Practice Essentials

Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death and the number 1 cause of death from infectious disease in the United States. About 1 million adults in the US are hospitalized with pneumonia every year, and about 50,000 die of this disease. Globally, pneumonia is the leading cause of death in children younger than 5 years. There are 120 million cases of pneumonia reported each year, and over 10% (14 million) progress to severe episodes. An estimated 880,000 deaths from pneumonia occured in children younger than 5 years in 2016. [1]

The joint guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend radiographic confirmation of a pneumonia diagnosis prior to treatment because of the inaccuracy of a diagnosis based on clinical signs and symptoms alone. [2]

Imaging modalities

Chest radiography with posteroanterior and lateral views is the preferred imaging examination for the evaluation of typical bacterial pneumonia. Ultrasonography has the potential to more accurately and efficiently diagnose pneumonia, as well as pleural effusions, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and pulmonary contusions. Because lung ultrasonography can be performed at the bedside in an average of 13 minutes and lacks ionizing radiation, it is a good diagnostic option in primary care and emergency department settings.

Radiography

When patients present with fever, chills, or cough, pneumonia is suggested on the basis of focal or diffuse opacities.

Controversy exists with regard to the time required for an opacity to appear on chest radiographs. The vast majority of opacities appear within 12 hours. When patients are referred from the community to the radiologist, adequate time has usually elapsed for its detection. However, when nosocomial pneumonia is suspected, these patients may undergo chest radiography within a few hours, when opacities may not yet be visible on radiographs. [10, 11]

In immunosuppressed patients, especially those with coexistent neutropenia, diabetes, alcoholism, or uremia, the appearance of infiltrates may also be delayed.

Other findings that suggest the presence of pneumonia include air bronchograms; the silhouette sign; parapneumonic effusions; and complications of pneumonia, such as lung abscesses and atelectasis.

Findings that have been associated with an increased mortality include bilateral pleural effusion and multilobar pneumonia.

In patients with underlying structural lung disease, the appearance of the various signs of pneumonia may not be straightforward. Narrowing the differential diagnosis of pneumonia into typical and atypical forms on the basis of radiographic appearance alone is not reliable, as was shown in a prospective study by Fang et al. [12]

Resolution of radiographic findings

The change in infiltrates on chest radiographs is not necessarily correlated with the activity of clinical disease. In some patients, chest infiltrates may worsen with the start or treatment, despite clinical improvement.

Pneumonia that is slow to resolve after appropriate antibiotic therapy can be a problem. In general, nonresolving pneumonia is thought to be present when a patient does not improve clinically or when a radiographic infiltrate resolves slowly despite adequate and appropriate antibiotic therapy. About 10% of diagnostic bronchoscopy procedures and 15% of pulmonary consultations are performed to evaluate a nonresolving infiltrate.

The most common cause of unnecessary invasive evaluation is a failure to appreciate the length of time that infections need to clear radiologically. Studies have shown that impaired host defenses are more important determinants of delayed resolution than the infecting pathogen.

Host factors responsible for delayed resolution of pneumonia include age older than 50 years, smoking, and chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and alcoholism.

Bacterial pneumonias usually tend to be unilobar and have cavitary lesions and effusions. Atypical pathogens can cause multilobar involvement with nodular or reticular infiltrates, lobar or segmental collapse, or perihilar adenopathy.

Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most frequent bacterial pathogen in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) worldwide. [13] S pneumoniae causes 10-50% of CAP. Radiographic consolidation of the alveoli begins in the peripheral airspaces (see the image below). The disease usually causes a lobar or segmental pattern, and a patchy bronchopneumonic pattern involving the lower lobes is seen in the elderly. A striking characteristic of S pneumoniae infection is its tendency to involve the pleura. Parapneumonic effusions are common in pneumococcal pneumonia. [14]

Image in a 49-year-old woman with pneumococcal pneumonia. The chest radiograph reveals a left lower lobe opacity with pleural effusion.

Image in a 49-year-old woman with pneumococcal pneumonia. The chest radiograph reveals a left lower lobe opacity with pleural effusion.

In a study of bacteremic pneumococcal patients, 50% had clear radiographs at 9 weeks, as compared to 5 weeks in nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia.

In patients older than 50 years with both alcoholism and COPD, 60% have an abnormal chest radiograph at 14 weeks. In patients younger than 50 years with bacteremia and no underlying illness, 40% have an abnormal chest image at 2 weeks. For the group as a whole, 37% have residual consolidation at 4 weeks, with complete resolution by 18 weeks in almost all patients.

In one study, despite therapy during the initial phase of illness, 52% of bacteremic patients, as compared to 26% of nonbacteremic patients, had radiographs showing deterioration. Jay and colleagues recommended that an appropriate interval for serial radiographic examination is 6 weeks, unless otherwise indicated by a patient's worsening clinical status. [14]

Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia

H influenzae pneumonia (see the image below) is commonly seen in COPD patients who are smokers; in the elderly; and in those with alcoholism, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, or immunocompromise. This organism can be present in up to 38% of outpatients and 10% of hospitalized patients with CAP.

Image in a 48-year-old patient with Haemophilusinfluenzae pneumonia. The chest radiograph shows bilateral opacities with a predominantly peripheral distribution.

Image in a 48-year-old patient with Haemophilusinfluenzae pneumonia. The chest radiograph shows bilateral opacities with a predominantly peripheral distribution.

In most patients, radiographs demonstrate a patchy bronchopneumonic pattern, but segmental and lobar consolidation may be seen. Therefore, H influenzae pneumonia is indistinguishable from pneumococcal pneumonia. Pleural effusion is a common finding. Radiographs usually show a multilobar infiltrate and pleural effusions in 50% of cases. Resolution is usually slow.

Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia

The radiographic patterns seen in Klebsiella pneumonia include patchy bronchopneumonia and dense lobar consolidations. The alveoli are filled with large amounts of fluid and mucoid suppurative exudates that may cause the volume of the affected lung to increase with bulging of the interlobar fissures. Although these findings are thought to be characteristic of Klebsiella pneumonia, they may also be seen in other causes of pneumonia.

There is a strong tendency for abscess formation as well as pleural involvement. Cavities may develop rapidly after the onset of illness, and these may be associated with massive lung gangrene.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia

P aeruginosa pneumonia has a characteristic predilection for the lower lobes. Patchy bronchopneumonia or extensive consolidation may be present. Involvement may be unilateral or bilateral and extensive. Extensive necrosis may be seen, with the formation of parenchymal abscesses. Massive bilateral consolidation is usually associated with a poor prognosis. Nodular infarcts may occur in the lung parenchyma.

Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia

S aureus pneumonia may be seen as a complication of influenza, particularly during an epidemic. This type of pneumonia usually begins in the peripheral airways rather than in the acini proper. In adults, patchy bronchopneumonia is more common and often bilateral, though lobar consolidation may be seen. Late development of abscesses is relatively common. When staphylococcal pneumonia occurs as a complication of influenza, it is usually rapidly progressive, with extensive bilateral pneumonia that resembles pulmonary edema.

In children, it is usually a lobar or multilobar consolidation, rapidly progressing with the development of pneumatoceles and/or empyema. The presence of pneumatoceles in children is virtually diagnostic of staphylococcal pneumonia. Rapid progression is seen with lobar or multilobar consolidation. Pneumatoceles may rapidly develop, and empyema is frequent. [15]

Q fever pneumonia

Q fever is caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii found in feces, urine, and milk of infected animals. Unilateral, single segmental opacities is the most common finding, but patchy and lobar infiltrates are also found in some patients. In the majority of patients, the lower lobes are affected. The left lung is more commonly affected than the right lung, but involvement of both lungs is possible. [16]

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is increasingly being used in clinical practice, but various groups have questioned its usefulness in evaluating pneumonia. Their reports have suggested that its usefulness in the diagnosis of pneumonia is limited to the following settings:

-

Evaluation of an indistinct, abnormal opacity depicted on a chest radiograph

-

Assessment of patchy, ground-glass, or linear/reticular opacities on chest radiographs

-

Confirmation of pleural effusion

-

Examination of neutropenic patients with fever of unknown origin (with the use of ultra–thin-section CT scanning)

In a retrospective study, by Komiya et al, of elderly patients (N=86) admitted for acute K pneumoniae pneumonia, analysis of thin-section CT findings found that lobar pneumonia appeared to be an independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality. Twenty-five patients (29%) died in hospital, and they had a greater incidence of lobar pneumonia pattern (40% in nonsurvivors vs 10% in survivors), low albumin level, and higher levels of aspartate aminotransferase and C-reactive protein on admission. [17]

Chest CT may be requested in cases of Q fever in which radiographic findings are confusing or coexistent disease is suspected. High-resolution CT (HRCT) features of acute Q fever pneumonia include airspace consolidation or nodules with halos of ground-glass opacity in a segmental, patchy, or lobar distribution. [4]

In clinical practice, coinfection with multiple organisms is not rare, and underlying abnormalities of the lung parenchyma usually predispose patients to pneumonia. Hence, the overall clinical and radiologic picture must be considered. [18]

(CT scans of typical bacterial pneumonia are provided below.)

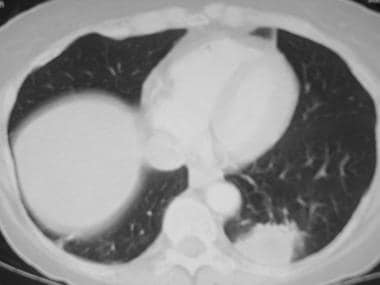

Image in a 49-year-old patient with pneumococcal pneumonia. This chest CT shows a left upper lobe opacity extending to the periphery.

Image in a 49-year-old patient with pneumococcal pneumonia. This chest CT shows a left upper lobe opacity extending to the periphery.

Ultrasonography

The literature indicates that ultrasonography can aid in the differentiation of consolidation and effusion. Consolidated lung tissue may appear as hypoechoic areas with blurred margins. The texture varies with the amount of aeration, being more heterogeneous with aeration and homogeneous with dense consolidation. [19] Haaksma and colleagues reported that the use of extended ultrasonographic assessment with the inclusion of dynamic air bronchograms and color Doppler imaging improved the accuracy of distinguishing pneumonia from atelectasis in critically ill patients with consolidation on chest radiographs. [20]

Ultrasonography may also help in diagnosing empyema and abscesses. [11, 21]

The role of ultrasonography in clinical practice is limited to the identification and quantification of parapneumonic effusions. This area can then be marked for subsequent diagnostic or therapeutic thoracentesis.

-

Image in a 49-year-old woman with pneumococcal pneumonia. The chest radiograph reveals a left lower lobe opacity with pleural effusion.

-

Image in a 48-year-old patient with Haemophilusinfluenzae pneumonia. The chest radiograph shows bilateral opacities with a predominantly peripheral distribution.

-

Image in a 49-year-old patient with pneumococcal pneumonia. This chest CT shows a left upper lobe opacity extending to the periphery.

-

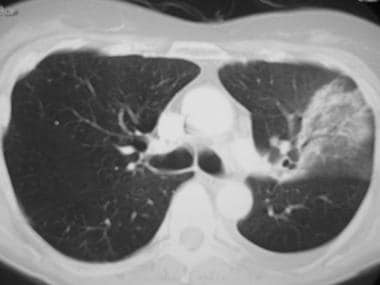

Image in a 50-year-old patient with Haemophilus influenzaepneumonia. The chest CT shows a very dense round area of consolidation adjacent to the pleura in the left lower lobe.