Practice Essentials

Nasal fracture and blowout (orbital floor) fracture (ie, a break in the floor or inner wall of the orbit or eye socket) are the most common injuries from craniomaxillofacial trauma. Nasal fractures are easily diagnosed by clinical signs such as pain and crepitus. However, blowout fractures are frequently asymptomatic and are easy to miss without computed tomography (CT) scanning. [1]

Nasal bone fractures represent the most common facial bone fractures, accounting for 40-50% of cases. Nasal fractures are generally associated with physical assault, falls, sports injuries, and traffic accidents. Bony nasal trauma may occur as an isolated injury or in combination with other soft tissue and bony facial injuries. [2]

Although nasal fracture is the most common facial fracture in both adults and children, [3] it often goes unnoticed by physicians and patients. Patients with nasal fracture usually present with some combination of deformity, tenderness, hemorrhage, edema, ecchymosis, instability, and crepitation; however, these features may not be present or may be transient. [4, 5, 6] To further complicate the matter, edema can mask underlying nasal deformity, crepitation, and instability; thus, many physicians and patients fail to pursue further diagnosis and appropriate treatment. [7]

If radiographic evaluation is warranted, this is best done when other facial fractures are suspected in combination with a nasal fracture, because isolated nasal fractures are treated on the basis of physical examination alone. The fact that patients may have displaced nasal fracture and normal-appearing plain radiographic findings should be emphasized. [6, 8, 9]

A thorough history should document the mechanism of injury in nasal fracture, as well as the vector in which the force was applied, and should reveal whether any prior nasal traumas or surgeries have occurred. It is also important to elucidate whether the patient experiences any nasal obstruction after the injury. In the acute phase, simple application of ice and analgesia may be very helpful for reducing edema and discomfort. More severe facial trauma may require assessment and stabilization of the airway via appropriate Advanced Trauma Life Support or Pediatric Advanced Life Support protocols. [2]

Nasal soft tissue wounds are cleansed and foreign bodies removed. Small lacerations can be closed with porous surgical tape strips, skin glue, or fine sutures. [2]

Reduction of nasal fractures is not always required. No further intervention is needed if there is no deformity or if the patient is unconcerned about the aesthetic appearance. However, it is worth counseling patients that wearing of spectacles may be affected by a change in nasal shape. If swelling interferes with an adequate examination, reassessment should occur 5-7 days later, after the patient has had a chance to apply ice and keep the head elevated. For particularly severe edema, a short course of oral steroids may be helpful. Reduction of displaced bone fragments should occur within 2 weeks of injury, as the nasal bones will heal and fixate; manipulation after this time will be challenging and may require osteotomies to mobilize the bones once more. Some recommend CT guidance for the procedure to improve precision and optimize patient outcomes. [2]

Preparation for reduction of nasal fracture involves an informed-consent discussion that details available options for the patient, as well as risks and anticipated results. Most nasal fractures can be left to heal on their own, provided that the patient understands that long-term cosmetic deformity and nasal obstruction are liable to result. In the acute period, within about 2 weeks after the injury, most nasal fractures can be reduced in a closed fashion, but after this period, closed osteotomies or even a formal open rhinoplasty may be required for definitive management. [2]

Nasal bone fracture is the most common facial fracture; however, surgery does not guarantee reduction, and complications such as undercorrection, overcorrection, and deviation may occur. [10]

The most common adverse outcome of nasal fracture reduction is dissatisfaction with the result, from a cosmetic or functional standpoint, or both. In the event of dissatisfaction, which occurs in up to 20% of patients, open septorhinoplasty performed at least 3-6 months after closed reduction may be an option. The patient should expect to experience pain, bleeding, swelling, bruising, and nasal obstruction in the early postprocedure period. [2]

Imaging modalities

Although use of plain images is not recommended, preferred examination includes acquisition of Waters (occipitomental) and lateral nasal views if plain films are obtained. It should be noted that plain radiographs only serve to confuse the clinical picture in most cases. Plain radiographs do not allow identification of cartilaginous disruptions, fractures, shearing, and injury in general. Plain radiographs also do not provide sufficient information on injury severity and displacement—2 important aspects essential to emergent and delayed management and surgical planning.

A good physical examination of the internal and external nose remains the method of choice for detecting and assessing nasal fractures.

For questionable fractures and fractures that may be associated with other facial trauma, CT scanning of facial bones without contrast is an excellent choice. Modern multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners have revolutionized trauma imaging and provide a fast, safe, cost-effective, and sensitive means of assessing trauma of the bone and soft tissues. Three-dimensional reconstructions are easily derived from these scanners and readily show the degree of displacement when trauma is substantial. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

Ultrasonography may be used to detect local and superficial fractures, but it can be difficult to see the entire nasal bone and neighboring bones with this modality. [13, 16, 17]

A definitive diagnosis of nasal fracture (nasal dorsum and nasal wall) can be made, when necessary, on the basis of all clinical data combined with radiographic findings (nasal bones and Waters view) and CT scans. [18] However, radiographs have a reliability rating of only 82%. [19]

(See the images below.)

Nasal fracture. Posteroanterior view shows displaced septum from the maxillary crest and a deviated nasal root to the patient's right.

Nasal fracture. Posteroanterior view shows displaced septum from the maxillary crest and a deviated nasal root to the patient's right.

Nasal fracture. Waters view shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Nasal fracture. Waters view shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

When left untreated, nasal fracture can result in unfavorable appearance and function, especially when the underlying structural integrity of bone and cartilage is lost. [5, 20] Untreated nasal fractures account for the high percentages of rhinoplasty and septoplasty procedures performed months to years after the initial trauma occurs. Thus, appropriate treatment is best rendered in a timely manner, before scarring and soft tissue changes become evident. As always, thorough history-taking and physical examination should precede radiographic evaluation.

Pathophysiology

Nasal bone fractures account for 50% of all facial fractures; most of these injuries involve the cartilaginous lower two thirds of the nose.

Protrusion of the nasal bones out of the facial plane and central location within the face predispose the nose to injury. Although isolated nasal fractures are the most common facial fractures, they may be associated with fractures of the zygomatic-orbital-maxillary complex and fractures of the skull base. [2]

Lateral impact injury is the most common type of nasal injury leading to fracture. [21] Nasal fracture and displacement without septal fracture usually occur with weaker applied forces; however, with increased force, displacement of bilateral nasal bones may be noted, and the septum may become dislocated and fractured. [22]

Approximately 80% of fractures occur at the lower one third to one half of the nasal bone. This area represents a transitional zone between the thicker proximal and thinner distal segments.

Other injuries commonly associated with nasal fracture include midface injuries involving frontal, ethmoid, and lacrimal bones; naso-orbital ethmoid fractures; orbital wall fractures; cribriform plate fractures; frontal sinus fractures [12] ; and maxillary Le Fort I, II, and III fractures. [4, 6, 23, 24, 25, 26]

Epidemiology

In the United States, approximately 50,000 people experience nasal fracture each year, [18] accounting for approximately 40% of all bone injuries. Nasal fractures are twice as common in males as in females. [2] Fights and sports injuries are the most common causes of nasal fracture among adults, followed by falls and vehicle crashes. Play and sports account for the majority of nasal fractures in children. Physical abuse should be considered when children and women with nasal fracture are evaluated. Nasal fracture may occur in isolation, but it is commonly associated with other facial injuries and fractures. [3]

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study reported in 2020 that nasal fractures represent a significant liability on the healthcare system due to frequency of occurrence among most populations. A total of 130 patients with nasal fracture were included in this study; most included patients were male (83.1%). The mean age of patients was 28.5 years. The most frequent cause of nasal fracture was physical assault (54.6%), followed by road traffic accidents (20%). Most patients had epistaxis and presented with either active epistaxis at the time of assessment or epistaxis that spontaneously resolved after injury. Patients who had lacerations on the nose were more likely to have a displaced nasal bone. Isolated nasal bone fractures were more commonly noted in victims of physical assault, whereas combined facial bone fractures were commonly noted in patients involved in road traffic accidents. [27]

Anatomy

The nose is the most prominent and anterior facial feature; thus, it is most readily exposed to trauma. The nose is supported by cartilage on the dorsal and caudal aspects, and by bone posteriorly and superiorly. Paired nasal bones, the maxillary crest, and nasal bones, jutting from the frontal bone, form the bony framework that supports underlying nasal cartilages. The entire lower two thirds of the nose is cartilaginous.

Overlying the framework of the nose are soft tissues, including muscles, nerves, and mucous glands. The lower two thirds of the nose houses 2 upper lateral cartilages, which originate from underneath the inferior aspect of the nasal bones and project into the scroll region of the nose just superior to the nasal tip. Paired upper lateral cartilages are continuous with the dorsal nasal septum. The septum includes dorsal, caudal, posterior, and maxillary attachments among its components; this is often referred to as the quadrangular cartilage. The lower lateral crura are composed of medial, intermediate, and lateral crural components. The medial crura are attached to the septum with adhesive ligaments at the caudal septum, giving structural support to the nasal tip, which represents the transition between intermediate and lateral crura.

Nasal bones are the most commonly fractured in the human body. In most uncomplicated cases, closed reduction under local and topical anesthesia or general anesthesia produces a satisfactory return to pretraumatic nasal function and appearance. Timing is a critical consideration when these fractures are addressed, because of the tendency of bone fragments to fixate in their posttraumatic locations if left in place longer than 10-14 days and because of the difficulty associated with closed reduction in the edematous nose if attempted before 3 -5 days have passed since the injury. [2]

Classification of nasal trauma

Nasal fractures can be classified on a scale that stratifies the severity of the injury. An isolated nasal bone fracture is usually caused by low-velocity trauma. If the nose is fractured by high-velocity trauma, facial fractures are more likely to occur concurrently. [2]

-

Type I: Injury limited to soft tissue

-

Type IIa: Simple, unilateral nondisplaced fracture

-

Type IIb: Simple, bilateral nondisplaced fracture

-

Type III: Simple displaced fracture

-

Type IV: Closed comminuted fracture

-

Type V: Open comminuted fracture or complicated fracture

Limitations of techniques

Use of plain images and CT scans for diagnosis and management of nasal fractures has been controversial. Several small studies have shown that these modalities are neither cost-effective nor beneficial for the patient or the physician. Nasal fractures are usually evident and can be identified by means of careful history-taking and physical examination. Rarely is radiologic confirmation of these injuries needed. [28] However, some clinicians continue to use plain images and CT scans, and the radiologist must understand the diagnostic pitfalls to reduce the rate of erroneous readings. [29, 30]

Wexler opined that nasal radiographs were a medicolegal necessity and considered them an important adjunct in acute injuries to nasal bones. [31] Unfortunately, this opinion was not founded on solid experimental data. The practice of ordering unnecessary radiographs encourages poor patient care and devalues the importance of thorough history-taking and physical examination. This practice also leads to needless irradiation, increased expense, and wasted time. [32, 33, 34, 35, 36]

Pérez-García and associates investigated the use of endonasal infiltrative anesthesia for management of pain associated with nasal bone fracture reduction. Fifty-two patients with nasal bone fracture were distributed into 2 groups. In the first group, topical endonasal anesthesia and external transcutaneous infiltrative anesthesia were employed. In the second group, endonasal infiltrative anesthesia was added. Visual analog scale pain scores related to different steps of the procedure were registered. The addition of endonasal infiltrative anesthesia was associated with a significant decrease in pain during reduction maneuvers (6.71 vs 4.83) and nasal packing (5.18 vs 3.46). Data show that added endonasal infiltrative anesthesia provides an effective method of pain reduction during nasal bone fracture treatment. [37]

Pediatric patients pose additional challenges, and their procedures should ideally be performed under general anesthesia. Most type IIa to type IV fractures in adults can be successfully reduced with a combination of topical and infiltrative local anesthesia. Ideally, closed reduction is performed 5-7 days post injury to allow most of the edema to resolve and to facilitate palpation and manipulation of bony fragments. [2] When one wishes to limit exposure of children to radiation, ultrasonography is helpful in evaluating nasal fracture, septal deviation, and level of comminution. This can be accomplished with a 7- to 15-MHz linear array transducer. [38]

Radiography

Waters view

The Waters (occipitomental) view is perhaps the best overall for observing facial fractures in general. Radiography is performed with the patient in the posteroanterior position and with the canthomeatal line at an angle of approximately 37° relative to the surface of the film. The patient's dentures and oral prosthetic devices, if any, should be removed because these structures may cause interference.

(See the image below.)

Nasal fracture. Posteroanterior view shows displaced septum from the maxillary crest and a deviated nasal root to the patient's right.

Nasal fracture. Posteroanterior view shows displaced septum from the maxillary crest and a deviated nasal root to the patient's right.

The Waters view reveals orbits, maxillae, zygomatic arches, dorsal pyramid, lateral nasal walls, and septum. The radiologist should look for abnormalities of the nasal septum and arch, keeping in mind areas of relative weakness. Marked deviation, displacement with sharp angulation, and soft tissue swelling are signs of possible fracture. Soft tissue edema can be sufficient to obscure the extent of a fracture.

Other structures such as frontal, maxillary, and ethmoid sinuses may also be involved. Any such involvement should alert the physician to the possibility of concomitant fractures. Some have found that coronal sutures can mimic nasal fractures because sutures can become superimposed over the nasal bones. [39]

(See the images below.)

Nasal fracture. Waters view shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Nasal fracture. Waters view shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Nasal fracture. Waters view (close-up view of the patient in the previous image) shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Nasal fracture. Waters view (close-up view of the patient in the previous image) shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

Lateral view

The lateral view (profilogram) is obtained with the infraorbitomeatal line parallel to the transverse axis of the film and the intrapupillary line perpendicular to the plate. This orientation provides a true lateral projection that is neither tilted nor rotated; therefore, paired structures are superimposed. Many prefer to include the full profile from the forehead to the chin by selecting a technique that uses a Bucky grid. [40]

(See the image below.)

Nasal fracture. Lateral nasal images placed back to back. Notice the dorsal deformity of the nasal bones and the small lucent lines that pass all the way through the nasal bones. Short, lucent lines that reach the anterior cortex of the nasal bone, with or without displacement, should be regarded as nasal fractures.

Nasal fracture. Lateral nasal images placed back to back. Notice the dorsal deformity of the nasal bones and the small lucent lines that pass all the way through the nasal bones. Short, lucent lines that reach the anterior cortex of the nasal bone, with or without displacement, should be regarded as nasal fractures.

Fractures of nasal bones are frequently transverse. The lateral view obtained when a soft tissue technique is used is probably best for depicting old and new fractures of nasal bones. The profilogram provides no information regarding a possible laterally displaced nasal bone. [22, 40] Short, lucent lines that reach the anterior cortex of the nasal bone, with or without displacement, should be regarded as a fracture. [32] Evaluation of air zones by profilogram can provide important information because air zones commonly are lost after trauma. Alterations in air zone shapes may indicate increased cartilage volume or a septal hematoma. [40]

Other lines such as normal sutures or longitudinally oriented nasociliary grooves can be mistaken for longitudinal fractures. However, a nasociliary groove should never cross the plane of the nasal bridge; if such crossing is detected, the line is a fracture. Fortunately, fractures usually reveal sharpened delineation with greater lucency when compared with normal sutures and grooves. [26] The radiologist must look closely for marked deviation, displacement with sharp angulation, and soft tissue swelling.

It is important to remember that only approximately 15% of old fractures heal by ossification; as a result, old fractures are easily mistaken for new fractures, and this increases the rate of false-positive readings. [34]

Degree of confidence

Radiographic findings consistent with nasal fracture may be identified in 53-90% of patients with isolated nasal fracture. [36] Because of this and other concerns, researchers have questioned the reliability of nasal bone radiographs. [34]

Logan and coworkers believed that the high percentages of false-negative and false-positive results with nasal bone radiographs had several causes. Old fractures, vascular markings, cartilage fractures, midline nasal sutures, nasomaxillary sutures, and thinning of the nasal wall represent a few of the many features that may mislead even an experienced radiologist. These authors reported a true-positive rate of 86% and a false-positive rate of 8%. [34] De Lacey and associates conducted a similar study, which showed that 66% of control subjects had a false-positive reading when Waters view radiographs were obtained. [32]

Computed Tomography

CT scans are usually obtained when another traumatic facial or skull fracture is suspected. Many fractures are detected on routine head CT scans in patients with trauma. Although CT scans can be used to show the extent of nasal injury, they are rarely required. Contiguous, thin (2-3 mm), axial and coronal sections with bone windows must be obtained; however, axial images can be used to reconstruct coronal planes. These scans are helpful when associated injuries are suspected in combination with nasal fracture. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

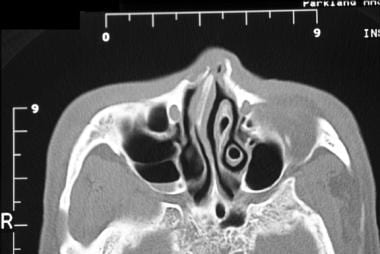

(CT scans of nasal fractures are shown below.)

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones. Note the septal involvement.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones. Note the septal involvement.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

CT scans depict important structures such as orbital walls, zygomatic arches, frontozygomatic sutures, maxillary buttresses, ethmoid air cells, nasal bones, dorsal pyramid, and the floor of frontal sinuses with associated nasofrontal ducts. Nasal fractures that have recently occurred are usually easily recognized on CT; however, as with plain radiographs, old fractures and normal sutures may be mistaken for new fractures.

Lim and associates examined postoperative changes in 128 patients after closed reduction of nasal fracture by analyzing findings on CT scans immediately and at 3 months postoperatively in patients with pure nasal bone fracture. The overall success rate was 49.2%. At 3 months postoperatively, 33 cases exhibited improvement to a higher grade, and 25 cases improved from an unacceptable outcome to a successful outcome, with an overall success rate of 70.3%. [10]

Ultrasonography

Computed tomography (CT) has greater sensitivity than ultrasonography, but research has shown that ultrasonography may have good specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for midline nasal fractures. [41]

Ultrasonography can show local and superficial fractures of the nasal bone. However, it is difficult to see the whole nasal bone with this modality. Shigemura and associates used water as a coupling medium for ultrasonography in 76 nasal bone fracture cases and found that they could obtain clear images of the entire nasal bone and surrounding bones with this technique. However, some images revealed artifacts and blurred areas. They noted that this method can provide whole clear images of the nasal bone and surrounding bones in a single field. They found that almost all artifacts and blurred images revealed by this method could be avoided by making some small changes—for example, tilting the probe, pouring the water slowly, and moving the probe closer to the nose. [42]

-

Nasal fracture. Posteroanterior view shows displaced septum from the maxillary crest and a deviated nasal root to the patient's right.

-

Nasal fracture. Waters view shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

-

Nasal fracture. Waters view (close-up view of the patient in the previous image) shows a deviated nasal septum, a quadrangular cartilage displaced from the maxillary crest, and a nasal root deviated to the right.

-

Nasal fracture. Lateral nasal images placed back to back. Notice the dorsal deformity of the nasal bones and the small lucent lines that pass all the way through the nasal bones. Short, lucent lines that reach the anterior cortex of the nasal bone, with or without displacement, should be regarded as nasal fractures.

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 48 hours after an assault, with complaints of right eye pain, nasal airway obstruction, and deformity. Note the asymmetry of the nasal bones and the dorsal nasal column.

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 48 hours after an assault, with complaints of right eye pain, nasal airway obstruction, and deformity (same patient as in the previous image).

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 48 hours after an assault, with complaints of right eye pain, nasal airway obstruction, and deformity (same patient as in the previous 2 images).

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 2 weeks after nasal osteotomies and closed nasal reduction, which were performed after an assault (same patient as in the previous 3 images). The patient had multiple previous nasal fractures and refused open septorhinoplasty. Note the broad nasal dorsum.

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 2 weeks after nasal osteotomies and closed nasal reduction, which were performed after an assault (same patient as in the previous 4 images). The patient had multiple previous nasal fractures and refused open septorhinoplasty.

-

Nasal fracture. Patient presenting 2 weeks after nasal osteotomies and closed nasal reduction, which were performed after an assault (same patient as in the previous 5 images). The patient had multiple previous nasal fractures and refused open septorhinoplasty. Note the broad nasal dorsum.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture has occurred in the weaker lower portion of the nasal bones. Note the septal involvement.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

-

Nasal fracture. Coronal CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that a portion of the nasal bones is involved.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the right. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is severely deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. Axial CT scan shows a nasal fracture with root deviation to the left. Note that the fracture involves the septum as well, and that the septum is deviated.

-

Nasal fracture. This patient presented to the emergency department 6 hours after an aggravated assault. Note the obvious dorsal column flattening and deviation. The patient had no associated facial fractures, but because of high suspicion for other fractures, a CT scan was obtained.

-

Nasal fracture. This patient presented to the emergency department 6 hours after an aggravated assault (same patient as in the previous image). Note the obvious nasal deviation and the flattened nasal dorsum.

-

Nasal fracture. This patient presented to the emergency department 6 hours after an aggravated assault (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Note the obvious nasal deformity.

-

Nasal fracture. This patient presented to the emergency department 6 hours after an aggravated assault (same patient as in the previous 3 images). Note the obvious nasal deformity.

-

Nasal fracture. Image was obtained 7 days after septoplasty and nasal osteotomies (same patient as in the previous 4 images).

-

Nasal fracture. Image was obtained 7 days after septoplasty and nasal osteotomies (same patient as in the previous 5 images).

-

Nasal fracture. Image was obtained 7 days after septoplasty and nasal osteotomies (same patient as in the previous 6 images).