Practice Essentials

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) account for less than 1% of GI tumors, but they are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the GI tract. [1] GISTs are usually found in the stomach or small intestine but can occur anywhere along the GI tract and rarely have extra-GI involvement. See the image below.

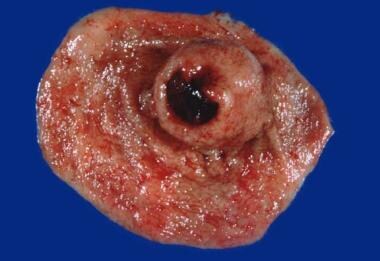

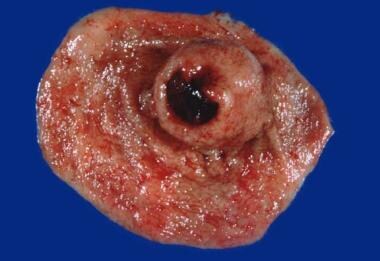

Shown here is a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This is a gross specimen following partial gastrectomy. Note the submucosal tumor mass with the classic features of central umbilication and ulceration.

Shown here is a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This is a gross specimen following partial gastrectomy. Note the submucosal tumor mass with the classic features of central umbilication and ulceration.

Signs and symptoms

Up to 75% of GISTs are discovered when they are less than 4 cm in diameter and are either asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms. They are frequently diagnosed incidentally during radiologic studies or endoscopic or surgical procedures performed to investigate the GI tract disease or to treat an emergent condition such as hemorrhage, obstruction, or perforated viscus. Clinical manifestations of GISTs are as follows:

-

Vague, nonspecific abdominal pain or discomfort (most common)

-

Early satiety or a sensation of abdominal fullness

-

Palpable abdominal mass (rare)

-

Malaise, fatigue, or exertional dyspnea with significant blood loss

-

Focal or widespread signs of peritonitis (with perforation)

Obstructive signs and symptoms of GISTs can be site-specific, as follows:

-

Dysphagia with an esophageal GIST

-

Constipation and a distended, tender abdomen with a colorectal GIST

-

Obstructive jaundice with a duodenal GIST

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

No laboratory test can specifically confirm or rule out the presence of

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) account for less than 1% of GI tumors, with only about 5000 new cases expected annually in the United States. GISTs rank a distant third in prevalence behind adenocarcinomas and lymphomas among the histologic types of GI tract tumors. However, GISTs are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the GI tract. See the image below.

Shown here is a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This is a gross specimen following partial gastrectomy. Note the submucosal tumor mass with the classic features of central umbilication and ulceration.

Shown here is a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This is a gross specimen following partial gastrectomy. Note the submucosal tumor mass with the classic features of central umbilication and ulceration.

GISTs are usually found in the stomach or small intestine but can occur anywhere along the GI tract. Rarely, GISTs have extra-GI involvement. [5]

Historically, these lesions were classified as leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas because they possessed smooth muscle features when examined under light microscopy. In the 1970s, electron microscopy found little evidence of smooth muscle origin of these tumors. In the 1980s, with the advent of immunohistochemistry, it was shown that these tumors did not have immunophenotypic features of smooth muscle cells and rather expressed antigens related to neural crest cells. Mazur and Clark in 1983, and Schaldenbrand and Appleman in 1984, were the first to describe "stromal tumors" as a separate entity.

According to the work of Kindblom and associates, reported in 1998, the actual cell of origin of GISTs is a pluripotential mesenchymal stem cell programmed to differentiate into the interstitial cell of Cajal. [6] These are GI pacemaker cells found in the muscularis propria and around the myenteric plexus and are largely responsible for initiating and coordinating GI motility. This finding led Kindblom and coworkers to suggest the term GI pacemaker cell tumors. [6]

Additional studies found that interstitial cells of Cajal express KIT and are developmentally dependent on stem cell factor, which is regulated through KIT kinase. Perhaps the most critical development that distinguished GISTs as a unique clinical entity was the discovery of c-KIT proto-oncogene mutations in these tumors in by Hirota and colleagues in 1998. [7]

Activating KIT mutations are seen in 85-95% of GISTs. About 3-5% of the remainder of KIT-negative GISTs contain PDGFR-alpha mutations. [8, 9, 10]

The PDGFR alpha mutation seems to leave the PDGFRalpha receptor constitutively active and may represent an alternate pathway with activation of similar downstream signaling as the KIT receptor. The discovery of these receptor mutations has redefined the classification and management of the disease.

The discovery in 2000 that the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib, initially used to treat chronic myeloid leukemia, is effective in treating metastatic GISTs revolutionized the care of patients with GISTs. [11] Imatinib has been shown to target KIT and PDGFR alpha in KIT receptor-positive GIST. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

This discovery has been celebrated as the example of the power of targeted, individualized therapy and has helped focus a great deal of attention on this orphan disease. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved imatinib for treatment of metastatic GIST in 2002 and for the adjuvant therapy of primary resected GIST in 2008. [5] The FDA has also approved the newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib and regorafenib for treatment of GISTs that are unresponsive to imatinib.

Pathophysiology

GISTs are typically diagnosed as solitary lesions, although in rare cases (ie, pediatric type), multiple lesions can be found. These tumors have been reported to range in size from smaller than 1 cm to as large as 40 cm in diameter. [17] GISTs can grow intraluminally or extraluminally toward adjacent structures. When the growth pattern is extraluminal, patients can harbor the disease symptom free for an extended period and present with very large exogastric masses.

Approximately 50-70% of GISTs originate in the stomach. Of those, 15% occur in the cardia and fundus, 70% in the body, and 15% in the antrum). [18] The small intestine is the second most common location, with 20-30% of GISTs arising from the jejunoileum. Less frequent sites of occurrence include the colon and rectum (5-15%) and esophagus (< 5%). Primary pancreatic, omental, or mesenteric GISTs have been reported but are very rare. [19]

Distant metastases tend to appear late in the course of the disease in most cases. In contrast to other soft tissue tumors, the common metastatic sites of GISTs are the liver and peritoneum. Lymph node involvement is rare, occurring in only 0-8% of cases. However, in rare cases of pediatric GIST, lymph nodes are commonly involved, and distant metastasis is present at diagnosis. [20] Despite these metastases, these variant GISTs have an indolent clinical course.

Etiology

Most GISTs are associated with gain-of-function mutations in exon 11 of the c-kit proto-oncogene., which encodes the transmembrane tyrosine kinase KIT. [21] The c-kit proto-oncogene is located on chromosome arm 4q11-12. Most of these mutations are of the in-frame type, which allows preservation of c-kit expression and activation.

Stem cell factor, also called Steel factor or mast cell growth factor, is the ligand for KIT. Under normal circumstances, KIT activation is initiated when stem cell factor binds to the extracellular domain of c-Kit. The result is homodimerization of the normally inactive c-Kit monomers. Autophosphorylation of intracellular tyrosine residues then occurs, exposing binding sites for intracellular signal transduction molecules.

What follows is activation of a signaling cascade that involves phosphorylation of several downstream target proteins, including MAP kinase, RAS, and others. Ultimately, the signal is transduced into the nucleus, resulting in mitogenic activity and protein transcription.

In the majority of GISTs, KIT is constitutively phosphorylated and does not require stem cell factor for initiation of the sequence of c-Kit homodimerization and autophosphorylation. This is termed ligand-independent activation. The increased transduction of proliferative signals to the nucleus favors cell survival and replication over dormancy and apoptosis, leading to tumorigenesis. [22]

Although 95% of GISTs are KIT positive, 5% of GISTs have no detectable KIT expression. In a proportion of these KIT-negative GISTs, mutations occur in the PDGFRA gene rather than KIT. Immunostaining with PDGFRA has been shown to be helpful in discriminating between KIT-negative GISTs and other gastrointestinal mesenchymal lesions.

BRAF mutations and protein kinase C theta (PKCtheta) have also been reported in a small proportion of GISTs lacking KIT/PDGFRA. Initial studies suggest that GISTs from BRAF mutations have a predilection for the small bowel and are not associated with a high risk of malignancy. [23] Mutations of the NF2 gene have also been reported in GISTs, but these mutations do not seem to be an integral part of GIST pathogenesis. [24]

A small minority of GISTs are associated with hereditary syndromes. Familial GISTs are characterized by inherited germline mutations in KIT or PDGFRA and additional findings such as the following:

-

Cutaneous hyperpigmentation

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

-

Dysphagia

-

Diverticular disease

Of individuals with these germline mutations, 90% may develop GISTs by 70 years of age. Patients with germline autosomal dominant mutations of KIT may present with multiple GISTs at an early age. [25] However, familial GISTs have favorable outcomes and do not appear to be associated with shortened survival. No data support preventive therapy in patients with these germline mutations.

In addition, the following syndromes are linked to GISTs [25] :

-

Carney triad - gastric GISTs, paraganglioma, and pulmonary chondromas (these may occur at different ages); primarily affects young women [26]

-

Carney-Stratakis syndrome - GIST and paraganglioma

-

Neurofibromatosis type 1 - Wild-type, often multicentric GIST, predominantly located in the small bowel

Epidemiology

Frequency

Roughly 5000 new cases of GISTs are diagnosed annually in the United States. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the annual age-adjusted incidence of GISTs rose from 0.55 per 100,000 population in 2001 to 0.78/100,000 in 2011. [27]

Data on worldwide frequency are limited, but in general, GISTs constitute 1-3% of all gastric malignancies. Population-based studies from Iceland, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden report annual incidence rates ranging from 6.5 to 14.5 cases per million. [28, 29, 30, 31]

Mortality/Morbidity

According to 2001-2011 SEER data, 5-year overall survival rates for patients with GISTs are 77% for those with localized disease at diagnosis, 64% for those with regional disease, and 41% for those with metastatic disease. [27]

Gastric GISTs carry a better prognosis than small bowel GISTs of similar size and mitotic rate. In general, gastric GISTs portend a much better prognosis than adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

Even after complete resection of primary GIST, at least 50% of patients develop recurrence or metastasis, at a median time to recurrence of 2 years. This high rate of recurrence is in the setting of an overall 5-year survival rate of 50%.

Larger GISTs are associated with complications such as GI hemorrhage, GI obstruction, and bowel perforation. Patients with advanced GISTs who are receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy may develop tumor-related intraluminal or intraperitoneal hemorrhage, rupture, fistula, or obstruction requiring emergent surgery.

Race-, Sex-, and Age-related Demographics

A review of the SEER database from 2001-2011 found that GISTs were more common in non-Hispanics than Hispanics (rate ratio [RR]=1.23) and in blacks (RR=2.07) or Asians/Pacific Islanders (RR=1.50) than in whites. GISTs were also more common in males than females (RR=1.35). The incidence of GISTs increased with age, peaking among 70-79 year olds. [27]

Older age at diagnosis, male sex, black race, and advanced stage at diagnosis were independent risk factors of worse overall survival, on multivariate analysis. Those characteristics, along with earlier year of diagnosis, were also independent risk factors of worse GIST-specific survival. [27]

Prognosis

GISTs manifest a wide variety of clinical behavior, from slow-growing indolent tumors to aggressive malignant cancers with the propensity to invade adjacent organs, metastasize to the liver, and recur locally within the abdomen. Clinical presentation provides the most overt evidence for distinguishing benign from malignant behavior. Histologic analysis of biopsy or operative specimens provides objective measures for diagnosis and helps predict clinical behavior.

The predominant prognostic factors in patients with GISTs include the size of the tumor, location of the tumor, and the mitotic rate. [32, 33, 34] To these may be added the ability or inability to achieve completely negative resection margins. The following characteristics appear to be the most predictive of aggressive behavior in GISTs:

-

Mitotic rate greater than 5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPFs)

-

Size larger than 5 cm and 10 cm, which pose moderate and high malignant potential, respectively [17]

-

Location (small bowel GISTs of comparable size and mitotic rate are generally more aggressive than gastric GISTs)

Because no standardized staging system exists for stromal tumors of the GI tract and most series are small and heterogeneous, comparison of the different published survival rates is difficult. However, various reports of 5-year survival rates after R0 resection for GISTs range from 32-93%. In large series, this rate is about 50-60%.

The median survival after palliative resection is about 10 months, with a 5-year survival rate as high as 10%. These rates improve with the addition of imatinib. [35, 36, 32, 33] The disparity between patients presenting with localized primary disease (median survival of 5 y) and those presenting with metastasis or recurrent disease (median survival of 10-20 mo) is large.

Unfortunately, no absolute determinations can be made because even small lesions with low mitotic rates can metastasize or behave in a locally aggressive fashion. In 2002, Fletcher and colleagues proposed the following classification system to define the risk of aggressive or malignant behavior in GISTs [37] :

-

Very low risk: size < 2 cm and < 5 mitoses/50 HPFs

-

Low risk: 2-5 cm and < 5/50 HPFs

-

Intermediate risk: < 5 cm and 6-10/50 HPFs or 5-10 cm and < 5/50 HPFs

-

High risk: >5 cm and >5/50 HPFs or >10 cm and any mitotic rate or any size and >10/50 HPFs

In 2009 Gold et al from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) developed a nomogram that uses tumor size, site, and mitotic index to predict relapse-free survival after resection of localized primary GIST. [38]

The NCCN criteria for risk stratification of primary GIST have not been incorporated into the AJCC staging but may be more helpful in determining individual risk for progressive disease, after margin-negative resection. The stratification is by mitotic index (≤5 versus >5 per 50 HPF) and then further divided by tumor size (≤2 cm vs >2 cm; ≤5 cm vs >5 cm; ≤10 cm vs >10 cm) and tumor location (gastric and non-gastric). [39]

Gastric GISTs greater than 10 cm but with an HPF mitotic index of 5/50 or less have only a 12% risk of progressive disease despite 34-52% risk of progressive disease in the other tumor locations. Gastric GISTs greater than 10 cm with a high mitotic index (>5/50 HPFs), however, have an equally high risk of progressive disease (86%) as GISTs in other locations (71-90%). [39]

Mutational status has both prognostic significance and impact on response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. In randomized clinical trials, the presence of a KIT exon 11 mutation was associated with better response, progression-free survival, and overall survival rates than KIT exon 9 mutant GISTs. The risk for progression and death were increased in patients with no detectable KIT or PDG-FRA mutations. [12]

Other factors found to have a negative impact on prognosis are as follows:

-

Tumor rupture during operation

-

Involvement of histologic margins

-

Lymph node involvement

In an analysis of 4,694 patients with localized GISTs from the National Cancer Data Base, Sineshaw and colleagues found that patients treated with adjuvant therapy had a 46% lower risk of death than patients treated with surgery alone, This survival benefit was significant for patients with GISTs larger than 10 cm. [40]

Patient Education

Patients should be educated about as many aspects of the disease as possible, including diagnostic and therapeutic measures and options. GIST Support International has produced a patient education booklet entitled Understanding Your GIST Pathology Report.

Most importantly, patients should be apprised of the need for lifelong close clinical follow-up, even after complete resection of disease. Emphasize that GISTs have a propensity to recur.

For patient education resources, see Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors.

-

Shown here is a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This is a gross specimen following partial gastrectomy. Note the submucosal tumor mass with the classic features of central umbilication and ulceration.

-

CT scan of the abdomen with oral contrast in a 60-year-old woman with a gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). A huge mass with central necrosis is observed originating from the gastric wall and narrowing its lumen. An ulcer crater can be identified within the mass (arrow).

-

Photomicrograph of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and magnified 40X. Note the solid sheet of spindle cells.

-

Photomicrograph of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and magnified 400X. This stromal tumor demonstrates spindle cells with epithelioid features.

-

Photomicrograph of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with immunohistochemical staining for CD117. Note the strong positive staining of tumor cells with negative staining of the adjacent vessel. Positive stain for CD117 is diagnostic of GIST.