Practice Essentials

Pediatric ostomies include any surgically created opening between a hollow organ (eg, the small or large intestine) and the skin connected either directly (stoma) or with the use of a tube.

Colostomies were used in the late 1800s to treat intestinal obstruction. Some of the earliest survivors were children with an imperforate anus. Creation of an intestinal stoma was considered a drastic procedure and was avoided because of the high incidence of complications and mortality. With improvements in surgical technique and practice, the need for stomas increased as more children with formerly fatal conditions survived.

Since the early success with colostomy formation in the 1800s, the use and management of gastrointestinal (GI) stomas in children have evolved. Improved surgical techniques, better understanding of the physiologic and psychological consequences of intestinal stomas, and advances in stoma care have contributed to more rational use of ostomies by pediatric surgeons and a wider acceptance in the medical and lay communities (though the frequency of intestinal stomas in the pediatric population is difficult to determine).

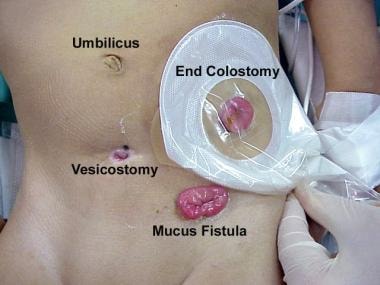

Nevertheless, treating a child with multiple abdominal stomas can be intimidating and challenging (see the image below), especially when the anatomy is not clear and the fluid and electrolyte abnormalities are difficult to control.

Multiple stomas in abdomen of 3-year-old child who underwent surgery as infant for high imperforate anus. Divided colostomy was performed to divert stool. Other end was brought out through skin (mucous fistula) to allow evacuation of mucus and gas. Vesicostomy was performed because of neurogenic bladder.

Multiple stomas in abdomen of 3-year-old child who underwent surgery as infant for high imperforate anus. Divided colostomy was performed to divert stool. Other end was brought out through skin (mucous fistula) to allow evacuation of mucus and gas. Vesicostomy was performed because of neurogenic bladder.

Although great advances have been made with regard to stoma formation and management, both early and late complications are common. Fortunately, most pediatric stomas are temporary, and many of the complications associated with intestinal stomas are eliminated when the stoma is closed. Understanding enterostomal construction and physiology is essential for providing these children with optimal care.

Etiology

Several situations necessitate formation of a stoma or placement of a tube within the bowel. Small-bowel stomas are used for patients with intestinal perforation or ischemia when an anastomosis is considered unsafe. A proximal ileostomy is often used to protect a more distal anastomosis or after restorative proctocolectomy for familial polyposis or ulcerative colitis.

Similarly, a colostomy can used both before and after a pull-through procedure for imperforate anus or Hirschsprung disease, though many surgeons are now performing primary pull-through procedures without colostomy for both of these conditions. Tube cecostomy or Malone appendicocecostomy have been used for antegrade bowel irrigation in children with intractable constipation and various medical conditions. [1, 2]

Children with severe perineal burns or trauma (see the image below) often require a temporary colostomy to allow the injury to heal.

Severe injury to perineum and anal sphincter (caused by lawnmower) in 9-year-old boy. Diverting colostomy was performed. Several weeks later, skin graft was placed over defect. After reconstruction of anal sphincter, colostomy was reversed.

Severe injury to perineum and anal sphincter (caused by lawnmower) in 9-year-old boy. Diverting colostomy was performed. Several weeks later, skin graft was placed over defect. After reconstruction of anal sphincter, colostomy was reversed.

Neonates with the following conditions may require a stoma:

-

Meconium ileus

-

Complex hindgut anomalies

-

Trauma [4]

Children and adolescents with the following conditions may require a stoma:

-

Trauma

Prognosis

Outcome for pediatric patients with intestinal stomas depends on the underlying condition. Fortunately, most stomas in infants and children are reversible. Reestablishing bowel continuity depends on factors such as the underlying disease, the general medical condition of the child, and the presence of stoma-related complications. Understanding the anatomy prior to stoma closure is crucial. In most instances, a preoperative distal contrast-enhanced study should be performed.

In general, the prognosis for patients with intestinal stomas is good. The exception is in patients with stomas and short-bowel syndrome. In such cases, reversal of the stoma should be attempted as soon as possible in order to maximize the absorptive capacity of the intestines. However, in many cases of short-bowel syndrome, ostomy reversal is not possible because of other associated comorbid conditions. The most common causes of short-bowel syndrome in North America are necrotizing enterocolitis, abdominal-wall defects, atresia, and midgut volvulus.

In a retrospective cohort study intended to compare clinical outcomes of loop and divided colostomies in patients with anorectal malformations, Oda et al found that the former, because of the higher incidence of prolapse, carried a higher total complication rate than the latter but that the rates of other complications (eg, megarectum and urinary tract infection) did not differ significantly between the two stoma types. [5]

A retrospective study by Vriesman et al assessed the number and type of complications and subsequent reoperations after ostomy formation in children who underwent ileostomy (n = 129) or colostomy (n = 61). [6] Of the 190 patients, 62 (32.6%) had motility disorders, including functional constipation (n = 40), Hirschsprung disease (n = 18) and pediatric intestinal pseudo-obstruction (n = 4). The total prevalence of complications was 73.2%. Children with motility problems had a higher complication rate (88.7% vs 65.5%) than those without such problems, as well as a higher percentage of high-grade complications (61.8% vs 31.0%).

-

Multiple stomas in abdomen of 3-year-old child who underwent surgery as infant for high imperforate anus. Divided colostomy was performed to divert stool. Other end was brought out through skin (mucous fistula) to allow evacuation of mucus and gas. Vesicostomy was performed because of neurogenic bladder.

-

Severe injury to perineum and anal sphincter (caused by lawnmower) in 9-year-old boy. Diverting colostomy was performed. Several weeks later, skin graft was placed over defect. After reconstruction of anal sphincter, colostomy was reversed.

-

Diagrams illustrate pediatric stomas. (A) End stoma (inset shows everting maturation); (B) double-barrel stoma, with end stoma and mucous fistula divided and brought through same incision (inset shows closed mucous fistula sutured to abdominal wall); (C) loop stoma; (D) decompressing blowhole stoma; (E) Bishop-Koop stoma; and (F) Santulli stoma

-

Divided end ileostomy and ileal mucous fistula. Ileostomy is brought out through separate skin incision.

-

End ileostomy with closed distal limb (also known as Hartmann pouch).

-

End ileostomy with closed distal intestine after multiple resections. Segment without function is left in situ, and stoma is used for decompression.

-

End-to-side anastomosis created in infant with complicated meconium ileus, with distal stoma used for irrigation (also known as Bishop-Koop ileostomy).

-

Potential sites for neonate and infant stomas.

-

Potential sites for stomas in older child or adolescent. Ideally, stoma is brought through rectus muscle in position that allows placement of stoma appliance.

-

Stoma brought directly through umbilicus.

-

Stoma matured through separate inferior umbilical incision.

-

Appearance of violaceous rash commonly due to Candida albicans. String coming out of distal stoma was passed through distal stricture and out of anus.

-

Skin irritation, stoma retraction, and wound infection after placement of stoma through laparotomy incision.

-

Prolapse of loop colostomy. Both proximal and distal limbs have prolapsed. This may or may not cause intestinal obstruction.

-

Wound infection and postoperative sepsis may also occur after formation of stoma. Note redness of skin at laparotomy incision site and evidence of soft-tissue abdominal-wall infection.

-

Stoma in 8-month-old infant.