Overview of Male Breast Cancer

The etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer in males is similar to that in females. Unlike breast cancer in females, however, breast cancer in men is rare. Although its frequency has increased in recent decades—particularly in the urban United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom—breast cancer in males accounts for only about 1% of breast cancers. [1, 2, 3] In the United States, males are expected to account for only 2800 of the estimated 319,750 cases of breast cancer predicted to occur in 2025. [4]

Unfortunately, this rarity has largely precluded prospective randomized clinical trials. Lack of awareness that men develop breast cancer may also contribute to the infrequency of early diagnosis. Men tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at an older age than women and with a more advanced stage of disease: more than 40% of patients have stage III or IV disease at diagnosis.

A study by Wang et al using the National Cancer Database reported higher breast cancer mortality in men than in women across all stages of the disease, with overall survival of 45.8% in men versus 60.4% in women, and 5-year survival of 77.6% versus 86.4%, respectively. Adjustment for clinical characteristics, treatment factors, age, race/ethnicity, and access to care did not eliminate those disparities; the authors suggested that other factors (eg, additional biological attributes, treatment compliance, lifestyle) might be responsible. [5]

See the image below.

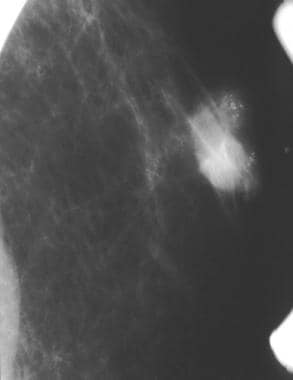

A partially circumscribed retroareolar mass in a male with suspicious microcalcifications; this is known breast cancer.

A partially circumscribed retroareolar mass in a male with suspicious microcalcifications; this is known breast cancer.

For more information, see the following:

Etiology

Environmental and genetic risk factors for male breast cancer have been identified. Male breast cancers are reported to be associated with the following [6, 7, 8] :

-

Older age (mean age at diagnosis is 60-70 years, although young men may be affected)

-

Carriage of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

-

Family history of breast cancer

-

Thoracic radiation therapy

-

Klinefelter syndrome

-

Gynecomastia

-

Cirrhosis

-

Overweight and obesity

-

History of testicular pathology

The family history is positive for breast cancer in approximately 30% of male breast cancer cases. A familial form of breast cancer is seen in which both sexes are at increased risk for breast cancer. A review of data from 3184 BRCA1 and 2157 BRCA2 families in the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 documented elevated risk of male breast cancer in carriers of pathogenic variants of BRCA1 (relative risk [RR] 4.30), and especially of pathogenic variants of BRCA2 (RR = 44.0). [9] Other studies have found that men who carry BRCA2 mutations are at 80-fold higher risk of developing breast cancer compared with men in the general population, that breast cancer develops in up to 1 in 10 male BRCA2 carriers, and these cases may be more aggressive than sporadic cases. [10]

In a review of germline multi-gene panel testing (MGPT) in 715 male breast cancer patients, 18.1% tested positive for variants in 16 breast cancer susceptibility genes. BRCA2 and CHEK2 were the most frequently mutated genes (in 11.0 and 4.1% of patients, respectively) and pathogenic variants in BRCA2, CHEK2, and PALB2 were associated with significantly increased risk. Average age at diagnosis was 54 years in patients with CHEK2 1100delC, compared with 62 years in patients without pathogenic variants and 64 years in carriers of all other pathogenic variants. Pritzlaff et al suggest offering MGPT to all male breast cancer patients. [11]

Klinefelter syndrome is the strongest risk factor, although rates in those with the syndrome are still far lower than rates in women. Possible mechanisms may involve decreased micro-RNA expression and increased estrogen/progesterone receptor expression. [12]

Exogenous hormone therapy, such as treatment for prostate cancer, is not associated with an increased risk of male breast tumors. No association with smoking history has been reported. Meta-analysis of epidemiology of male breast cancer failed to reveal any clear association with other potential risk factors such as reproductive history, education, various diseases, or exposure to drugs. Case-control studies on this subject have been confounded by small numbers or contradictory results.

Overall, male breast cancer shares risk factors associated with female breast cancers, especially high estrogen levels. A Dutch review of breast cancer in transsexual people found that in transsexual women (male sex assigned at birth, female gender identity), risk of breast cancer was 46-fold higher than in cisgender men, but lower than in cisgender women. In transsexual men (female sex assigned at birth, male gender identity), breast cancer risk was lower than expected compared with cisgender women. [13]

These epidemiologic factors, in addition to studies suggesting that men with breast cancer have elevated estriol production, indicate a relationship between male breast cancer and hormones in addition to the well-established relationship with genetics.

Diagnosis

Male breast cancer usually presents as a painless lump. In 75% of cases, the lump is a hard and fixed nodule in the subareolar region, with nipple involvement more common than in women. [14] Other local signs include the following [6, 8] :

-

Nipple retraction, bleeding, discharge, or pain

-

Skin erythema, flaking, ulceration, or peau d’orange

-

Palpable axillary adenopathy

In patients with clinical features completely consistent with gynecomastia or pseudogynecomastia (overgrowth of glandular breast tissue or excess fat deposits, respectively), breast cancer may be excluded on clinical grounds, and no further evaluation may be necessary (see Gynecomastia for description of the clinical findings in such cases). [15] If findings are equivocal, however, imaging studies can be useful in diagnosis. [2] The American College of Radiology recommends the following approach to imaging in men with breast symptoms [15] :

-

If an indeterminate breast mass is identified, the initial recommended imaging study varies by patient age: ultrasound in men younger than age 25 years; mammography or digital breast tomosynthesis in men age 25 years and older.

-

If physical examination is suspicious for breast cancer, mammography or digital breast tomosynthesis is recommended irrespective of patient age

Ultrasound

Ultrasound features of male breast cancer are similar to those of female breast cancer. Masses that are taller than wide (antiparallel) and hypoechoic are worrisome. The margins are angulated, microlobulated, or spiculated. [16, 17]

Similar sonographic findings may be observed in gynecomastia or inflammation; therefore, ultrasonography alone is not a reliable method to distinguish male breast cancer from other etiologies. Abscesses, sebaceous cysts, gynecomastia, and fat necrosis may all give false positives.

Evaluation of axillary lymph nodes is important if there is high clinical suspicion for breast cancer. Abnormal lymph nodes with an absent fatty hilum and asymmetric cortical thickness are suspicious for regional metastatic disease.

Mammography

On mammography, male breast cancer is typically retroareolar as it arises from the central ducts. Gynecomastia will always originate in a subareolar position, although the distribution may extend away from the nipple. An asymmetry with the morphology of gynecomastia that does not involve the subareolar breast is thus suspicious.

Masses are most commonly high density with an irregular shape. [16] Margins are usually spiculated, lobulated, or microlobulated.

Calcifications are observed less commonly than in female breast cancer and, when found, are coarser in appearance. Benign breast calcifications in men are uncommon, with the exception of vascular calcifications and fat necrosis.

Mammography is highly sensitive and specific for breast cancer in men, but it should be used to complement the clinical examination. Cases of carcinoma have been found by ultrasonography after they were obscured on previous mammograms by gynecomastia. [18]

Bilateral mammography should always be obtained to help in the evaluation of the baseline breast architecture. Almost all cases of gynecomastia will be bilateral, although typically asymmetric; thus, comparison with the contralateral side can aid in differentiating breast cancer from gynecomastia.

Histology

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy can confirm the diagnosis. [19] Histologically, the majority of breast cancers in men are ductal carcinoma in situ or infiltrating ductal carcinomas, but the entire spectrum of histologic variants of breast cancer has been seen, including papillary carcinoma and lobular carcinoma (although lobular carcinoma is extremely rare except in cases of estrogen exposure). [20] Most male breast cancers (~80%) are hormone receptor positive, 15% overexpress human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and 4% are triple negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 negative). [21]

Treatment & Follow-up

Treatment of male breast cancer comprises surgery, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy. [6] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a draft guidance encouraging the inclusion of male patients in breast cancer clinical trials, noting that many treatments are approved for women only and further data may be necessary to support approval for use in men. [22]

Surgery

The general principles of surgical management of male breast cancer are similar to those of breast cancer in women. Simple mastectomy remains the usual choice for T1 and T2 breast tumors. Nipple- and skin-sparing mastectomy are common in women, but generally not practiced in male breast cancer. Cosmetic outcomes are of secondary concern, but where feasible, surgeries with better cosmetic outcomes can be considered in men as well. As in women, sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed in male patients with a clinically node-negative axilla. [16, 23]

Retrospective studies indicate that breast-conserving surgery can be performed in carefully selected patients, with outcomes equivalent to mastectomy. [24, 25] For T1 and T2 breast cancer, breast-conserving surgery may be the preferred approach, as it offers similar rates of 5-year overall survival and local recurrence, and lower rates of postoperative complications, compared with mastectomy. [26] Male breast cancer patients who present with locally advanced tumors (ie, T3, T4) can be offered therapy similar to that for locally advanced breast cancer in women, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection.

Radiation therapy

Principles of radiation therapy are same as in breast cancer in women. No randomized controlled studies have evaluated radiation therapy in men with breast cancer; instead, the recommendations are based on evidence derived from data from clinical trials in women. One difference is that most expert opinion suggests a lower threshold for recommending radiation therapy in men than in women, due to the anatomy of the male breast. The typical indication for adjuvant radiation includes T3 or higher tumor stage, four or more positive lymph nodes, and positive surgical margins.

A review of 539 cases of stage IV male breast cancer found that in estrogen receptor–positive cases, treatment with surgery, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy (trimodality therapy) offered a survival benefit compared with surgery and systemic therapy. Five-year overall survival rates were 40% with trimodality therapy, versus 27% with surgery plus systemic therapy (P < 0.002). [27]

Systemic therapy

Recommendations for use of systemic therapy in male breast cancer are generally the same as in female breast cancer, because the rarity of male breast cancer has precluded the performance of clinical studies. Tamoxifen is the recommended adjuvant endocrine therapy. Duration is at least 5 years and in appropriate patients can be extended to 10 years, given the results of the Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Longer Against Shorter (ATLAS) trial. [28]

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines recommend offering tamoxifen to men with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer who are candidates for adjuvant endocrine therapy. The initial treatment duration is 5 years; men who have completed 5 years of tamoxifen, have tolerated therapy, and still have a high risk of recurrence may be offered an additional 5 years of tamoxifen therapy. [29]

Data are limited regarding the use of aromatase inhibitors in men. A retrospective study indicates that aromatase inhibitors may be associated with poorer outcomes in men when compared with tamoxifen. The overall survival (OS) of tamoxifen-treated female and male patients had similar 5-year OS, 85.1 and 89.2%, respectively (P = 0.972). Notably, in patients treated with an aromatase inhibitor, 5-year OS was significantly greater in females than in males (85.0% versus 73.3%; P = 0.028). [30, 31]

ASCO guidelines recommend that men with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer who are candidates for adjuvant endocrine therapy but have a contraindication to tamoxifen may be offered a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist/antagonist and an aromatase inhibitor. [29] National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines also advise that when an aromatase inhibitor is used in men, a GnRH analog should be given concurrently. [25]

In addition, NCCN guidelines note that available data suggest single-agent fulvestrant has similar efficacy in men as in women. Although newer agents such as CDK4/6 inhibitors (in combination with an aromatase inhibitor or fulvestrant), mTOR inhibitors, and PIK3CA inhibitors have not been systematically evaluated in clinical trials in men with breast cancer, the NCCN considers it reasonable to recommend these agents to men with advanced breast cancer, based on extrapolation of data from studies comprised largely of women. Use of chemotherapy, HER2-targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for advanced breast cancer mirrors the use of those agents in women. [25]

ASCO guidelines recommend that men with advanced or metastatic, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer should be offered endocrine therapy as first-line therapy, except in cases of visceral crisis or rapidly progressive disease. Options include tamoxifen, an aromatase inhibitor plus a GnRH agent, and fulvestrant. CDK4/6 inhibitors can be used in men as they are used in women. Those men who exprience a recurrence of metastatic, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer while receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy should be offered an alternate endocrine therapy, except in cases of visceral crisis or rapidly progressive disease. [29]

ASCO guidelines also recommend that targeted therapy guided by HER2, PDL-1, PIK3CA, and germline BRCA mutation status may be used in the treatment of advanced or metastatic male breast cancer, using the same indications and combinations that are offered to women. Management of endocrine therapy toxicity is similar to the approach used for women. [29]

Palbociclib, a cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) inhibitor, gained FDA approval in 2109 for treatment of men with breast cancer. It is indicated for treatment of adults with hormone receptor–positive/HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer in combination with an aromatase inhibitor as initial endocrine-based therapy in men or postmenopausal women, or in combination with fulvestrant in patients with disease progression following endocrine therapy. For men treated with combination palbociclib plus aromatase inhibitor therapy, consider treatment with a luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist. [25, 32]

The CDK inhibitor ribociclib gained FDA approval for use in men with breast cancer in 2021. It is indicated in combination with fulvestrant as initial endocrine-based therapy or following disease progression on endocrine therapy. [33]

Most cases of metastatic male breast cancer are estrogen receptor (ER)–positive, and guidelines from the European School of Oncology and the European Society for Medical Oncology recommend endocrine treatment with tamoxifen as the preferred option for these patients, unless they have suspected or proven endocrine resistance or rapidly progressive disease that requires a fast response. [34] Second-line hormonal approaches include orchiectomy, aromatase inhibitors, and androgen ablation. [35] However, chemotherapy can also provide palliation.

Long-term monitoring

Men who have had breast cancer are at increased risk for a second ipsilateral or contralateral breast cancer, as well as for second primary colorectal, pancreatic and thyroid cancers. [36, 37] The risk of breast cancer recurrence continues beyond 15 years after primary treatment. The risk of subsequent cancers is highest in men who were younger than 50 years when their initial cancer was diagnosed. Thus, periodic screening is probably advisable. The NCCN notes that only limited data support screening for breast cancer in men. [25]

ASCO guidelines include the following recommendations regarding follow-up [29] :

-

Patients should be counseled about the symptoms of breast cancer recurrence, including new lumps, bone pain, chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, or persistent headaches.

-

Continuity of care for patients with breast cancer is recommended and should be performed by a physician experienced in the surveillance of patients with cancer and in breast examination, including the examination of irradiated breasts.

-

Men with a history of breast cancer treated with lumpectomy should be offered ipsilateral annual mammography if technically feasible, regardless of genetic predisposition.

-

Men with a history of breast cancer and a genetic predisposing mutation may be offered contralateral annual mammography.

-

Breast magnetic resonance imaging is not routinely recommended in men with a history of breast cancer.

-

Male patients with breast cancer should be offered genetic counseling and genetic testing for germline mutations

In men with early-stage breast cancer who receive adjuvant GnRH analog therapy, NCCN guidelines recommend bone density assessment at baseline and every 2 years. Low bone density in those patients should be managed according to standard guidelines. [25]

-

A partially circumscribed retroareolar mass in a male with suspicious microcalcifications; this is known breast cancer.