus that is located slightly more anteriorly than usual. Image from Marc Levitt, MD.

-

Turnbull loop colostomy: diverting loop that functions as end stoma but affords access to distal segment. Image from Marc Levitt, MD.

-

Creation of loop colostomy. Image from Marc Levitt, MD.