Background

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt [1] (TIPS) creation is the percutaneous formation of a tract between the hepatic vein and the intrahepatic segment of the portal vein in order to reduce the portal venous pressure. The blood is shunted away from the liver parenchymal sinusoids, thus reducing the portal pressure. [2, 3, 4] TIPS, therefore, represents a first-line treatment for complications of portal hypertension, typically in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Indications

Accepted indications for TIPS include the following:

-

Uncontrolled variceal hemorrhage from esophageal, gastric, [5] and intestinal varices that do not respond to endoscopic and medical management [6]

-

Refractory ascites

-

Hepatic pleural effusion (hydrothorax)

Less well accepted indications for TIPS include the following:

-

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS)

-

Veno-occlusive disease (VOD)

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for TIPS include the following:

-

Severe and progressive liver failure (on the basis of the Child-Pugh score; scores A and B have a better outcome than score C)

-

Severe encephalopathy

-

Severe right-heart failure

Relative contraindications for TIPS include the following:

-

Portal and hepatic vein thrombosis

-

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

-

Active infection

-

Tumor within the expected path of the shunt

Outcomes

The technical success of TIPS placement is related to the experience and skill of the interventional radiologist. Data from three large centers (University of California, San Francisco; University of Pennsylvania; and the Freiberg group) demonstrated technical success rates higher than 90%.

Successful TIPS placement results in a portosystemic gradient of less than 12 mm Hg and immediate control of variceal-related bleeding. A target portosystemic gradient of 12 mm Hg is used; varices tend not to bleed if the gradient is less than 12 mm Hg. When technical failure occurs, it is usually due to an anatomic situation that prevents acceptable portal venous puncture. Significant reduction in ascites usually occurs within 1 month of the procedure, and this is estimated to occur in 50-90% of cases. [9, 10, 11]

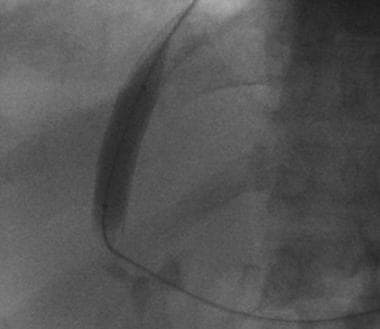

Late stenosis and occlusion are usually related to pseudointimal hyperplasia within the stent or, more commonly, intimal hyperplasia within the hepatic vein. In most cases, the stenotic stent can be crossed with a guide wire and recanalized with balloon dilation (see the image below) or repeat stent placement to improve long-term patency rates.

Primary patency after TIPS placement has been reported to be 66% after 1 year and 42% after 2 years. Primary-assisted patency rates at 1 and 2 years have been reported to be 83% and 79%, respectively, and secondary patency rates at 1 and 2 years have been reported to be 96% and 90%. [9]

Reported figures for 30-day mortality have varied among centers, and nearly all centers have reported few or no deaths directly related to the procedure itself. Early mortality has been shown to be related to the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score. Patients with severe systemic disease who have an APACHE II score higher than 20 are at greater risk for early mortality, compared with others.

Patients with active bleeding during the procedure also have increased early mortality. The 30-day mortality is in the range of 3-30%; the variation within this range is related to the preprocedural Child classification and to whether the procedure was performed on an emergency basis or an elective basis. [12] In 1995, LaBerge et al reported that cumulative survival rates in patients with Child grades of A, B, and C were 75%, 68%, and 49%, respectively, at 1 year and 75%, 55%, and 43%, respectively, at 2 years.

In a retrospective study that evaluated rebleeding rate, patency, mortality, and transplant-free survival in 286 cirrhotic patients receiving TIPS implantation for variceal bleeding (bare-metal stents, n = 119; polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]-covered stents, n = 167; median follow-up, 821 d), Bucsics et al found that the covered stents prevented variceal rebleeding more effectively than the bare-metal stents did, by virtue of their superior patency. [13] They recommended that only covered stents be implemented for bleeding prophylaxis when TIPS is indicated.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Ultrasound-guided puncture.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). CO2 angiography.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Pigtail for calibration.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Prestent portal and right atrial pressures.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Deploying of stent.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Deploying.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Poststent dilatation.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Dilatation post stenting.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Typical equipment kit.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Artist impression of stent in situ.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Curved catheter is placed into right hepatic vein.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Wedged hepatic venogram obtained by using digital subtraction technique obtained with CO2 gas demonstrates location of portal vein. Catheter is wedged in branch of right hepatic vein.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Image demonstrates advancement of Colapinto needle into right portal vein.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Portal venogram obtained with pigtail catheter shows filling of coronary vein.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Delayed venogram demonstrates filling of large varices.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. TIPS (10 X 68 mm Wallstent dilated with 10 mm X 4 cm balloon) has been placed. Note flow through Wallstent and filling of splenorenal shunt. Intrahepatic portal flow became reversed after TIPS placement.

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Basic procedure. Coil embolization of splenorenal shunt has been performed.

-

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) thrombosis. Image obtained after placement of initial TIPS shows good flow through shunt.

-

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) thrombosis. Sonogram obtained on day after shunt placement demonstrates thrombosis. Catheter was placed through thrombosed TIPS without any difficulty. Note absence of flow through shunt and hepatopetal portal flow.

-

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) thrombosis. After recanalization of shunt, Wallgraft is placed within it.

-

Early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) thrombosis. Good flow is restored through TIPS after placement of Wallgraft.

-

Parallel transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) required in this patient to effectively decrease portosystemic gradient.

-

Hyperplasia within transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) several months after placement.

-

Balloon angioplasty used to treat hyperplasia.

-

Final appearance of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) after balloon dilation.