Overview

Chest wall deformities represent a group of congenital diseases that affect the geometry, integrity, and function of the thoracic cage and viscera. These disorders can exist in isolation or as part of a genetic syndrome. [1] Affected individuals can be asymptomatic or experience respiratory, cardiovascular, and psychosocial impairments.

Pectus excavatum, also known as funnel chest or trichterbrust, is by far the most common chest wall deformity, occurring in 1 of every 400 White male births. [2] Pectus carinatum, the next most common chest wall deformity, is five times less common than pectus excavatum. [3] See the images below.

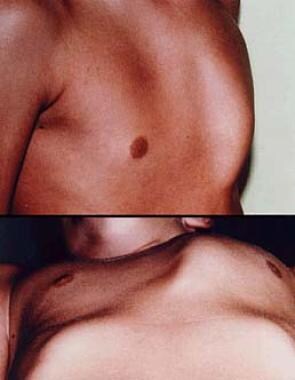

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

For more than half a century, the traditional method of repair for pectus excavatum was the modified Ravitch repair. In 1998, a minimally invasive method of repair, the Nuss procedure, was introduced. This article reviews the available literature regarding the pathophysiology of pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum, and the efficacy and safety of both approaches.

Pectus Excavatum

Embryology and etiology

Several theories explain the cause of pectus excavatum; however, the etiology remains obscure. Some authors believe that pectus excavatum may be due to an overgrowth of costal cartilage, which displaces the sternum posteriorly. Abnormalities of the diaphragm, rickets, or elevated intrauterine pressure are also theorized to cause posterior displacement of the sternum. [4, 5, 6] Reports of pectus excavatum occurring with diaphragmatic agenesis and congenital diaphragmatic hernia may support this theory. [4, 5, 7] Scoliosis is reported in 21% of patients with pectus excavatum, and 11% of patients with pectus excavatum have a family history of scoliosis. [8]

The coexistence of pectus excavatum with other musculoskeletal disorders, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, suggests that an abnormality of connective tissue may be involved. In addition, 40% of patients with pectus excavatum have a familial history, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition. [9]

Clinical presentation and evaluation

The appearance of pectus excavatum can range from a mild, shallow sternal indentation to one in which the sternum almost touches the vertebral bodies. The appearance of the defect is the result of two factors: (1) the degree of posterior angulation of the sternum and (2) the angulation of the costal cartilages as they meet the sternum. Asymmetry in the angulation of the ribs and costal cartilages can result in an unbalanced angulation of the sternum, requiring more complex operative techniques. These defects become more challenging for the surgeon to manage. [10]

Pectus excavatum is present at birth or arises shortly thereafter. It is often progressive, and the depth increases as the child grows. [11] Pectus excavatum is more common in males than in females, with a male-to-female ratio of 6:1. Two percent of patients with pectus excavatum have additional congenital cardiac anomalies. Among individuals with marfanoid body habitus and additional clinical criteria associated with a connective tissue disorder, the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome should be considered. This population experiences significant morbidity and mortality associated with aortic root dilatation, as well as aortic dissection and rupture. [12]

The appropriate diagnostic evaluation can assist in appropriate surveillance and, in some instances, facilitate coordination of pectus repair with concomitant cardiac procedures. [13] However, the authors of this topic have found that pectus repair in the setting of open cardiac surgery is uncommon. In patients who require extracardiac conduits, pectus excavatum repair may be considered to avoid external compression of the conduit. Some patients with pectus excavatum may need lung transplantation in their adulthood due to another diagnosis. This is best managed with bilateral thoracotomy and simultaneous pectus repair to achieve maximal lung expansion, rather than via a clamshell incision.

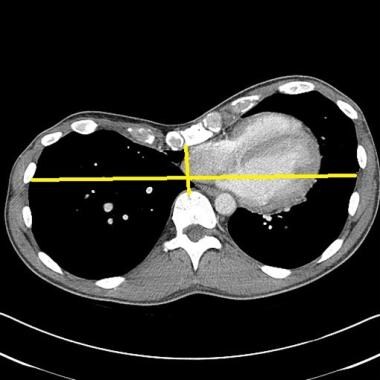

Several objective methods have been developed to quantitate the severity of pectus excavatum. The most commonly used method is that of Haller et al [14] ; this method uses a ratio of the transverse distance to the anteroposterior (AP) distance derived from imaging. A normal Haller index in children ranges from 1.9 to 2.7. [15] The higher the Haller index is indicates the degree of sternal depression; a Haller index of 3.5 is considered a severe pectus. Objectively measuring the severity of the pectus is imperative among patients that are symptomatic and require repair. This index is important from the standpoint of insurance coverage as it is an objective measure of the chest wall deformity.

Standard AP and lateral chest x-rays can be utilized to measure a pectus defect. However, appropriate identification and measurement of the bony and cartilaginous chest wall can prove difficult on plain films, particularly among patients with significant asymmetry. Cross-sectional imaging assists in measuring the defect accurately.

Pectus patients are typically young children and young adults. To reduce radiation exposure, some centers utilize low dose non-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scanning during full inspiration. [15] In a single-center prospective study, Hehman and colleagues found that ultra-low dose chest CT scanning was effective in measuring the indices among patients with pectus. [16] It is important to note that, based on regional variation, low dose CT scans are only reimbursed when performed for highly specific clinical circumstances.

This image depicts a high Haller index pectus excavatum causing displacement of heart into left chest. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

This image depicts a high Haller index pectus excavatum causing displacement of heart into left chest. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

This image demonstrates a high Haller index pectus excavatum that is compressing the right atrium and inferior vena cava. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

This image demonstrates a high Haller index pectus excavatum that is compressing the right atrium and inferior vena cava. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

Evaluation for pectus is based on the individual patient. Testing most often includes a battery of examinations to evaluate the cardiopulmonary consequences of the deformity and includes electrocardiograms (ECG), transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), stress testing, and pulmonary function testing (PFTs). Among patients with a personal or family history that is consistent with a connective tissue disorder, consultation with a genetic counselor is recommended.

Pectus excavatum has no discernible physiologic effect on infants or children. Some children have pain around the sternum or costal cartilage, especially after vigorous exercise. Other children have palpitations that might be related to mitral valve prolapse, which commonly occurs with pectus excavatum. A flow murmur may also be detectable in some patients. This flow murmur is related to the close proximity of the sternum to the pulmonary artery, resulting in transmission of a systolic ejection murmur. [17]

Adults with severe depression may experience chest pain, shortness of breath, and palpitations that worsen with postural changes. In addition, adults may report exercise intolerance and recall difficulty keeping up with their peers during childhood. Gonzalez and colleagues reported that adults are more symptomatic, have reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) / forced vital capacity (FVC) ratios on PFTs as well as decreased exercise capacity on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). [18]

Further studies are needed to evaluate possible age-related decline among pectus patients, as this would assist in decision making among young patients, their caregivers, and providers regarding the appropriate timing of surgical referrals.

The impact of pectus excavatum on the cardiopulmonary system continues to be debated due to the contradictory results of studies. Patients report shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, and fatigue. However, PFTs are often normal and fail to correlate with symptoms. [19] It is possible PFTs do not accurately measure the respiratory deficits experienced in this population. Many clinicians advise to only reserving pulmonary testing for those with severe deformities. [20] However, O’Keefe and colleagues documented modest improvements in PFTs 3 months after bar removal. [21]

A meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of pectus excavatum repair on pulmonary function revealed no statistically significant improvement. No difference in pulmonary function was observed between surgical approaches. [22] However, a meta-analysis by Chen and colleagues identified improvement in pulmonary function after the correction of pectus. [23] Asthma is sometimes noted in children with both pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum, but pectus excavatum does not seem to affect the clinical course of asthma in patients.

Small studies evaluating the efficacy of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) before and after pectus repair, in children and adults, have documented improvements in right heart chamber dimensions. [24] Although there are limited data on cardiac arrhythmias and pectus excavatum, case reports exist of atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias in pectus patients that resolve after operative management. [25, 26] The mechanism of pectus-induced arrhythmias requires further evaluation: It is unclear if arrhythmias in this population are related to focal compressive cardiomyopathy.

In a meta-analysis that studied the impact of pectus excavatum on the cardiovascular system, Malek et al revealed a significant improvement in cardiovascular function following surgical repair of pectus excavatum. Specifically, a 6-13% postoperative improvement in the cardiac output, stroke volume, and pulse oximetry was observed. [27] The investigators suggested that poor results reported in past studies could have been related to deconditioning following surgical repair or submaximal exercise testing. Patients with pectus excavatum who underwent incremental exercise testing prior to the repair reached their ventilatory threshold at 39% of the predicted maximum rate of oxygen consumption attainable during physical exertion (VO2 max predicted), which improved postoperatively to 50% of VO2 max predicted. [28] More recently, Obermeyer and colleagues identified consistent improvements in cardiopulmonary exercise testing and right ventricular stroke volumes among adults with pectus that underwent surgery. [29]

Surgical Repair of Pectus Excavatum

Indications for surgery

Although discerning a specific physiologic consequence of pectus excavatum is difficult, several surgical indications are noted: severe pectus defined as a Haller index above 3.5, physically symptomatic pectus, and abnormal cardiopulmonary testing. Among patients with severe pectus, it is also imperative to address psychosocial distress. [30] The sunken appearance of the chest wall has been associated with poor self-image in children, especially as they approach adolescence; the major indication is currently psychosocial. [31] Improvement of the appearance of the chest wall after the repair improves socialization. [31] In competitive athletes, in whom a slight decrease in exercise tolerance may impair their performance, surgeons may also choose to repair the pectus excavatum. A previous failed repair is also an important indication for surgery.

When performed in the setting of cardiac surgery, a single-stage repair of pectus excavatum has been reported using a sternal flap based on the internal thoracic arteries, followed by repair of the intracardiac defect and a traditional Ravitch repair. [32] Alternative approaches have included the Ravitch repair followed by a left parasternal approach to the cardiac defect. [33] A left thoracotomy approach has also been described for patients with unrepaired pectus excavatum and mitral or aortic valvular disease. [34] In the absence of a specific indication to make more room in the chest for a cardiac repair, the authors of this chapter elect to repair a pectus excavatum subsequent to the intracardiac repair.

Surgical repair

Meyer performed the first surgical repair of pectus excavatum in 1911, [35] followed by Sauerbruch in 1913. [36] In 1949, Ravitch reported a technique that formed the basis of modern pectus excavatum surgery [37] : Through a midline incision over the sternal depression, all deformed cartilage from the perichondrium was excised; the sternum was mobilized by division of the xiphoid from the sternum; and a transverse sternal osteotomy was performed. The sternum was displaced anteriorly and held into position using wires. [37]

In 1958, Welch modified the above procedure by preserving the perichondrial sheaths of the costal cartilages to allow for regrowth. [38] He preserved the intercostal bundles and fixed the sternum anteriorly with silk suture. Other surgeons further modified this approach by adding a metal strut to ensure stability of the sternum in the new raised position. [39, 40]

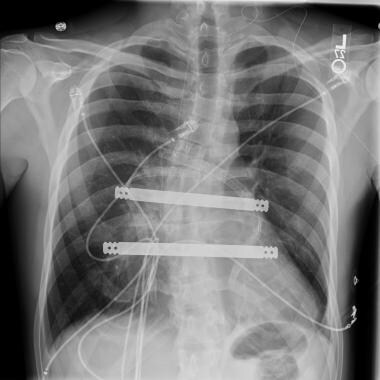

An anteroposterior radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

An anteroposterior radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

A lateral radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

A lateral radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

Davis and Weinstein presented a series of 69 consecutive patients with the pectus deformity who underwent a modified Ravitch repair. [41] Their modification included developing a generous subcutaneous flap over the muscle fascia, thus greatly limiting the skin incision for both pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum correction procedures. A median of four sets of costal cartilage were removed in both subgroups. Then, a posterior sternal table osteotomy was performed, with placement of a triangular wedge of rib bone harvested from a lateral rib for stabilization. Asymmetry was dealt with by adjusting the angle of the posterior osteotomy. Good-to-excellent results were reported in 81.3% of the patients. No deaths or significant intraoperative morbidities occurred, although postdischarge seromas developed in five patients (7.2%) that required aspiration. [41]

Davis and Weinstein concluded that the modified Ravitch procedure remains a safe and effective approach to the repair of the pectus deformity in all of its presentations. Because the technique rarely uses a metal strut, a second procedure for strut removal is not necessary. [41]

Fonkalsrud reported a technique of minimal cartilage resection and suture reattachment of the divided costal cartilages to the sternum and ribs. [42] Two small pieces of costal cartilage are resected, one piece adjacent to the sternum medially and another small lateral piece laterally. The judicious resection of cartilage ensures that only enough cartilage is removed to assure the posterior angulation of the rib is removed and the new position is the same height as the newly elevated sternum. A transverse osteotomy is performed, and then the sternum is untwisted, raised anteriorly, and secured in place. This decreases the formation of postoperative osteoid in the destroyed perichondrial sheaths, preventing the development of asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (Jeune syndrome). [42] The surgeons further implanted cartilage chips in the space between the ends of the cartilage to facilitate early cartilaginous growth. Reduced operating time, decreased pain, and increased early chest wall stability was noted.

Several other open techniques have been described. Haller et al described a technique of tripod fixation of the sternum. [43] The sternum is then flipped 180° and reattached to the cartilage as a free graft. This technique is not commonly used and has a higher complication rate compared with more conventional methods. [44]

Other innovative strategies include the use of substernal mesh bands for asymmetric pectus excavatum defects, [45] transsternal and parasternal struts in the Willital-Hegemann method, [46] and extensive retrosternal mobilization with tension measurements in the Erlangen technique. [47] Silicone implants have been introduced into the subcutaneous space above the sternum. [48] This results in cosmetic improvement but not physiologic improvement in the pectus excavatum.

Nuss described minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum in 1987. [49] The Nuss procedure involves insertion of a custom-bent, curved metal bar underneath the sternum through small lateral chest incisions. The bar is then turned, placing the convexity of the bar upward, correcting the pectus depression. The bar is then secured to the lateral aspect of the chest wall, ribs, or both, and then left in place for 2-4 years, after which it is removed in a second procedure. [50] (See the images below.) This minimally invasive approach avoids an anterior incision, and the extensive resection of deformed cartilages performed during open pectus approaches. Compared to open repair patients have a decreased length of stay, less pain, fewer activity restrictions, and quicker return to activities.

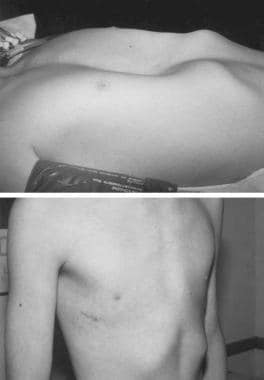

Preoperative (top) and postoperative (bottom) photograph of a 12-year-old boy prior to minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. Note the small lateral chest wall incision and the excellent appearance of the anterior chest with 100% correction of the pectus deformity.

Preoperative (top) and postoperative (bottom) photograph of a 12-year-old boy prior to minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. Note the small lateral chest wall incision and the excellent appearance of the anterior chest with 100% correction of the pectus deformity.

Several modifications to the Nuss procedure have been proposed. Implementation of a lateral stabilizing bar was the first major modification; it was a response to a substantial number of bar displacements. Hebra et al proposed the use of a three-point fixation method in conjunction with the stabilizing bar. [51] Bar dislodgement, which is more common in adult patients, can also be prevented by submuscular placement. [52]

Park et al suggested that stabilization of the pectus bar using a combination of a claw fixator and hinge plate may be more effective than use of a conventional stabilizer. [53] In their study, which involved the use of a pectus bar in 1816 pectus excavatum repairs, the investigators found that early bar dislocation rates in patients stabilized with the claw fixator/hinge plate combination was 0%, compared with 3.33% in those in whom a conventional stabilizer was used, 0.56% in patients who were stabilized with multipoint pericostal suture fixation, and 0.57% for those who were stabilized with the claw fixator alone. [53]

Another modification is the use of thoracoscopy to monitor safe passage of the clamp across the mediastinum. A survey of surgeons performing the Nuss procedure revealed that 61% use thoracoscopy on a routine basis. [54] Bilateral thoracoscopy has been reported to have the lowest rate of operative complications. [55, 56]

Nuss et al have recommended increasing the bar removal time to 3-4 years after the first procedure to lower the incidence of pectus excavatum recurrence. [50] Whether this prolongation will increase the number of positive outcomes has not been determined. Because of the various modifications, comparing results from one series with results from another can be difficult.

The use of thoracic epidural analgesia has also improved postoperative pain management in patients undergoing pectus excavatum repair of any type. [57] Meta-analysis has confirmed that postoperative epidural pain control can significantly decrease the incidence of pulmonary morbidity. [58] A predicted risk of 0.07% of permanent neurologic complications is estimated in adults with thoracic epidural catheterization. [59]

Controversy exists regarding the optimal age for a minimally invasive approach to pectus excavatum. There is evidence that repair in adults is more difficult and associated with more complications. Proponents support the utilization of the Nuss procedures in adults with important technical modifications, including forced sternal elevation, the use of multiple bars, and increased bar fixation to prevent rotation and migration. These modifications are largely due to the decreased compliance of the adult chest wall. The utilization of additional bars in a rigid adult chest effectively redistributes the pressure. The use of additional bars reduces the risk of incomplete correction, bar rotation, and malposition. There is also support for a hybrid minimally invasive procedure that includes a Nuss procedure in conjunction with an osteotomy and medial bar stabilization. [60] Ben and colleagues have documented acceptable outcomes and high patient satisfaction scores among patients with significantly asymmetric and severe pectus using a multiple bar technique. [61] Bar allergy complications can be mitigated with the use of metal allergy testing and the use of titanium bars. [62]

Outcomes of surgical repair

Historically, reports of outcomes and patient satisfaction following the Ravitch repair, and its variants, have been excellent. In several large series, satisfactory results were reported in more than 90% of patients with a metal strut in the repair. [63]

Complications of open repair of pectus excavatum are infrequent (8%), [42] of which the most common is a pneumothorax. It tends to be small and can be observed. Large pneumothoraces usually require only aspiration of air. Wound infection, pericardial effusion, and pericarditis can also occur but are rare. In a series of 320 patients with pectus deformities corrected by modified Ravitch repair, mild recurrent pectus excavatum deformity occurred in only 3 patients. [64] The affected patients only required minor cartilage resection at the time of bar removal. No perioperative deaths were reported.

The most serious complication of the classic Ravitch repair in children is impaired development of the thoracic cavity. Haller et al reported a series of 12 patients who underwent pectus excavatum repair and developed thoracic dystrophy. [65] In each instance, repair was performed in children younger than 4 years, and more than five ribs were resected. These patients presented with severe exercise intolerance and a clinically significant reduction in pulmonary function. [65]

The early age at which the operation is performed is not the suspected cause of the thoracic dystrophy; rather, the inappropriate surgical technique is now the suspected cause. This includes radical chondrocostal resection, extirpation of growth centers, and suturing together of the perichondrial strips retrosternally, causing cartilaginous growth behind the sternum. [66] Thus, most surgeons who perform the Ravitch procedure have modified the approach to a smaller incision, limitation of ribs resected, and to an older age population (adolescence or early adult).

In a prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter observational study of 327 patients to compare the outcomes of the standard modified Ravitch procedure with the outcomes of the Nuss procedure, outcomes were similar, and rates of complications were not statistically significant. [67] However, higher complications with the Nuss procedure have been noted in the literature, either as a result of the technique or the learning curve normally expected with a newer thoracoscopic technique. If the latter is the case, these complications should diminish over time. Decades follow-up reports are available for the Ravitch procedure, confirming excellent results. [42, 68]

Complications reported with the Nuss procedure have included the following [2, 51] : cardiac perforation; delayed tamponade as a result of the bar eroding into the aorta [69] ; and right ventricular injury, likely as a result of adhesions; and inferior vena cava occlusion due to mechanical compression by the Nuss bar. [70] A case of bilateral empyema with pericarditis, as well as four cases of thoracic outlet syndrome have been reported. [71, 72] In one patient, the bar had to be removed because of severe symptoms related to the brachial plexus and arm cyanosis, which was relieved with arm elevation. [71] Haller et al found this complication in open surgery, primarily in younger patients. [65]

The Nuss procedure has been used to treat pectus excavatum in adult patients, [52] with a higher reported complication rate (19-58%) in this population. Also, the higher forces needed to correct the deformity can result in bar displacement in as many as 50% of patients, as well as early metal fatigue and fracture of the bar. An estimated 32% of adults may require placement of an additional pectus bar. [73] The amount of force required to elevate the sternum has also been studied in pectus excavatum patients which correlated with postoperative pain. [74] Hebra and colleagues revealed that complications are underreported. [75] In addition, the majority of cases with life-threatening complications involved patients older than 16 years, previous chest surgery, and severe pectus with significant sternal rotation. [75] Additional modifications include sternal elevation, the use of bilateral thoracoscopy, proper bar selection, and stabilization, as well as appropriate training and mentorship. [75]

This radiograph reveals bar dislodgment in a patient with asymmetric pectus. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

This radiograph reveals bar dislodgment in a patient with asymmetric pectus. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

In a retrospective analysis that divided 680 patients into three age groups (7-14 y; 15-20 y; >20 y), Pawlak et al compared the results of the Nuss procedure in the surgical treatment of pectus excavatum in 680 patients, with a mean follow-up of 33 months. [76] Good and very good corrective effects were obtained in 97.7% of the total patient population; the rate of early non–life-threatening complications increased with age (youngest group, 24.3%; middle group, 37.8%; oldest group, 38.8%.P = 0.0063). [76]

Although failed or recurrent pectus excavatum repairs are technically more challenging, reoperative correction by the Nuss procedure is also possible. [77] Recurrence is related to the amount of time the bar remains in place. Nuss reported improvement in outcomes when the duration of bar placement was extended to 3 years, as compared to 1-2 years. [78]

Pectus Carinatum and Other Rare Deformities of the Anterior Chest Wall

Introduction

Pigeon chest or pectus carinatum occurs in 0.06% of live births and is the second most common congenital chest wall deformity. [79] Pectus carinatum comprises approximately 7% of all anterior chest wall deformities, has a male predominance (boy-to-girl ratio, 4:1), and is typically apparent at birth, tending to worsen as the child grows.

Pectus carinatum is typically thought of as a protrusion of the chest wall (the opposite of pectus excavatum), but it represents a spectrum of deformities that involve the costochondral cartilage (unilateral or bilateral) and sternum (superior or inferior). The defect may be asymmetrical, causing a rotation of the sternum with depression on one side and protrusion on the other.

Etiology

The pathogenesis of pectus carinatum, much like that of pectus excavatum, is obscure. Pectus carinatum has been postulated to represent an overgrowth of ribs or costochondral cartilage. A genetic predilection may be present, because 26% of patients have a family history of chest wall deformity. Furthermore, 15% of patients also have scoliosis, congenital heart defects, cardiomegaly due to cardiomyopathy, Marfan syndrome, or other connective tissue disorders.

Presentation

Pectus carinatum can be divided into two distinct types of deformities. The chrondromanubrial form results in protrusion of the manubrium and is known as Currarino-Silverman syndrome. Chondrogladiolar carinatum is characterized by protrusion of the body of the sternum and costal cartilages; a lateral depression of the ribs results, which is known as runnels or Harrison grooves. Chondrogladiolar protuberance, which comprises 90% of pectus carinatum deformities, has been described as appearing like the result of a giant hand crushing the chest from each side. Pectus arcuatum is often described as a type of carinatum deformity; however, this is a unique form of pectus caused by the premature obliteration of the sternal sutures. [80]

Symptoms from pectus carinatum are more common in adolescents and range from severe shortness of breath on minimal exertion, reduced endurance, and exercise-induced asthma. Chest wall excursions are limited due to the fixed AP diameter of the thorax, resulting in increased residual volume, tachypnea, and compensatory diaphragmatic excursions. Chest wall pain, difficulty finding appropriately fitting clothing, and psychosocial discomfort are common symptoms.

Surgical repair can result in an improvement of 9% in the vital capacity. [3]

Treatment

External bracing is the initial treatment of choice, with success rates above 70% when the braces are worn as prescribed. [10] When de Beer et al tested the use of a dynamic compression brace for pectus carinatum in 286 patients who had a pressure of initial correction (PIC) of 10.0 pounds per square inch or less, 78 patients completed brace treatment, 181 patients were still wearing the brace, and 27 patients abandoned treatment. [81] Adverse events were minor, including skin lesions (1%) and vasovagal reactions at the beginning of therapy (1%). Additional barriers to brace compliance include pain and psychosocial discomfort.

Although successful applications of orthotic bracing has been reported, surgical repair is performed in the context of brace failure related to noncompliance or chest wall rigidity. [82, 83] Wearing a chest brace for 16-23 hours a day raises patient compliance issues and is least successful in the more severe cases. [84] Patients in whom orthotic intervention failed had a higher Haller index (2.85 vs 2.05), a greater angle of sternal rotation (27.3º vs 14.8º), and an increased asymmetry index (1.23 vs 1.06). [85]

Ravitch reported the first surgical repair of a carinatum defect in 1952. [86] He described a method in which resection of abnormal cartilage was combined with double osteotomy of the sternum to elevate the defect. Other surgical attempts at repair were described in which part of the sternum was resected, up to and including a complete subperichondrial resection.

The modern method of repair is based on the procedure described by Welch and Vos in 1973. [87] Like the Ravitch technique utilized to correct pectus excavatum, they performed subperichondrial resection of the abnormal cartilage and preserved the sternum. Transverse osteotomy of the sternum was made and, when combined with fracture of the posterior cortex of the sternum, allowed posterior displacement and untwisting of the sternum. In 1987, Shamberger and Welch published their experience with this repair in 152 patients, reporting satisfactory results were achieved in all but 3 patients (98%). [88] Fonkalsrud and Anselmo reported a less extensive technique with minimal cartilage resection and suture reattachment of the cartilage segments to the ribs and sternum, combined with two to three transverse sternal osteotomies. [3] They used a temporary support bar anterior to the sternum and ribs for 6 months.

Minimally invasive surgical correction is an option for treatment of pectus carinatum. [89] Ventral chest wall dissection is performed by insufflation of carbon dioxide after insertion of two subpectoral trocars. Endoscopic-assisted rib resection is then performed, followed by axial reanastomosis of the divided cartilages. Transsternal struts are then placed using endoscopic guidance, and sternotomies are performed using a combination of endoscopy and a mini–open incision (2.9-4.7 cm). [90] Operative times average 180 minutes, which compares favorably with open techniques.

Complications and outcomes

In general, complication rates for the open resection technique are low. Excellent results were noted in 97% of patients at a follow-up of 8 years, [3] with seroma occurring in 2 of 154 patients and 1 pneumothorax. Long-term complications of asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy were not seen in this group, because preservation of the costal cartilages maintained thoracic flexibility.

In a minimally invasive repair of pectus carinatum group, 33 of 37 patients reported an excellent outcome, and 4 patients reported a good outcome after a follow-up of 29 months. [90] These results were maintained even after strut removal. However this technique is not widely adopted due to its technical challenges.

Poland Syndrome

Introduction

Poland syndrome—named after Albert Poland, who first described this entity while attending medical school—refers to a spectrum of disorders that involve hypoplasia of the chest wall. This may include (alone or in combination) the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, serratus anterior, ribs, and soft tissue. Deformities of the arm and hand may also be observed.

The incidence of Poland syndrome is approximately 1 case per 32,000 live births, and its occurrence is almost always sporadic or nonfamilial. It is three times more common in boys than in girls, and there is right-sided involvement in 75% of patients.

Etiology

Multiple theories regarding the etiology have been proposed, including abnormal migration of embryonic tissue, hypoplasia of the subclavian artery, or in utero injury from attempted abortion. However, none of these theories are widely accepted.

Rare associations of Poland syndrome with other diseases have been noted. Leukemia has been observed in some patients with Poland syndrome, and an association with Möbius syndrome (unilateral or bilateral facial palsy and abducens oculi palsy) has been reported.

Presentation

The presentation of patients with Poland syndrome varies according to the type of defect, with most presenting with cosmetic complaints. In patients with notable bony defects, lung herniation may be noted early in childhood, especially with coughing or crying. Some patients may have a functional flail chest and present with respiratory compromise. The lung itself is otherwise normal in these patients. In those with significant muscular and soft-tissue involvement, Poland syndrome may become evident secondary to exercise intolerance.

Treatment

Treatment of patients with Poland syndrome depends on the type of defect. Ravitch first described the reconstruction of the chest wall in patients with rib aplasia with autologous rib graft in 1966, and this remains the standard repair. [91] This repair involves exposure of the chest wall through a transverse incision and subperichondrial rib resection on both sides, with care taken not to violate the pleural cavity. The third, fourth, and fifth costal cartilages are removed in their entirety, whereas the sixth and seventh costal cartilages are resected to the point where they join the costal arch. A transverse osteotomy through the sternum is performed, which allows correction of the sternal rotation. Rib grafts taken from the contralateral fifth or sixth rib are used to reconstruct the chest in patients with rib aplasia. A relatively recent modification has included changing to a vertical limited skin incision. [92]

Breast reconstruction may be required in female patients. Techniques include implants and latissimus dorsi flaps, often in conjunction. Reconstruction is performed after puberty to optimize the match between the normal and reconstructed breast.

Endoscopically assisted reconstruction of Poland syndrome has been reported. Initially, tissue expanders are inserted followed by a second-stage latissimus dorsi harvest and reconstruction using only endoscopic techniques. [93]

Outcomes

Outcomes of surgical correction of Poland syndrome depend on the type of defect and the expectation of the patient. Some variants of Poland syndrome, such as diffuse rib aplasia without depression, are not surgically correctable at all. Therefore, patients should be carefully counseled before surgery.

Jeune Syndrome

Introduction

Jeune syndrome, or asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy, is a failure of chest wall growth in utero resulting in a narrow chest cavity and pulmonary hypoplasia. In 1954, Jeune first described the syndrome in a newborn. [94] Although some patients with this syndrome may not live past infancy, many cases are now recognized with prolonged survival, and surgical options have been developed that allow for the potential of chest wall growth.

Jeune syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, and no chromosomal abnormalities have been seen in association with it. The pattern of expression and the degree of pulmonary hypoplasia vary, which accounts for the longevity in certain patients.

Treatment

Lateral thoracic expansion is an interesting technique that has been developed by Davis et al to enlarge the thoracic cage in patients with Jeune syndrome. [95] The procedure involves separating the ribs from their periosteum, dividing them, and then plating them together using titanium struts to increase chest diameter. One side is addressed at a time, after radiologic evidence of healing (periosteal new bone formation) is noted. Although the chest wall is enlarged, it remains a fixed cylinder, and respiratory efforts entirely depend on diaphragmatic movement. However, the increase in thoracic volume provides clinical improvement and many years of growth, and freedom from ventilator-dependence have been reported. [95]

Complications

An acquired form of thoracic dystrophy has been recognized as a complication of pectus excavatum when repaired in younger children (see Surgical Repair of Pectus Excavatum). Reports of operative chest expansion in this group of patients have demonstrated encouraging short-term results. [95]

Sternal Defects

Sternal defects can be categorized into four types, all of which are rare: thoracic ectopia cordis, cervical ectopia cordis, thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis, and cleft sternum.

Thoracic ectopia cordis

Thoracic ectopia cordis, or naked heart, is the result of failure of somatic structures to form over the heart, leaving it completely exposed. The sternal anomalies run a spectrum from completely split to almost completely intact with a central defect. The survival of patients with thoracic ectopia cordis has historically been poor. Only 3 successful repairs in 29 attempts have been described.

Cervical ectopia cordis

Cervical ectopia cordis differs from thoracic ectopia cordis by the amount of superior displacement of the heart. Craniofacial abnormalities are often present and extremely severe. No survivors or successful repairs have yet been documented.

Thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis

Patients with thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis have an inferiorly displaced heart underlying an inferiorly cleft sternum. The heart is covered by membrane or thin skin. Inferior displacement of the heart results from a semilunar defect in the pericardium and diaphragm. Abdominal wall defects are also common. The association of cardiac, pericardial, diaphragmatic, abdominal wall, and sternal defects is also referred to as the pentalogy of Cantrell. Surgical repair of thoracoabdominal ectopic cordis has been more successful, when compared with the other forms of ectopic cordis.

Alloplastic materials (methyl methacrylate struts) have been used in the reconstruction of the sternal defect, and a successful 10-year follow-up of a case has been reported. [96] Initial pectoral skin flaps were used for coverage of the exposed heart, followed by definitive reconstruction. Costochondral flaps added rigidity to the repair, and a muscle flap was also used for closure of the defect. Autologous ribs have been used with minimal morbidity.

Cleft sternum

Cleft sternum is the least severe of these four sternal anomalies, because the heart is covered and is in a normal position. Overlying the heart is a partially or completely cleft sternum, and a partial split is more common than a complete split. Several clinical associations are seen with cleft sternum, but cardiac defects are rare. A bandlike scar often extends from the sternum to the umbilicus or superiorly to the neck. Hemangiomas of the head and neck can also be found.

In most infants, cleft sternum usually does not cause any detectable symptoms. On occasion, respiratory symptoms result from the paradoxical motion of the sternal defect. The primary indication for repair is to protect the heart. Repair is performed through a midline incision, and the two halves of the sternum are approximated with nonabsorbable suture. In incompletely cleft sternums, a wedge of cartilage is occasionally removed from the base of the cleft to facilitate approximation. Repair is best performed in infants, because their chest wall is the most pliable. [97, 98]

Acquired Chest Wall Defects

Postoperative chest wall defects may result from tumor extirpation or may be iatrogenic after failure of anterolateral thoracotomy or clamshell closure. There is associated lung herniation and sympathetic pleural effusions, which may become infected, resulting in empyema and a trapped lung.

Anterolateral herniation is seen most commonly following minimally invasive approaches to mitral valve repair, especially robotic-assisted repairs. Improper approximation of the incision results in dehiscence or fracture of the costal cartilages. This is of particular significance in immunosuppressed patients, such as those following lung transplant who are deconditioned pretransplant and exhibit poor wound healing posttransplant due to high-dose steroid immunosuppression. Surgical repair of these defects is complex and may require several reconstructive strategies, including the use of bioabsorbable materials (eg, BioBridge or AlloDerm patches). Most importantly, the trapped lung must be completely decorticated to allow reduction of the lung hernia and complete expansion within the thoracic cage. This may be performed thoracoscopically or through the chest wall defect, if accessible. Also, all prior hardware including stainless steel wires and cables need to be explanted to reduce the risk of residual infection.

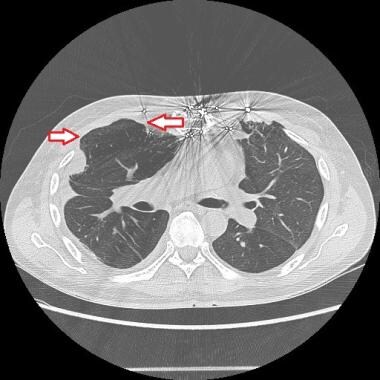

The red arrows indicate lung herniation in a patient following double lung transplantation. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

The red arrows indicate lung herniation in a patient following double lung transplantation. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

Perioperative Care After Pectus Correction

Pain control

Pain management is imperative in the pectus population to assure early mobilization, prevent respiratory complications, secure a timely discharge, and patient overall well-being. Symptom management remains important after discharge to assure the resumption of normal daily activities, as well as return to work and educational pursuits in the context of the metal strut typically in place for a minimum of 1 year.

The pathophysiology of pain after pectus surgery includes inflammatory, neuropathic, myofascial, and osseous mechanisms. Hence, a multimodal approach is strongly recommended, even when employing less-invasive approaches, such as the Nuss procedure. Nonopioid oral analgesics, anticonvulsants, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, topical, physical medicine interventions, opioid analgesics, and regional anesthesia are all widely utilized. [99] Regional blocks include epidurals, erector spinae catheters, and cryoneurolysis.

Cryoneurolysis is an important nonopioid mechanism of pain control. Intraoperatively, a handheld probe is applied to the intercostal nerve, resulting in Wallerian degeneration, or reversible neuronal injury, of the peripheral sensory nerve. [100] This therapy has been reported to decrease opioid requirements and length of stay after pectus surgery in the pediatric and adult literature. [101, 102]

Among pediatric patients, cryoneurolysis led to decreased narcotic use compared to patient-controlled analgesia and epidurals, as well as a shorter length of stay without increased complications. [103] Among adults, there are reports of an increased risk of higher neuropathy scores. [104] A retrospective study by Zobel found that, among patients undergoing a Nuss procedure, those older than 21 years were more likely to experience neuropathic pain and prolonged numbness. [105] More prospective studies are required to evaluate the benefits of cryoneurolysis in adult thoracic patients.

Mobilization

Early mobilization includes occupational and physical therapy consultations on postoperative day 1. It is imperative for the surgical team to work closely with ancillary staff to ensure early ambulation and pulmonary toilet, and to educate patients so that they understand immediate postoperative restriction.

Nonsurgical Treatment of Chest Wall Deformities

Chest wall deformities are a diverse group of anatomic defects that often have cardiopulmonary and psychosocial consequences. While some patients are asymptomatic, many experience life altering symptoms throughout childhood and adulthood. In addition, due to the potential association with connective tissue disorders, congenital defects, and psychological maturation, the authors of this chapter employ and recommend a multidisciplinary approach. Utilizing an individualized approach, the treatment team may include pulmonologists, cardiologists, geneticists, and mental health experts. From a surgical standpoint the pediatric, thoracic, and cardiothoracic surgical specialists work in coordination to assure the appropriate approach, timing, and expertise for each patient. This collaboration includes the clinical setting and extends into the operating theater.

Management of chest wall deformities is made on the basis of patient factors, including the anatomy and pathophysiology of the defect, involved organ systems, comorbid conditions, age, and surgeon preferences. On the basis of the risk-benefit profile and outcomes of operative management, patients and caregivers frequently request information about nonoperative management and associated outcomes.

Pectus excavatum

Interventions for pectus excavatum are largely surgical. However, there are nonsurgical modalities, such as use of a vacuum bell, and noncorrective interventions, such as prosthetics.

Patient selection is important. Viable candidates for nonsurgical treatment should have an adequate, flexible chest wall and a pectus depth of less than 1.5 cm. Due to the rigidity of the adult chest wall, nonsurgical options are less effective in this population. In addition, patient cooperation and motivation are imperative. The bell needs to be worn 12-18 months, for several hours each day. Consistency and compliance are important to optimize results. Cardiac anomalies, coagulopathies, and connective tissue disorders are contraindications for vacuum bell use. [106]

The vacuum bell has been employed for over 100 years and involves the application of a suction cup that creates a vacuum on the chest wall. The healthcare provider or patient activates a pump to reduce the pressure. In a retrospective study of 186 patients, Toselli and colleagues identified complete correction in 17% of patients; however, the withdrawal rate was over 30%. [107] The predictors for success included a sternal depth below 1.8 cm and at least 12 months of treatment. [107] In a single-center study, Obermeyer demonstrated that children younger than 11 years who had a chest wall depth less than 1.5 cm and 12 consecutive months of use had the best outcomes. [108] Reported side effects include chest wall pain, upper extremity paresthesias, chest wall hematoma, and skin irritation. This technique can be utilized to facilitate operative repair. Shier et al utilized vacuum bell technology to assist with Nuss bar placement. [109] Surgeons used the technology to elevate the sternum and ribs away from the pericardium to facilitate the thoracoscopic guided placement of a Nuss bar. [109]

Although many patients with pectus do not experience physiologic symptoms, they may experience significant psychosocial distress. For patients interested in improving the aesthetics of their chest wall without correction of the bony defect, options include autologous fat grafting, [106] and the placement of prosthetics, including breast augmentation, to cover the defect. [110] It is important to discuss the prospect of future definitive corrective surgery prior to the placement of any implant with an experienced pectus surgeon, as it will affect the conduct of any repair and the implants may require removal. Hence, patients should have a complete evaluation with an experienced surgeon trained in the physiology and repair of chest wall deformities.

Pectus carinatum

In the context of pectus carinatum, nonoperative management is the first line of therapy for most patients. Bracing compresses the sternum and costal cartilage by exerting consistent pressure to the anterior chest wall. Efficacy requires an active and maintenance phase for corrections with wearing a specially fitted brace 12-24 hours a day in the active phase, and a few hours a day, based on surgeon recommendation, in the maintenance phase. The total treatment duration can last 1-2 years. Some surgeons provide a period of surveillance. Bracing in the context of carinatum is effective, with excellent clinical and psychosocial results. It is important to note that adults with less-compliant chest walls, those with severe deformities, and those with significant asymmetry often require longer treatment duration to achieve the desired outcome. [106]

-

A 16-year-old boy with severe pectus excavatum. Note the appearance of the caved-in sternum and lower ribs.

-

Pectus carinatum. Photograph courtesy of K Kenigsberg, MD.

-

Preoperative (top) and postoperative (bottom) photograph of a 12-year-old boy prior to minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum. Note the small lateral chest wall incision and the excellent appearance of the anterior chest with 100% correction of the pectus deformity.

-

This image depicts a high Haller index pectus excavatum causing displacement of heart into left chest. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

This image demonstrates a high Haller index pectus excavatum that is compressing the right atrium and inferior vena cava. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

An anteroposterior radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

A lateral radiographic view of the double bar technique is shown. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

This radiograph reveals bar dislodgment in a patient with asymmetric pectus. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

The red arrows indicate lung herniation in a patient following double lung transplantation. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

-

Shown is an anterior chest lung herniation after a prior thoracotomy infection. Courtesy of Reshma M Biniwale, MD.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Pectus Excavatum

- Surgical Repair of Pectus Excavatum

- Pectus Carinatum and Other Rare Deformities of the Anterior Chest Wall

- Poland Syndrome

- Jeune Syndrome

- Sternal Defects

- Acquired Chest Wall Defects

- Perioperative Care After Pectus Correction

- Nonsurgical Treatment of Chest Wall Deformities

- Show All

- Media Gallery

- References