Practice Essentials

The embryology of the umbilicus and the developmental basis for surgical abnormalities has been well described for more than 100 years. Umbilical hernias, abdominal wall defects, umbilical polyps and drainage, [1] and omphalomesenteric remnants are well described.

A stark contrast is observed between the physiologic importance of the umbilicus during development and its importance after birth. During development, the umbilicus functions as a channel that allows blood flow between the placenta and fetus. It also serves an important role in the development of the intestine and the urinary system. After birth, once the umbilical cord falls off, no evidence of these connections should be present.

Nevertheless, umbilical disorders are frequently encountered in pediatric surgery. [2] An understanding of the anatomy and embryology of the abdominal wall and umbilicus is important for identifying and properly treating these conditions. [3]

Patients with umbilical disorders present with drainage, a mass, or both. Most umbilical disorders result from failure of normal embryologic or physiologic processes. Unusual umbilical anatomy, such as a single umbilical artery or abnormal position of the umbilicus, may be associated with other congenital anomalies or syndromes. Omphalocele and gastroschisis, which are common abdominal wall defects associated with the umbilicus, are discussed further elsewhere (see Pediatric Omphalocele and Gastroschisis).

Masses of the umbilicus may be related to lesions of the skin, embryologic remnants, or an umbilical hernia. Masses associated with the skin include dermoid cysts, hemangiomas, and inclusion cysts. Umbilical drainage is associated with granulomas and embryologic remnants. The following should be noted:

-

Delayed separation of the umbilical cord - The umbilical cord usually separates from the umbilicus 1-8 weeks postnatally; topical antimicrobials are usually applied after delivery, followed by isopropyl alcohol until cord separation; delayed separation may signify an underlying immune disorder

-

Umbilical granuloma - Granulation tissue may persist at the base of the umbilicus after cord separation; the tissue is composed of fibroblasts and capillaries and can grow to more than 1 cm; umbilical granulomas must be differentiated from umbilical polyps and from granulomas secondary to a patent urachus, both of which do not respond to silver nitrate cauterization

-

Umbilical infections - Patients with omphalitis may present with purulent umbilical discharge or periumbilical cellulitis; although infections may be associated with retained umbilical cord or ectopic tissue, they were often, in the past, related to poor hygiene; current aseptic practices and the routine use of antimicrobials on the umbilical cord have reduced the incidence to less than 1%; cellulitis may become severe and rapidly progess within hours to necrotizing fasciitis and generalized sepsis, and thus, prompt attention and treatment are critical

-

Omphalomesenteric remnants - Persistence of all or portions of the omphalomesenteric duct can result in fistulas, sinus tracts, cysts, congenital bands, and mucosal remnants; patients with mucosal remnants can present with an umbilical polyp or an umbilical cyst

-

Urachal remnants - The developing bladder remains connected to the allantois through the urachus, and remnants of this connection include a patent urachus, urachal sinus, and urachal cyst; umbilical polyps and granulomas can also be observed in association with a urachal remnant

-

Umbilical hernias - These result when persistence of a patent umbilical ring occurs; some umbilical hernias close spontaneously, but many require surgical repair [4]

Methods of management in some disorders, such as treating umbilical granulomas with silver nitrate, have changed little over the last century. In the early 1900s, umbilical hernia repair was a challenging procedure. Spontaneous closure of these hernias and preservation of the appearance of the natural umbilicus were recognized. Today, umbilical hernia repair is one of the most common procedures performed by pediatric surgeons.

Anatomy

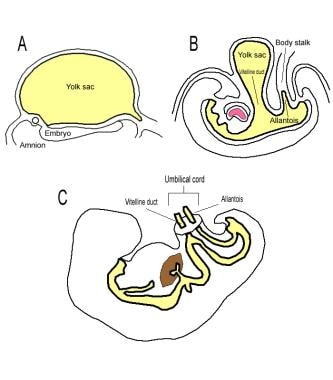

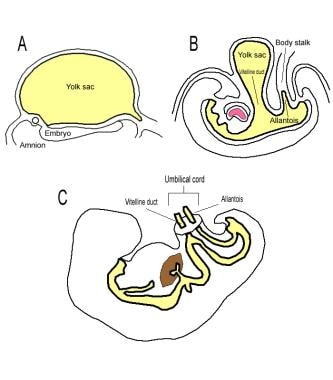

During development, the embryonic disk is in contact with the yolk sac anteriorly (see the image below). As the embryo grows and differential growth of tissues leads to the folding appearance of the embryo, the ventral attachment of the yolk sac narrows. The intracoelomic portion of the yolk sac becomes the primitive alimentary canal and attaches to the extracoelomic portion through the vitelline duct. The allantois buds from the hindgut and grows into the body stalk. The yolk stalk and the body stalk eventually fuse to become the umbilical cord.

Cartoon illustrating the developing umbilical cord. (A) Embryonic disk: At this stage, the ventral surface of the fetus is in contact with the yolk sac. (B) The yolk sac narrows as the fetus grows and folds. The intracoelomic yolk sac forms the intestine and communicates with the extracoelomic yolk sac through the vitelline duct. The vitelline duct is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct and the yolk stalk. The allantois has begun to grow into the body stalk. (C) The yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord.

Cartoon illustrating the developing umbilical cord. (A) Embryonic disk: At this stage, the ventral surface of the fetus is in contact with the yolk sac. (B) The yolk sac narrows as the fetus grows and folds. The intracoelomic yolk sac forms the intestine and communicates with the extracoelomic yolk sac through the vitelline duct. The vitelline duct is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct and the yolk stalk. The allantois has begun to grow into the body stalk. (C) The yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord.

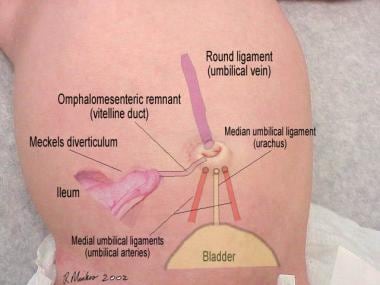

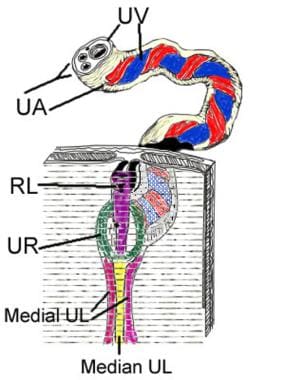

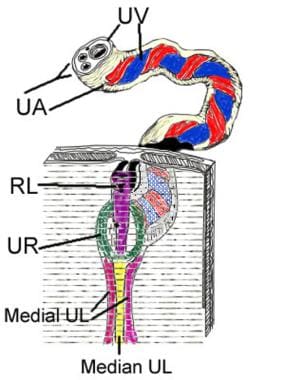

As the abdominal wall forms, the umbilical ring is narrowed. The vitelline and umbilical vessels, vitelline duct, and allantois should be absent in the umbilicus at term. Residual tissue leads to remnants that require surgical intervention. During exploration for a sinus or fistula, all structures, including the round ligament, median, and medial umbilical ligaments, must be identified (see the images below). An omphalomesenteric or urachal sinus or fistula must be dissected back to its origin in the ileum or bladder, respectively.

Umbilical region viewed from the posterior surface of the abdominal wall of an infant with the umbilical cord attached. UA: Umbilical artery; UV: Umbilical vein; RL: Round ligament (obliterated umbilical vein); UR: Umbilical ring; UL: Umbilical ligament; medial (obliterated umbilical arteries); median (obliterated urachus). Note fascial covering of surface and umbilical ring.

Umbilical region viewed from the posterior surface of the abdominal wall of an infant with the umbilical cord attached. UA: Umbilical artery; UV: Umbilical vein; RL: Round ligament (obliterated umbilical vein); UR: Umbilical ring; UL: Umbilical ligament; medial (obliterated umbilical arteries); median (obliterated urachus). Note fascial covering of surface and umbilical ring.

Pathophysiology

Failure of the normal obliterative processes of the vitelline duct and the urachus leads to abnormal communications or cysts. Retention of components of the umbilical cord can also produce a mass or drainage.

A patent umbilical ring at birth is responsible for most umbilical hernias. The umbilical opening is usually inferiorly reinforced by the attachments of the median umbilical ligament (the obliterated urachus) and the paired medial umbilical ligaments (the obliterated umbilical arteries) and is more weakly superiorly reinforced by the round ligament (the obliterated umbilical vein). (See the image below.)

Umbilical region viewed from the posterior surface of the abdominal wall of an infant with the umbilical cord attached. UA: Umbilical artery; UV: Umbilical vein; RL: Round ligament (obliterated umbilical vein); UR: Umbilical ring; UL: Umbilical ligament; medial (obliterated umbilical arteries); median (obliterated urachus). Note fascial covering of surface and umbilical ring.

Umbilical region viewed from the posterior surface of the abdominal wall of an infant with the umbilical cord attached. UA: Umbilical artery; UV: Umbilical vein; RL: Round ligament (obliterated umbilical vein); UR: Umbilical ring; UL: Umbilical ligament; medial (obliterated umbilical arteries); median (obliterated urachus). Note fascial covering of surface and umbilical ring.

Richet fascia, derived from the transversalis fascia, covers the ring. The peritoneum covers the innermost portion of the ring. Variability in the attachment of the ligaments and the covering by Richet fascia may predispose some children to developing umbilical hernias (see the image below). Variations in the covering of the umbilical ring by umbilical fascia include the following:

-

Umbilical fascia completely covers the ring (36%)

-

Umbilical fascia is present but does not cover the ring (4%), or fascia is absent (16%)

-

Umbilical fascia covers only the superior portion of the ring (38%)

-

Umbilical fascia covers only the inferior portion of the ring (6%)

Variations in the umbilical ring structure. (A) Usual configuration of the round ligament and urachus. (B) Less common configuration that can result in weakness at the umbilical ring.

Variations in the umbilical ring structure. (A) Usual configuration of the round ligament and urachus. (B) Less common configuration that can result in weakness at the umbilical ring.

Nevertheless, many children undergo spontaneous closure in the first few years of life. The pressure exerted on the umbilical skin, even when only a small umbilical defect is present, can result in marked stretching of the skin and a proboscis appearance.

Etiology

The development of the anterior abdominal wall depends on differential growth of embryonic tissues (see the image below). As the embryo grows, the yolk sac is divided into an intracoelomic portion and an extracoelomic portion. The intracoelomic portion becomes the primitive alimentary canal and communicates with the extracoelomic portion through the vitelline duct, also known as the omphalomesenteric duct. This communication is lost at 5-7 weeks' gestation. Persistence of part or all of this connection results in omphalomesenteric anomalies.

Cartoon illustrating the developing umbilical cord. (A) Embryonic disk: At this stage, the ventral surface of the fetus is in contact with the yolk sac. (B) The yolk sac narrows as the fetus grows and folds. The intracoelomic yolk sac forms the intestine and communicates with the extracoelomic yolk sac through the vitelline duct. The vitelline duct is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct and the yolk stalk. The allantois has begun to grow into the body stalk. (C) The yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord.

Cartoon illustrating the developing umbilical cord. (A) Embryonic disk: At this stage, the ventral surface of the fetus is in contact with the yolk sac. (B) The yolk sac narrows as the fetus grows and folds. The intracoelomic yolk sac forms the intestine and communicates with the extracoelomic yolk sac through the vitelline duct. The vitelline duct is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct and the yolk stalk. The allantois has begun to grow into the body stalk. (C) The yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord.

In the third week, the yolk sac develops a diverticulum, the allantois, which grows into the body stalk. As the distal hindgut and the urogenital sinus separate, the developing bladder remains connected to the allantois through a connection called the urachus. [5] Persistence of the urachus leads to urachal remnants. Subsequently, the yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord. Development of the abdominal wall narrows the umbilical ring, which should close before birth. Persistence of the ring results in an umbilical hernia.

Epidemiology

The frequencies of the many different umbilical disorders vary. Umbilical infections are now identified in fewer than 1% of hospitalized newborns.

Umbilical hernias are commonly identified in early infancy; however, most spontaneously close. No sex predilection is noted. The incidence at age 1 year ranges from 2-15%. Incidence is increased in infants who are black and in infants with low birth weight, Down syndrome, trisomy 13, trisomy 18, or Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

Prognosis

The outcome for infants and children with umbilical hernias and embryologic remnants is generally excellent. In most cases, no long-term problems occur. However, Rosen et al suggested that umbilical hernia repair may increase the incidence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in childhood. [6]

In contrast, in most series, omphalitis leading to necrotizing fasciitis is associated with a high mortality, possibly as high as 80%. Necrotizing fasciitis can also lead to portal venous thrombosis and portal hypertension.

-

Cartoon illustrating the developing umbilical cord. (A) Embryonic disk: At this stage, the ventral surface of the fetus is in contact with the yolk sac. (B) The yolk sac narrows as the fetus grows and folds. The intracoelomic yolk sac forms the intestine and communicates with the extracoelomic yolk sac through the vitelline duct. The vitelline duct is also referred to as the omphalomesenteric duct and the yolk stalk. The allantois has begun to grow into the body stalk. (C) The yolk and body stalks fuse to become the umbilical cord.

-

Umbilical region viewed from the posterior surface of the abdominal wall of an infant with the umbilical cord attached. UA: Umbilical artery; UV: Umbilical vein; RL: Round ligament (obliterated umbilical vein); UR: Umbilical ring; UL: Umbilical ligament; medial (obliterated umbilical arteries); median (obliterated urachus). Note fascial covering of surface and umbilical ring.

-

Variations in the umbilical ring structure. (A) Usual configuration of the round ligament and urachus. (B) Less common configuration that can result in weakness at the umbilical ring.

-

Preoperative photograph demonstrating umbilical hernia with redundant skin.

-

Omphalomesenteric duct remnants. (A) Meckel diverticulum. Note feeding vessel. (B) Meckel diverticulum attached to posterior surface of anterior abdominal wall by a fibrous cord. (C) Fibrous cord attaching ileum to abdominal wall. (D) Intestinal-umbilical fistula. Intestinal mucosa extends to skin surface. (E) Omphalomesenteric cyst arising in a fibrous cord. The cyst may contain intestinal or gastric mucosa. (F) Umbilical sinus ending in a fibrous cord attaching to the ileum. (G, H) Omphalomesenteric cyst and sinus without intestinal attachments.

-

Photograph of newborn with intestinal prolapse through a patent omphalomesenteric duct. Both the proximal and distal limbs of the intestine have prolapsed. The umbilicus was explored, the bowel was easily reduced, and the patent duct was excised. The child was discharged from the hospital 2 days later.

-

Anatomic relationship between the umbilicus and its embryologic attachments.

-

Laparoscopic removal of urachal cyst (U). L indicates the left medial umbilical ligament. R indicates the right medial umbilical remnant. B indicates the bladder. The distal attachment to the bladder is being grasped.

-

Laparoscopic removal of urachal cyst. View is from left lower abdomen port. The umbilicus is on the right and the bladder on the left. The attachments or the urachal cyst to the bladder and the umbilicus have been clipped (not shown) and divided. Note the convergence of the right and left medial umbilical ligaments as they approach the umbilical ring on the right.

-

Photograph of laparoscopically removed urachal cyst and its attachments.

-

Urachal sinus with purulent drainage in midline below the umbilicus (black arrow). A laparoscope was placed in the supraumbilical crease (red arrow) for mobilization of the internal portion of the urachal remnant as depicted in the next image.

-

Urachal cyst mobilized by the laparoscopic approach. Arrow demonstrates sinus communication through abdominal wall and skin 3 cm inferior to the umbilicus. See next image.

-

External mobilization of urachal sinus through abdominal wall incision 3 cm inferior to umbilicus. Patient presented with recurrent drainage and infection from sinus. The internal portion was mobilized laparoscopically. See previous image.

-

Neoumbilicus following umbilicoplasty.

-

Upper gastrointestinal contrast study showing incidental umbilical hernia in an infant. Red line outlines the umbilical hernia. The arrow shows contrast flowing into the intestine within the umbilical hernia. The umbilical hernia was easily reducible and no intervention based on this study was performed.

-

Laparoscopic view of urachal fistula, which extends from umbilicus above to bladder below. Image courtesy of Eugene S Kim, MD.

-

Laparoscopic view of remnant fibrous band of omphalomesenteric duct, which extends from umbilicus to terminal ileum below. Image courtesy of Eugene S Kim, MD.