Practice Essentials

The intravascular administration of thrombolytic agents originated in the 1960s with the intravenous (IV) treatment of pulmonary embolism. Thrombolysis by means of selective catheter infusion for vascular occlusion entered the mainstream during the 1970s. Since then, techniques for thrombolysis have branched in several directions with the treatment of thrombus and/or thrombosis in the coronary arteries, peripheral vascular and visceral arteries, dialysis grafts, veins, and IV catheters. A number of pharmacologic regimens have been used for thrombolysis (eg, urokinase, streptokinase, alteplase, reteplase, anistreplase). Each agent mediates thrombolysis by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which then degrades fibrin and fibrinogen to their fragmentary by-products. Thrombolytic agents have been used alone or with anticoagulants (eg, heparin), platelet-receptor antagonists (eg, abciximab), and plasminogen or thrombin inhibitors (eg, argatroban). [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 3, 12, 13, 14]

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) has provided guidelines for the administration of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) following acute ischemic stroke, [15] expanding the treatment window from 3 hours to 4.5 hours after symptom onset. Time is still of the utmost importance when treating stroke. [16]

Saver et al reported that treatment with tPA in the 3- to 4.5-hour window confers benefit on approximately half as many patients as treatment in under 3 hours, with no increase in harm. According to the authors, about 1 in 6 patients has a better outcome and 1 in 35 has a worse outcome. [17, 18]

According to Baekgaard et al, the use of catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) in acute iliofemoral venous thrombosis (IFVT) achieved good patency and vein function after 6 years of follow-up in a highly selected group of patients (first episode of IFVT, age < 60 yr; age of thrombus < 14 days; and open distal popliteal vein). In this study, 82% of affected limbs had patent veins with competent valves and without any skin changes or venous claudication. The authors noted that venous patency without reflux is an early indicator of clinical outcome. [19]

(See the peripheral thrombolysis imaging examples displayed below.)

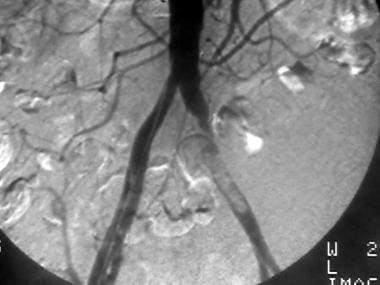

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 1. Thrombolysis of an iliac thrombus with distal occlusions. Pretreatment angiogram shows an intraluminal nonocclusive thrombus of the left common iliac artery. A Motarjeme catheter was placed just proximal to the lesion, and urokinase was infused at a rate of 60,000 U/h.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 1. Thrombolysis of an iliac thrombus with distal occlusions. Pretreatment angiogram shows an intraluminal nonocclusive thrombus of the left common iliac artery. A Motarjeme catheter was placed just proximal to the lesion, and urokinase was infused at a rate of 60,000 U/h.

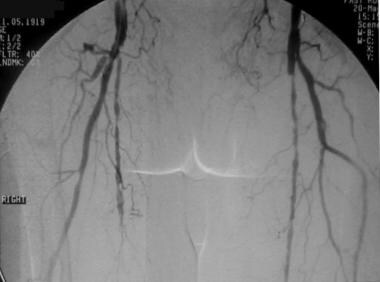

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 2. Low-dose urokinase infusion to manage femoral-popliteal occlusion. The patient had undergone left femoral-popliteal bypass grafting. Pretreatment anteroposterior (AP) pelvic image shows severe atherosclerotic disease with attenuated flow through the left superficial femoral artery (SFA), which suggests a distal occlusion. The bypass graft is not seen.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 2. Low-dose urokinase infusion to manage femoral-popliteal occlusion. The patient had undergone left femoral-popliteal bypass grafting. Pretreatment anteroposterior (AP) pelvic image shows severe atherosclerotic disease with attenuated flow through the left superficial femoral artery (SFA), which suggests a distal occlusion. The bypass graft is not seen.

Peripheral bypass thrombolysis, case 3. The patient underwent right femoral-anterior tibial bypass with ischemic symptoms in the right lower extremity. Oblique pelvic image shows complex postsurgical anatomy with a graft ostium at the proximal superficial femoral artery (SFA). A high-grade left external iliac artery stenosis is incidentally noted.

Peripheral bypass thrombolysis, case 3. The patient underwent right femoral-anterior tibial bypass with ischemic symptoms in the right lower extremity. Oblique pelvic image shows complex postsurgical anatomy with a graft ostium at the proximal superficial femoral artery (SFA). A high-grade left external iliac artery stenosis is incidentally noted.

Peripheral bypass thrombolysis, case 4. Thrombolysis of an occluded left femoral below-the-knee popliteal bypass by using the McNamara technique. Pretreatment anteroposterior (AP) image shows underlying atherosclerosis, as well as the postsurgical anatomy on the contralateral right side. The column of contrast material terminates at the left common femoral artery without an extensive collateral bed; this finding indicates an acute component to the patient's presentation.

Peripheral bypass thrombolysis, case 4. Thrombolysis of an occluded left femoral below-the-knee popliteal bypass by using the McNamara technique. Pretreatment anteroposterior (AP) image shows underlying atherosclerosis, as well as the postsurgical anatomy on the contralateral right side. The column of contrast material terminates at the left common femoral artery without an extensive collateral bed; this finding indicates an acute component to the patient's presentation.

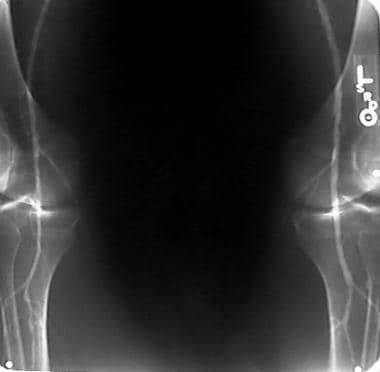

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Anteroposterior (AP) view of knees shows relatively disease-free distal run-off.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Anteroposterior (AP) view of knees shows relatively disease-free distal run-off.

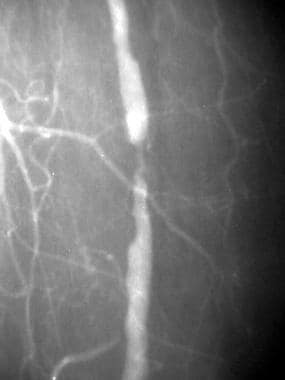

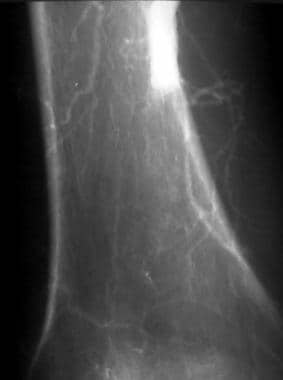

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 2. One-year follow-up angiogram demonstrates a flow-limiting stenosis, which is consistent with progression of disease in the same location as the residual stenosis demonstrated on the final postthrombolytic image obtained a year ago. The reason for the relatively rapid progression of disease is unclear. Note the relative hypertrophy of the profunda femoris branches feeding the calf.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 2. One-year follow-up angiogram demonstrates a flow-limiting stenosis, which is consistent with progression of disease in the same location as the residual stenosis demonstrated on the final postthrombolytic image obtained a year ago. The reason for the relatively rapid progression of disease is unclear. Note the relative hypertrophy of the profunda femoris branches feeding the calf.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 6. Thrombolysis of an acute thrombolytic occlusion in the popliteal artery. The patient had severe cardiac dysfunction and atrial fibrillation and presented with acute ischemia in the right lower limb 24 h after receiving an inferior vena cava filter. A hypercoagulable state was strongly suggested. Anteroposterior (AP) angiogram of the knee shows acute occlusion in the middle of the popliteal artery above the knee. Note the meniscus of the acute thromboembolus, which raises the possibility of a cardiac source. A paucity of collateral flow is noted, and distal reconstitution is poor. These findings are typical of an acute thromboembolic occlusion.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 6. Thrombolysis of an acute thrombolytic occlusion in the popliteal artery. The patient had severe cardiac dysfunction and atrial fibrillation and presented with acute ischemia in the right lower limb 24 h after receiving an inferior vena cava filter. A hypercoagulable state was strongly suggested. Anteroposterior (AP) angiogram of the knee shows acute occlusion in the middle of the popliteal artery above the knee. Note the meniscus of the acute thromboembolus, which raises the possibility of a cardiac source. A paucity of collateral flow is noted, and distal reconstitution is poor. These findings are typical of an acute thromboembolic occlusion.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 7. Thrombolysis of acute thromboembolic occlusion of the popliteal artery. Patient with severe cardiac dysfunction (ejection fraction, < 30%) with acute symptoms of right lower-extremity ischemia. Because the patient was a poor surgical candidate, the only surgical option available was above-the-knee amputation (AKA). Close-up angiogram of the adductor canal region shows an abrupt cut-off of the above-the-knee popliteal artery and poor collateral flow consistent with acute occlusion. Distal images (not shown) demonstrated poor reconstitution. A Mewissen multiple–side-hole catheter was placed across the occlusion, and low-dose thrombolysis with urokinase was begun at a rate of 60,000 U/h.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 7. Thrombolysis of acute thromboembolic occlusion of the popliteal artery. Patient with severe cardiac dysfunction (ejection fraction, < 30%) with acute symptoms of right lower-extremity ischemia. Because the patient was a poor surgical candidate, the only surgical option available was above-the-knee amputation (AKA). Close-up angiogram of the adductor canal region shows an abrupt cut-off of the above-the-knee popliteal artery and poor collateral flow consistent with acute occlusion. Distal images (not shown) demonstrated poor reconstitution. A Mewissen multiple–side-hole catheter was placed across the occlusion, and low-dose thrombolysis with urokinase was begun at a rate of 60,000 U/h.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 8. Thrombolysis of an occluded saccular popliteal artery aneurysm. Diagnostic angiogram of the right leg shows an occlusion at the adductor canal with curvilinear contrast enhancement consistent with a small thrombosed aneurysm of the popliteal artery.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 8. Thrombolysis of an occluded saccular popliteal artery aneurysm. Diagnostic angiogram of the right leg shows an occlusion at the adductor canal with curvilinear contrast enhancement consistent with a small thrombosed aneurysm of the popliteal artery.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 9. Thrombolysoangioplasty of right common iliac artery occlusion. Oblique angiogram of the pelvis shows the smooth taper of a chronic occlusion of the right common iliac artery.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 9. Thrombolysoangioplasty of right common iliac artery occlusion. Oblique angiogram of the pelvis shows the smooth taper of a chronic occlusion of the right common iliac artery.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 10. Thrombolysoangioplasty with stent placement in the occlusion in the right common iliac artery. Oblique angiogram of the pelvis demonstrates occlusion of the right common iliac artery and a proximal stenosis of the left common iliac artery.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 10. Thrombolysoangioplasty with stent placement in the occlusion in the right common iliac artery. Oblique angiogram of the pelvis demonstrates occlusion of the right common iliac artery and a proximal stenosis of the left common iliac artery.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 11. Thrombolysoangioplasty of a left common iliac occlusion. The patent distal bypass does not need treatment. Early oblique angiogram of the pelvis shows chronic occlusion of the left external iliac artery with compensatory hypertrophy of the internal iliac system.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 11. Thrombolysoangioplasty of a left common iliac occlusion. The patent distal bypass does not need treatment. Early oblique angiogram of the pelvis shows chronic occlusion of the left external iliac artery with compensatory hypertrophy of the internal iliac system.

Choice of Agent and Mechanism of Action

A number of pharmacologic regimens have been used for thrombolysis. Each agent mediates thrombolysis by converting plasminogen to plasmin, which then degrades fibrin and fibrinogen to their fragmentary by-products. Thrombolytic agents have been used alone or with anticoagulants (eg, heparin), platelet-receptor antagonists (eg, abciximab), and plasminogen or thrombin inhibitors (eg, argatroban). No thrombolytic agent or regimen has been clinically proven to be the most effective, though techniques are well published and accepted.

The original mainstay agents for peripheral thrombolysis were streptokinase and urokinase. After 1999, tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) became the de facto agent of choice. In 1998, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put on hold shipments of Abbokinase, the form of urokinase that was commercially available and in the United States. On January 25, 1999, the FDA issued an Important Drug Warning letter in which it recommended that "Abbokinase be reserved for only those situations where a clinician has considered the [therapeutic] alternatives and determined that Abbokinase is critical to the care of a specific patient in a specific situation."

In the ensuing years, other agents were substituted for urokinase for peripheral thrombolysis. American experience was greatest with tPA, which became the de facto substitute agent of choice. In popular dosing regimens, tPA was substantially cheaper to use than urokinase. Reteplase was also used less than tPA. In general, tPA is equally efficacious to urokinase except for the treatment of chronic arterial occlusive disease. Published data are limited regarding this subset of peripheral thrombolysis.The author's personal clinical experience is that complete lysis ("clean angiogram") is less often achieved with t-PA than with his prior experience with urokinase.

Urokinase

Urokinase is mentioned here for mostly historic reasons. It was briefly removed from the market due to FDA concerns during the ascendency of tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). It has not returned to common use because of a significant price differential to t-PA. Urokinase was the first commonly used interventional radiology thrombolytic agent and was typically used concurrently with IV heparin in the low therapeutic range. The cleaner end-results achievable with urokinase allowed a lower distal embolization rate. Treatment could be performed without distal protection or thrombectomy devices. Catheter puncture site hematomas were common, but major, life-threatening complications were rare. The development of catheter site bleeding was often a sign of complete lysis of the target lesion.

Urokinase is a 2-chain serine protease that contains 411 amino acid residues. Urokinase is extracted from human urine or long-term cultures of neonatal kidney cells. It has a half-life of 15 minutes and is primarily metabolized in the liver. Like streptokinase, urokinase lacks fibrin specificity and induces a systemic lytic state. Urokinase is typically given with full heparinization (activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT] 1.5-2 times control values). Titration of the dose of heparin dose is often difficult to achieve.

(See the images below.)

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 21, part 2. Because of the severity of the patient's acute ischemia, an initial course of pulse-spray thrombolysis is administered within the femoral-popliteal graft. Minimal change is noted after the administration of 250,000 U.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 21, part 2. Because of the severity of the patient's acute ischemia, an initial course of pulse-spray thrombolysis is administered within the femoral-popliteal graft. Minimal change is noted after the administration of 250,000 U.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 21, part 2. After the initial pulse-spray course of urokinase, the patient's vascular result was deemed stable enough for a low-dose infusion. Coaxial infusion in the femoral-popliteal bypass was begun with the proximal infusion port just above the origin of the graft. The infusion wire was placed in the midportion of the graft based on the fluoroscopic evaluation of flow of contrast material through the wire.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 21, part 2. After the initial pulse-spray course of urokinase, the patient's vascular result was deemed stable enough for a low-dose infusion. Coaxial infusion in the femoral-popliteal bypass was begun with the proximal infusion port just above the origin of the graft. The infusion wire was placed in the midportion of the graft based on the fluoroscopic evaluation of flow of contrast material through the wire.

Urokinase may be delivered as a continuous infusion through a single port or multiple ports (McNamara technique) or as a pulse-spray (Bookstein technique). Dosing as a continuous infusion has traditionally be divided into low-dose (60,000 U/hr), medium-dose (120,000 U/hr), and high-dose (240,000 U/hr) regimens. The choice of regimen depends on the degree of ischemia, the interval to the next angiographic evaluation, and the physician's preference. Urokinase is reconstituted with sterile, nonbacteriostatic water and then placed in an IV bag of normal sodium chloride solution. The concentration is adjusted for an infusion rate of at least 30 mL/hr per port and no more than 120 mL/h total. [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

The coauthor recommends an infusion of 240,000 IU/hr for 2 hours or until antegrade flow is restored. This dosage is reduced to 120,000 IU/h for another 2 hours and then 60,000 IU/hr until lysis is complete.

The first author's experience is predominantly with acute-on-chronic severe and limb-threatening ischemia, which is an outlier group in most published data. Infusions of 60,000-100,000 U/hr for as long as 72 hr had the greatest patency rate and the lowest major bleeding rate. Success (complete or near-complete lysis) of approximately 90% was achieved (unpublished observations; Veterans Affairs [VA] West Side, Chicago, Ill, 1991-2002). Rates of nonsurgical catheter-site bleeding were 20-30%. Transfusions were required in 5%. Periprocedural mortality was less than 1%. The development of increasing catheter-site bleeding (typically in the middle of the night) heralded complete lysis, and urokinase was discontinued until confirmatory angiography the next morning. The first author's anecdotal experience with chronic occlusive disease showed that urokinase was associated with a lowered rate of clinical failure due to nonlysis.

Streptokinase

Early thrombolysis efforts were with streptokinase, which is obtained from group c beta-hemolytic Streptococcus bacillus. It has no intrinsic enzymatic activity. After patients receive streptokinase, their antibody titers to the agent transiently increase. The antibodies irreversibly inactivate the streptokinase in a 1:1 ratio. All antibody sites must be saturated before streptokinase can be effective. Should the patient receive streptokinase again before the titers returned to baseline, the residual circulating antibodies neutralize some of the dose administered and reduce the bioeffectiveness of the agent. These inactivating antibodies result from previous streptococcal infections.

After the antibodies are depleted, the half-life of streptokinase is about 80 minutes. Levels of antibodies vary among individuals. Alpha2-antiplasmin does not inhibit the streptokinase-plasminogen complex.

Uncertainty in appropriate dosing has contributed to the unpopularity of streptokinase in clinical practice despite its substantial cost advantage over other lytic agents. Results also suggest that bleeding complications might be higher with streptokinase than with urokinase or tPA. Despite these relative disadvantages, streptokinase remains a feasible thrombolytic agent.

Although allergic reactions are rare, the main difficulty with streptokinase is related to its antigenicity. Adverse reactions include allergic reactions, rare instances of anaphylaxis, and fever. Streptokinase is supplied as in vials containing 250,000, 750,000, or 1,500,000 IU of the protein.

Recombinant human tissue-type plasminogen activator

Alteplase is a serine protease that is produced by recombinant DNA technology and that is chemically identical to human endogenous tPA. It acts by stimulating fibrinolysis of blood thrombi. Alteplase promotes the binding of plasminogen to the fibrin thrombus in conjunction with the increased affinity of fibrin-bound tPA for plasminogen, and it facilitates the ordered adsorption of plasminogen and its activator to the fibrin surface. Of special importance is the fact that alteplase appears to have a shorter half-life (about 5 min) and a higher fibrin specificity than those of urokinase in vitro.

The clinical differences between tPA and urokinase are incompletely understood. Extensive clinical experience and trials have established the safety and efficacy of alteplase in the treatment of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, and acute ischemic cerebral infarction. This agent is emerging as the thrombolytic of primary consideration in the setting of peripheral arterial occlusion. Alteplase is now firmly established as the thrombolytic treatment of choice for the management of acute myocardial infarction. It is also indicated for the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism and acute ischemic stroke.

Several tPA products are available. A double-chain formulation is produced under roller-bottle (rb) culture conditions, whereas alteplase refers to primarily the single-chain, suspension-culture product. For clinical trials conducted outside North America, the single-chain suspension culture product is referred to as alteplase.

Recombinant tPA (r-tPA) has been the agent most frequently used in peripheral arterial occlusion. Early data with tPA dosing suggested by cardiology data with concomitant heparin indicated troubling rates of intracranial bleeding complications in patients treated with doses of tPA higher than those currently used. Current regimens use 0.25-1.00 mg tPA/hr with subtherapeutic heparin dosing of 300-500 U/hr. Clinical results similar to those of urokinase with no increased rate of intracranial hemorrhage are reported.

The author uses tPA at a rate of 0.48 mg/hr for low-dose infusion protocols (4 mg tPA/500 mL normal saline at 60 mL/hr) and 0.96 mg/hr for high-dose infusion protocols (4 mg rtPA/250 mL normal saline at 60 mL/hr). IV heparin is given at 400 U/hr. The aPTT is not followed during the course of treatment. Incomplete lysis or lysis stagnation (no improvement over a 12-24 hour period) is more common in the author's experience.

A bolus of 4-8 mg t-PA may be given within the thrombus to "lace" the lesion at the beginning of therapy. The author has found the bolus technique to be safe in hundreds of similar dialysis shunt access declotting procedures. Bolus t-PA administration should not be confused with high dose tj-PA infusion, which has been associated with a high rate of intracranial bleeding and other complications.

Other thrombolytic agents

Reteplase has been used in peripheral vascular occlusion with favorable results. It is a nonglycosylated mutant of human tPA lacking the finger-epidermal growth factor and Kringle 1 regions. Reteplase is somewhat attractive as a suitable replacement for urokinase. The agent has a half-life similar to that of urokinase (13 vs 14 min, respectively). Like urokinase, reteplase lacks the fibrin affinity of r-tPA, a property theoretically linked to an increased risk of distant hemorrhagic complications. Dosing of 0.2-0.5 U/hr has been shown to be effective. Concomitant abciximab 0.25 mg/kg given as a bolus and as an infusion of 0.125 mcg/kg/min substantially reduces embolic events.

Anistreplase is an equimolar complex of streptokinase and para-anisoylated human Lys-plasminogen, or anisoylated plasminogen-streptokinase complex (APSAC), in which the active site in the plasminogen moiety is reversibly blocked by acylation. Anistreplase is not being used for peripheral vascular work. Several other new thrombolytic agents are under review, but only recombinant human urokinase, recombinant glycosylated pro-urokinase, and recombinant staphylokinase have been used for peripheral arterial occlusion. Early data suggest that recombinant glycosylated pro-urokinase and recombinant staphylokinase may be effective without inducing fibrinogen depletion. This fibrinogen-conserving property may prove to be a tremendous advantage in lessening hemorrhagic complications from thrombolytic therapy.

Streptokinase and APSAC are not generally used in peripheral vascular occlusion. In vivo studies have shown that ultrasound augments fibrinolysis and plasminogen activator, but further studies are needed before ultrasound can be introduced into clinical practice. [26, 27, 28, 29, 30]

Acute and Chronic Ischemia

Peripheral vascular ischemia results from a combination of atherosclerotic stenosis and thrombosis. In situ thrombosis occurs in a region of low flow due to a critical stenosis. Thromboemboli or atheroemboli may also lodge in stenoses or bifurcations, causing occlusion. Thrombosis propagates in the now-stagnant blood until it reaches an area where collateral blood flow is rapid enough to inhibit further thrombosis. Local flow dynamics eventually mold the occlusion into the typical chronic occlusion appearance.

This process is generally a slow one that allows the body to partially compensate by developing collateral circulation. Depending on the severity and comorbid factors, progressive arterial insufficiency may cause claudication (exertional pain), rest pain, or necrosis or gangrene. Treatment may begin electively unless the patient presents with an acute ischemia component that threatens limb loss.

The paradigm for acute limb-threatening ischemia (ALLI) is a patient presenting with an acute thromboembolic occlusion. This may occur in the absence of clinically significant preexisting atherosclerotic stenoses. Thrombi may originate from the heart, a proximal aortic aneurysm, or a hypercoagulable state. The patient presents with ALLI because the body has had inadequate time to develop adequate collateral circulation. Severe acute ischemia requires urgent treatment. In its purest and most severe form, acute arterial occlusion should be remedied within 4-6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

A patient with preexisting disease often has an acute setback and presents with a combination of acute and chronic ischemia.

The clinical boundary between threatened and irreversible ischemia is somewhat subjective and may be affected by differences in treatment philosophy and clinical experience. Familiarity with the clinical language used in the treatment of lower-extremity ischemia can help bridge the gaps of perception and clinical approach.

The Fontaine classification (see below) is the classic scheme used to describe chronic peripheral vascular ischemia.

Table 1. Original Fontaine Classification Scheme for Chronic Ischemia (Open Table in a new window)

Stage |

Symptoms |

I |

Asymptomatic |

II |

Intermittent claudication |

II-a |

Pain-free, claudication with walking >200 m |

II-b |

Pain-free, claudication with walking < 200 m |

III |

Rest and/or nocturnal pain |

IV |

Necrosis and/or gangrene |

Table 2. Updated Fontaine Classification Scheme for Chronic Ischemia (Open Table in a new window)

Grade |

Grade and Category |

Clinical Details |

0 |

0 |

Asymptomatic |

I |

1 |

Mild claudication; patient can complete treadmill exercise. |

2 |

Moderate claudication |

|

3 |

Severe claudication; patient cannot complete treadmill exercise. |

|

II |

4 |

Ischemic rest pain |

5 |

Minor tissue loss; patient has a nonhealing ulcer and/or focal gangrene |

|

III |

6 |

Major tissue loss; patient has a functional foot that is no longer salvageable |

From a treatment perspective, disease stages III and IV or grades II and III may be considered to involve chronic threatened limb loss.

Acute limb ischemia may be categorized as viable, threatened, or irreversible [31] , as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Classification of Acute Limb Ischemia (Open Table in a new window)

Description |

Category |

||

Viable |

Threatened |

Irreversible |

|

Clinical description |

Not immediately threatened |

Salvageable if promptly treated |

Major tissue loss, amputation unavoidable |

Capillary return |

Intact |

Intact, slow |

Absent (marbling) |

Muscle weakness |

None |

Mild, partial |

Profound, paralysis (rigor) |

Sensory loss |

None |

Mild, incomplete |

Profound anesthetic |

Arteriovenous Doppler finding |

Audible |

Inaudible or audible |

Inaudible |

Elevation pallor may be graded on a scale of 1-4. The return of color and the venous filling time may be classified as normal, moderate ischemia, and severe ischemia.

In the author's experience, irreversible ischemia may be successfully treated if intervention is begun in a timely fashion. The paradigm is a patient with subacute thrombosis of a distal femoral–below-the-knee venous bypass. As time passes, the thrombosis progresses down the tibial vessels, eventually causing profound ALLI and pain. Successful treatment is expected to take several days, with a nontrivial incidence of bleeding. The patient must be monitored for improvement or deterioration of vascular status, signs of sepsis, bleeding, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Close collaboration with vascular surgical and ICU teams is a must. A variation on this presentation is the patient with an additional thrombosis of an aorto-bifemoral bypass graft.

Clinical improvement after treatment may be graded as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Classification of Clinical Improvement (Open Table in a new window)

Grade |

Clinical Description |

+3 |

Markedly improved; symptoms absent or markedly improved; ABI* >0.90 |

+2 |

Moderately improved; still symptomatic but improvement of at least 1 category; ABI increase >0.10 |

+1 |

Minimally improved; ABI increase >0.10 but no categorical improvement, or vice versa |

0 |

No change in category or ABI change < 0.10 |

-1 |

Mildly worse; no category change or ABI change < 0.10 |

-2 |

Moderately worse; 1 category worse or unexpected minor amputation |

-3 |

Markedly worse; more than 1 category worse or unexpected major amputation |

*ABI indicates ankle-brachial pressure index. |

|

Indications and Contraindications

Catheter-mediated thrombolysis is useful in the treatment of both acute and chronic vascular occlusion and thromboembolus, and it is an option for native bypass graft occlusions. Thrombolysis is a reasonable option for patients with acute lower-limb ischemia for the prevention of amputation, with a mortality rate comparable to that of surgical interventions, with improved outcomes.

Among the potential advantages of catheter-directed thrombolysis are avoidance of endothelial injury because of lack of mechanical trauma, dissolution of thrombus even in the distal territory of the occlusion, and reduced risk of rethrombosis. With resolution of thrombus, catheter-directed thrombolysis may uncover the underlying atherosclerotic stenosis and, therefore, may aid in selection for subsequent appropriate interventional treatment modalities. [32] The main concern of catheter-directed thrombolysis is bleeding complications. One study found that lower doses of fibrinolytics lead to similar success rates at a cost of longer treatment duration but with less bleeding. [33]

Chronicity alone is not a contraindication for thrombolysis. Results in individual patients vary substantially, and offering a trial of thrombolysis to patients with salvageable limbs regardless of the age of the occlusion is reasonable. Most angiographers have anecdotal experience with the incidental lysis of a long-standing native arterial occlusion in the treatment of a bypass graft occlusion.

More germane than chronicity is the degree and severity of ischemia and whether an acute limb-threatening situation is present. The limb threat that chronic ischemia causes is typically less time sensitive than the threat due to acute ischemia. Patients with chronic ischemia often present with chronic rest pain or tissue loss. The relative stability of the situation allows the treatment team the opportunity to treat the patient on a relatively elective basis, both in terms of the length of treatment and when to start therapy. When the patient's condition allows it, thrombolytic therapy can be scheduled for a Monday morning. This scheduling minimizes issues about the availability of clinical support during the course of treatment and should reduce complications.

In contrast, ALLI is a vascular surgical emergency. The classic constellation of signs and symptoms are the 5 P s: pain, pallor, pulselessness, paralysis, and paresthesia. In the traditional surgical doctrine, the acutely ischemic limb can be successfully revascularized within 4-6 hours after the start of symptoms. The feared complication of delayed revascularization is reperfusion syndrome.

Reperfusion syndrome occurs when prolonged and severe ischemia occurs. Reperfusion syndrome, which follows extremity ischemia, has 2 components: (1) a local response, which consists of limb swelling with its potential for aggravating tissue injury, and (2) a systemic response resulting in multiorgan failure and death. Skeletal muscle tissue appears to be most vulnerable to ischemia.

Pathophysiologic studies reveal that irreversible damage to muscle tissue starts after 3 hours of ischemia and is nearly complete at 6 hours. Progressive microvascular damage appears to follow rather than precede skeletal muscle tissue damage. The more severe the cellular damage, the greater the microvascular changes. With the death of tissue, microvascular flow ceases within a few hours; this is the no-reflow phenomenon. Compartment syndrome occurs at this point, and further tissue swelling ceases.

The inflammatory responses after reperfusion vary greatly. Thrombotic or embolic limb occlusion is the most common cause of reperfusion syndrome, in which a variable degree of ischemic damage occurs in the zone where collateral blood flow is possible. The extent of this region determines the magnitude of the inflammatory response, whether local or systemic. Only in this region is therapy of any benefit. Treatments may include fasciotomy to prevent pressure occlusion of the microcirculation or anticoagulation to prevent further microvascular thrombosis. Because the process of clotting generates many of the inflammatory mediators, anticoagulation has additional benefit of decreasing the inflammatory response. When most of the lower extremity is involved, amputation rather than attempts at revascularization may be the most prudent course to prevent the toxic product in the ischemic limb from entering the systemic circulation. [34]

Adult respiratory distress syndrome, shock, DIC, and renal failure are common systemic sequelae. The mortality rate associated with reperfusion syndrome is high.

Catheter-mediated thrombolysis has allowed modification of the traditional doctrine. The gradual way in which thrombolysis reestablishes flow allows the toxic metabolites to be mobilized over time and allows the patient to tolerate the systemic effects more easily than before. Patients with small-vessel occlusion are poor candidates for surgery because of the absence of a good distal bypass target. These patients should especially be offered a trial of thrombolysis. Exceptions to this approach are situations involving contraindications to thrombolysis or other emergency comorbidities or ischemia so severe that the treatment time is of paramount importance.

Candidates for thrombolysis are rarely in an ideal clinical condition. The major contraindications of thrombolysis are recent stroke or malignancy, particularly with the possibility for brain metastases. Renal insufficiency, allergy to contrast material, cardiac thrombus, diabetic retinopathy, coagulopathy, and recent arterial puncture or surgery are relative contraindications. The presence of a suitable arterial access site and the patient's ability to tolerate the treatment and cooperate during the procedure must be considered. Thrombolysis is rarely a treatment-versus-nontreatment decision. Rather, a range of surgical and nonsurgical strategies may be considered in treating the difficult case. [5]

Thrombolysis Technique

Treatment paradigm

Lower-extremity arterial occlusion typically occurs as part of broad processes involving in situ thrombosis and/or embolization, for which the author uses the term thromboembolic occlusion. In situ thrombosis occurs when a local flow disturbance acts as a nidus to initiate the coagulation cascade. The flow disturbance can be due to local thrombosis or proximal embolus (typically thrombus.) Local thrombosis may be caused by a flow disturbance due to an underlying flow-limiting lesion, either a stenosis or an extrinsic or positional compression.

Hypercoagulable states, congenital or acquired (eg, dehydration), may also promote the formation of thrombus. Coagulation disorders should be considered in all patients presenting with early bypass failure, for whom the incidence is higher than that of the general population.

Once begun, thrombosis propagates both proximally and distally to the nidus until blood flow from an adjacent vessel is sufficient to prevent further propagation. Most bypass grafts have no internal branching, and occlusion extends the length of the graft. The thrombus may eventually continue into the native arterial system. The contour of the leading edge of the thrombus evolves in response to the local flow pattern, becoming smooth and physiologic in appearance with time.

Patient assessment and treatment

The treatment paradigm is based on the following factors:

-

The lesion underlying an arterial occlusion is often smaller than the overall thrombosis

-

Short lesions are more likely than long ones to have a good clinical outcome

-

If a long-segment occlusion can be converted to a short one, the success rate and longevity (patency) of the intervention improves

A patient with an occlusion is given a trial of thrombolysis. If successful, this treatment shortens or at least softens the occlusion. After the thrombus resolves, the shortened lesion may be treated with conventional surgical or percutaneous techniques based on the new size and configuration of the lesion. Technical success and patency results are then based on the postthrombolytic appearance of the smaller lesion. [4]

This paradigm has been called thrombolysoangioplasty (TLA). Bypass occlusions typically have a relatively short segment, high-grade stenosis at the distal anastomosis, which may be addressed with surgery or angioplasty. A focal stenosis, such as one in the adductor canal region, may cause occlusions in the superficial femoral artery (SFA). The SFA and popliteal arteries have relatively few collateral connections and therefore allow a thrombosis to extend for some distance. The angiographic appearance may yield few clues about the underlying disease. Because atherosclerosis tends to be bilaterally symmetrical, the contralateral diagnostic angiogram may offer clues to the merits of attempting TLA.

Thrombolysis may be considered after initial consultation and patient evaluation. The patient must be in medically stable condition with adequate renal and coagulation function and an ability to cooperate and safely tolerate the therapy. Written informed consent must be obtained with an explanation of the disease process, proposed treatment indication, technique, risks, and alternatives.

If clinically significant pain, dementia, delirium, or psychiatric illness is present, an anesthesiologist may be consulted. Use of intravenous sedatives and/or analgesics or a nerve block may be considered. General anesthesia may be considered for uncooperative patients with limb-threatening ischemia and a high surgical risk. Because of the risk of bleeding, spinal anesthesia should be avoided. Likewise, any measures that reduce a patient's level of consciousness should be used with caution, because a change in mental status is an early sign of intracranial hemorrhage.

The lytic agent may be delivered by using a slow infusion through 1 or more sites or ports (McNamara technique) or by using a pharmacomechanical pulse-spray technique (Bookstein method). Pulse-spray thrombolysis can have a speed advantage compared with slow infusion techniques, but it is labor intensive, and it may be associated with a higher rate of distal arterial embolization. The author reserves the pulse-spray infusion for cases of severe acute limb-threatening ischemia or iatrogenic thromboembolus.

(See the images below.)

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 12. Late image shows reconstitution of the right common iliac artery at the level of the deep circumflex iliac branch. Low-dose urokinase infusion was begun by using the McNamara technique.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 12. Late image shows reconstitution of the right common iliac artery at the level of the deep circumflex iliac branch. Low-dose urokinase infusion was begun by using the McNamara technique.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 12. Contralateral oblique image shows that the stenosis in the proximal right external iliac artery is smooth and circumferential. The distal lesion is not seen in its ideal profile. Low-dose urokinase infusion is continued by using the McNamara technique.

Peripheral thrombolysis, case 12. Contralateral oblique image shows that the stenosis in the proximal right external iliac artery is smooth and circumferential. The distal lesion is not seen in its ideal profile. Low-dose urokinase infusion is continued by using the McNamara technique.

In McNamara's original paradigm, an end-hole catheter is placed in or near the proximal portion of the thrombus. Urokinase is infused at a rate of either 1000 U/min (low dose) or 4000 U/min (high dose). Follow-up angiography is performed after each 500,000 U administered at 8 hours for low doses and 2 hours for high doses. [35, 22, 23, 24]

Between interventions, the patient should be monitored in a setting in which experienced nursing staff can closely observe the patient. Although not required, a surgical intensive care setting is recommended. For a 60-mL/hr infusion rate, 500,000 U of UK are placed in 500 mL of normal saline for low doses and in 125 mL of normal saline for high doses.

The author prefers to use an intra-arterial infusion at a rate of no less than 30 mL/hr to maintain catheter patency. [36] Heparin is intravenously infused for an aPTT of 1.5-2 times that of the control value. The platelet count should be monitored for antiheparin antibodies in all patients receiving heparin. The use of hematologic testing during thrombolysis is controversial.

Some interventionalists advocate the use of tests to monitor the presence of a fibrinolytic state and to predict clinical outcome and occurrence of complications. However, in common clinical practice, hematologic testing is unnecessary. The result of a single coagulation procedure has no direct clinical association with outcomes of fibrinolytic testing and reperfusion, reocclusion, or hemorrhage. This is borne out by the fact that low fibrinogen level marks an increased hemorrhage risk but does not accurately predict hemorrhage in a particular patient moreover hemorrhagic complications can occur with normal levels of fibrinogen. Useful tests include daily hemoglobin or hematocrit determinations to detect occult bleeding.

Equipment required for the pulse-spray technique includes a special catheter, a Touhy-Borst–type side-port adapter, guidewire, a stopcock, and a 1-mL syringe (see the images below). The catheter has multiple, tiny side holes through which the thrombolytic agent may be directly administered within the thrombus at a high rate. The catheter is placed within the thrombus. Depending on the catheter used, a guidewire may be required to occlude the end hole.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Day 1 follow-up angiogram. The guidewire was removed, and contrast agent was injected through the Mewissen catheter. The superficial femoral artery (SFA) is partially recanalized, with good distal flow. No distal emboli were noted (images not shown).

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Day 1 follow-up angiogram. The guidewire was removed, and contrast agent was injected through the Mewissen catheter. The superficial femoral artery (SFA) is partially recanalized, with good distal flow. No distal emboli were noted (images not shown).

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Because antegrade flow is restored, multiple–side-port infusion is no longer required. A Mewissen catheter is replaced with an end-hole straight catheter. The guidewire and Touhy-Borst adapter are no longer needed, so nursing care in the ICU is simplified. The treatment team elected to increase therapy to a high-dose urokinase infusion for several hours and to recheck the patient in the afternoon.

Peripheral native arterial thrombolysis, case 5, part 1. Because antegrade flow is restored, multiple–side-port infusion is no longer required. A Mewissen catheter is replaced with an end-hole straight catheter. The guidewire and Touhy-Borst adapter are no longer needed, so nursing care in the ICU is simplified. The treatment team elected to increase therapy to a high-dose urokinase infusion for several hours and to recheck the patient in the afternoon.

Initial catheterization

The choice of arterial access site is one of individual preference and patient-specific findings. The author prefers the contralateral, retrograde, femoral approach for lower-extremity occlusions extending above the knee. A diagnostic aortoiliofemoral run-off angiogram may be obtained, and the infusion systems may be placed with relative ease in most cases. Ipsilateral antegrade (downhill) puncture may be considered when the contralateral femoral pulse is poor or when in-line access to the lesion is expected to be required, such as for small-vessel catheterization or native-vessel recanalization. The antegrade approach cannot be used for aortoiliac angiography, which would require a prior study or separate puncture.

Antegrade puncture may be associated with an increased rate of bleeding complications. Suprainguinal ligament (high) arterial puncture may occur, particularly in the obese patient. High punctures are associated with clinically silent retroperitoneal bleeding, which often manifests as hypotensive shock in the early hours of the morning. Antegrade puncture is also poorly suited for treating proximal femoral graft or native arterial occlusions because the approach provides little working room in the artery for catheter, sheath, and guidewire manipulation.

A diagnostic angiogram may be obtained to delineate the arterial anatomy. The occluded vessel or bypass graft is usually identifiable as a residual pouch or nipple. Review of previous angiograms or surgical reports and consultation with the vascular surgeon may be needed to identify the target for lysis in patients with complex anatomy. The nipple is catheterized and probed with a floppy-tip guidewire. The leading edge of thrombus is often resilient and resistant to catheterization. The catheter can then be introduced into the thrombus. Beyond the thrombus, the initial firmness conventional techniques may be used. Increased care is required when a native arterial occlusion is probed because of a risk of dissection and perforation of the artery.

The initial attempt to traverse the leading edge of the thrombus is described as a guidewire traversal test. The guidewire is passed through the whole length of the thrombus before initiation of prolonged infusion with the catheter embedded in the proximal thrombus. If a guidewire cannot be passed through the thrombus, it is probably organized and less likely to clear with thrombolysis. With passage of nonhydrophilic guidewire, initial success with clot lysis is most likely with a thrombus less than 7 days old. [35, 37, 38]

Special lytic-agent infusion techniques are required only until antegrade flow is restored in the vessel. Once partial patency is restored, the agent needs to be infused only from a point proximal to the residual thrombus. The agent is then carried by the flowing blood and bathes the residual thrombus until the endpoint is reached.

Choice of technique and catheters

The choice of technique is mostly a personal one that is influenced by personal experience and based on the particular details of the individual patient and the issues related to the medical center or referring clinicians. No single dose or technique is generally accepted for performing thrombolysis. In vitro evidence suggests the choices between continuous versus pulsed infusion and between UK and sodium chloride solution involve trade-offs in speed of lysis and in the size and number of distal emboli treated. The author prefers low-dose infusion protocols in patients with noncritical ischemia. The somewhat slower rate of lysis allows more flexibility in the follow-up schedule and seems to provide more time for recognizing bleeding complications when they occur. At the author's institution, this approach is well tolerated by patients and accepted by clinicians.

Catheter infusion systems are available in different configurations and French sizes, and either general-purpose or function-specific types are available. The author prefers to use a 5F catheter placed through a 6F introducer sheath. The use of the oversized 6F introducer sheath allows the intensive care team to obtain blood samples while avoiding the risks of phlebotomy during thrombolysis.

The infusion catheter may be specifically designed for lysis, or it may have a general-purpose end hole (straight or curved) or multiple side holes. The author finds the Neff catheter to be particularly versatile in this regard. The multiple side holes allow the injection of contrast material at rates as high as 15 mL/s for diagnostic angiography. The curve and material of the catheter allow it to be used for the selective catheterization of the occluded vessel down to the midthigh area. The Neff and the similarly shaped Motarjeme catheters may be used with a 0.035-in coaxial infusion microcatheter or wire. General-purpose catheters are relatively inexpensive and can be used in situations in which direct infusion over a long proximal segment of the occlusion is not needed.

Advantages of end-hole catheters include the following:

-

End-hole catheters permit extension of the diagnostic angiogram. They are used for initially traversing the occluded segment.

-

These catheters are simple to use.

-

They are inexpensive.

-

Follow-up angiography can be readily performed.

-

Peripheral small-vessel occlusions are best managed with end-hole catheters because the occluded target vessels are usually too numerous and too small to be infused separately.

-

End-hole catheters are suitable alternatives when the anatomy is unfavorable for the use of coaxial or multihole catheters.

Disadvantages of end-hole catheters include the following:

-

These catheters are relatively unstable.

-

Continuous monitoring is needed when the catheter is advanced.

Advantages of coaxial end-hole catheters include the following:

-

These are more stable than conventional end-hole catheters. Their construction protects against inadvertent dislodgement of the infusion catheter.

-

These catheters have a smaller profile and therefore result in less pericatheter thrombosis.

-

The need to manipulate the catheter is reduced.

-

Although the evidence is not conclusive, lysis may be faster with coaxial end-hold catheters than with other catheters.

Disadvantages of coaxial end-hole catheters include the following:

-

The tip of the catheter is difficult to see on fluoroscopy.

-

The infusion guidewire is fragile.

-

Manipulation of catheter is still necessary.

-

Two infusion pumps may be required.

-

Fluids and lytic agents may not flow easily because of the small lumen.

Advantages of multi–side hole catheters include the following:

-

The catheters tend be more stable than end-hole catheters.

-

They permit wider exposure of the thrombus to the lytic agent.

-

The lytic agent is evenly dispersed.

-

The need for catheter monitoring is reduced.

-

These catheters are simple to use.

-

Their flow characteristics are better than those of coaxial systems.

Disadvantages of multi–side hole catheters include the following:

-

Multi–side hole catheters are expensive.

-

Their structure is more complex than that of other catheters.

-

Many require 2 infusion pumps when co-axial catheters are used.

-

Many require obturating wires.

-

Angiographic studies are difficult to perform through some of these catheters.

The first major modification to the McNamara technique was the development of coaxial infusion. Coaxial infusion is designed to provide uniform delivery of the agent to the thrombus while maintaining the convenience of a slow infusion. This technique is particularly helpful for treating bypass grafts. After the proximal firm thrombus is traversed, the risk of wire induced vessel damage is low. The central portion of a thrombosed graft generally contains soft thrombus that allows for easy wire and catheter manipulation.

Three devices are required for coaxial infusion: an infusion catheter, an infusion wire or microcatheter, and a Touhy-Borst–type side-port adapter.

The infusion catheter is usually a 5F catheter with multiple distal side holes for infusion with a tapered end hole to seal against the inner device. Another design may be used to limit infusion to the side holes. The catheter may be function specific, or it may be a general-purpose device.

The infusion wire or microcatheter is usually a 0.035- or 0.038-in (3F) device with either an end hole or multiple side holes. The size of the infusion wire should be matched to the size of the catheter end hole for proper function.

A Touhy-Borst–type side-port adapter is used to allow simultaneous infusion and to make a fluid-tight seal between the inner and outer catheters.

The infusion wire is placed through the infusion catheter. The outer infusion catheter is placed so that the infusion from the proximal side hole bathes the leading edge of the thrombus. The inner infusion wire is placed to infuse the distal portion of the occlusion. The ideal position of the inner wire allows for flow of the agent so that the distal thrombus plug lyses only after most of the proximal thrombus has been dissolved. This way, the risk of distal embolization is minimal. The same total lytic agent dose is used as with the original McNamara technique, divided between the ports. The division can be equal or unequal depending on the clinical circumstances. With the same concentration as above, low-dose tPA can be delivered at a rate of 30 mL/hr per port, for a total dose of 0.48 mg/hr.

Short occlusions may be treated with a multiple–side-port catheter without the infusion wire. Infusion catheters are available with infusion lengths of 20 cm or longer, and they may be used with a conventional guidewire. Coaxial and multiple–side-hole infusion devices are not required for successful thrombolysis.

Both end-hole and multiple–side-hole diagnostic catheters may be used with an adjustment of the position of the catheter tip so that a gentle test injection distributes contrast material through the proximal portion of the occlusion. This test fairly closely recreates the distribution of the lytic agent achieved with multiport infusion catheters, particularly with occluded bypass grafts. The author has not found any significant difference in clinical results or complication rates with different slow-infusion lysis techniques or with the vigor of the initial guidewire test. During this initial phase of treatment, use of the Touhy-Borst adapter and guidewire might also be avoided to simplify nursing care and to minimize human error.

The dose rate and follow-up schedule may be adjusted depending on clinical and time-management issues. The author uses an 8- to 24-hour follow-up schedule for low-dose infusion (tPA 0.48 mg/hr) and a 1- to 4-hour follow-up schedule for high-dose infusions (tPA 0.96 mg/hr). On occasion, 48 hours may pass before patient with a long-segment chronic occlusion undergoes angiography. In these patients, telephone and clinical follow-up are performed at 24 hours.

Two clinical factors are involved with determining the need for follow-up:

-

Treatment can be facilitated when the configuration of the infusion system is adjusted to the flow pattern and distribution of residual thrombus.

-

The bleeding risk increases with higher doses; with resolution of the thrombus; and, possibly, in the early hours of the morning.

Suction thrombectomy is an occasionally useful technique, particularly in treating small distal thromboemboli. It requires the placement of a nontapered catheter through the introducer sheath with the distal end at the thrombus. A large syringe is attached, and suction is applied while the catheter is removed in a smooth motion. The aspirate may be evaluated for thrombi by filtering the blood through gauze.

Adjunctive Medications During Thrombolysis

In clinical practice, thrombolytic techniques vary widely in terms of the choice of lytic agent and dose, the infusion technique, and the use of adjunctive agents. These variances depend on the patient population, the treatment setting, and the experience and preference of the practitioner and of the referring and consulting physicians. Thrombolytic agents such as reteplase and prourokinase may also be used, as may platelet receptor antagonists. Plasminogen and thrombin inhibitors promote lysis with tPA but not with urokinase.

Heparin is commonly though not universally used during thrombolysis. Its use ranges from dilute mixtures (3000 U/L) in flush solutions to full systemic anticoagulation with an aPTT at 1.5-2 times the control value. However, many believe that this regimen, while fine for urokinase, should be lowered significantly for tPA or r-tPA infusions because of increased risk of complications during these infusions in patients fully anticoagulated.

Maintaining therapeutic anticoagulation may be challenging.The aPTT often strays substantially above or below the traditional target of 1.5-2 times the control value. This issue cannot be easily explained solely on the basis of human error. A patient's coagulation homeostasis is likely in a state of flux as the therapy progresses.

The cardiology community has suggested theories of a diurnal rhythm in the balance between thrombosis and lysis. However, no scientific data specifically address the advantages or disadvantages of heparin therapy during thrombolysis. Despite this lack, current practice suggests that concomitant heparin administration may restrict pericatheter thrombosis and can be administered by a systemic route or around the catheter through a proximal sheath. Anticoagulation following the procedure is appropriate and should be continued until the underlying cause of occlusion has been resolved.

Heparin is contraindicated in the presence of antiheparin antibodies because dangerous thrombocytopenia can develop. Although not routinely ordered, an assay for the antibody is available. In all patients receiving thrombolysis and heparin, both the aPTT and the platelet counts should be monitored on a continuing basis. Once again, personal experience and input from the referring and vascular surgical teams are important considerations.

Treatment and Posttreatment Issues

Treatment endpoints

Several factors influence the speed of lysis, including the age and nature of the clot, the infusion technique, the lytic agent and dose, and the chosen treatment endpoint. Acute thrombosis generally responds faster than chronic occlusion. The literature suggests that thrombolysis can typically be performed in 18-36 hours. In the author's practice, patients often present with a picture of acute-on-chronic arterial and/or graft occlusion.

In the author's previous experience using urokinase, patients were often successfully treated with a 72- to 96-hour course of therapy, although some patients respond within 1 day. Although a 72- to 96-hour course of therapy seems to work well, it is not a standard treatment, and many interventionalists confine thrombolysis to 18-36 hours. High success rates of complete lysis (>90%) were achieved with an acceptable rate of puncture site hematoma. The author theorizes that bleeding rates might be lower by changing to subtherapeutic heparin dosing of 400u/hr.

The author's current practice is to use t-PA 1 mg/hr with IV heparin 400 U/hr for 18-36 hours. Experience has shown that if lysis is incomplete at 36 hours, additional days of tPA are usually ineffective. Residual thrombus is prone to distal embolization during any subsequent intervention, and appropriate measures must be taken. Stent/sten tgraft, thrombectomy, and distal protection are important tools in these cases.

The choice of therapeutic endpoint may be subject to discussion. The theoretical endpoints to thrombolytic therapy are the following: (1) clinical success (ie, the resolution of thrombus and symptoms); (2) treatment arrest or failure, or the failure to improve either angiographically or clinically; and (3) complications necessitating the termination of therapy (eg, major bleeding, stroke, sepsis, gangrene, pulmonary edema, heart failure, shock, or an inability to cooperate).

The patient's overall condition and the treatment alternatives, as well as the experiences of the clinicians involved, affect these seemingly clear endpoints. The degree of thrombus resolution that indicates success varies from 95% lysis to total lysis without evidence of residual thrombus.

Historically, the treatment team at the author's institution was aggressive in treating patients with severe peripheral vascula, who often have severe atherosclerosis, bypass grafts, and calf-vessel occlusion. These patients had already undergone several surgical interventions, with multiple comorbidities, including defects of coagulation. Because they were poor surgical candidates, they were offered an aggressive course of thrombolytic therapy that usually extended over several days. In the absence of major complications, treatment was continued until the thrombus completely resolved or until no evidence of clinically significant improvement was noted in 4-24 hours.

Catheter-site infection is a potentially serious complication of prolonged thrombolysis. As a precaution, all patients receiving thrombolysis for more than 72 hours are given prophylactic antibiotics. To reduce the incidence of infection, the sheath should be changed if any stents are going to be used to treat the underlying lesions, especially if the sheath has been in place for a prolonged period.

Complications

A trade-off exists between the risks of bleeding complications and the risks of thromboembolic complications. The decision is partially based on the clinical factors and the institutional tolerance for moderate bleeding complications. This trade-off also comes into play in determining the treatment endpoint. Patients in the author's practice often present with severe limb-threatening, acute-on-chronic ischemia. A significant minority of patients develop cosmetically relevant but surgically insignificant hematomas (predominantly related to the catheter site) if the target aPTT is 1.5-2 times the control value.

Slow infusion techniques are used to minimize distal embolization, which is poorly tolerated in patients with severe calf-vessel disease. The author prefers to leave a short segment of thrombus distal to the infusion device to act as a temporary barrier to embolization of the small thrombi that may break off during the lysis process. Ideally, the distal thrombus plug lyses as the proximal thrombus embolization risk abates. Transient distal embolization is a common event during thrombolysis and appears as a transient increase in rest pain or as deterioration perfusion on physical examination. These emboli resolve in a matter of hours in most patients if the lytic infusion is allowed to continue. Aggressive pain management and close clinical follow-up is recommended. Warning the patient and the nursing and surgical staff about this possibility reduces undue concern. Rarely is angiographic or surgical intervention indicated.

The overall risk of hemorrhagic stroke from a thrombolysis procedure has been reported to be 1-2.3%. About 50% of hemorrhagic complications occur during the thrombolytic procedure. Hematoma at the vascular puncture site has been reported to be 12-17%, and gastrointestinal bleeding has been variably recorded between 5-10%; hematuria following thrombolysis should provoke search for urinary tumors.

Anaphylactic reactions to streptokinase are rare, but allergic responses do occur. These are usually characterized by flushing, vasodilatation, rashes, and hypotension. The symptoms usually respond well to discontinuation of the streptokinase infusion and the administration of hydrocortisone and antihistamine. Delayed serum sickness–symptoms are a rare occurrence with streptokinase. Patients present with joint pains, fever, and microscopic hematuria 10-21 days after treatment. Most patients recover without sequelae, though irreversible renal impairment is described.

The incidence of hemorrhagic complications is decreased with alteplase compared with streptokinase, but no difference has been found in hemorrhagic complication rates between alteplase and urokinase.

Posttreatment issues

After successful thrombolysis is accomplished, the patient should be evaluated for any underlying vascular lesions that could explain the cause of the vascular occlusion. If identified, these lesions must be treated (radiologically or surgically) to prevent early recurrence of the occlusion. Patients with early bypass failure should also be evaluated for occult coagulation anomalies. Some patients may benefit from posttreatment anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy. All patients must receive close clinical follow-up. Some clinicians recommend periodic surveillance noninvasive blood-flow evaluations for the early detection of restenosis.

Clinical trials

Prospective, randomized studies performed to direct compare different thrombolytic agents are limited. The largest body of evidence supporting recombinant-based thrombolytics for this indication was derived from trials of alteplase. One open trial was performed to compare intra-arterial streptokinase to intra-arterial and IV alteplase in 60 patients with recent-onset or deteriorating limb ischemia. The initial angiographic success was significantly greater with intra-arterial r-tPA (100%) than with intra-arterial SK (80%; P< .04) or IV alteplase (45%, P< .01). The 30-day limb-salvage rates were 80%, 60%, and 45%, respectively.

Alteplase has been used extensively in the treatment of peripheral vascular occlusion. Most of the studies in this regard have been based on dose ranging. [39, 40] The largest group studied included 65 patients, with both peripheral arterial and bypass graft occlusions. [41, 42] In this study, alteplase was infused through an embedded catheter into the thrombus. Angiographically documented clot lysis was achieved in 94% of patients, whereas clinically evident thrombolysis was noted in 90% of patients, with a mean infusion time of 5.25 hours. Two failures were recorded in patients in whom the catheter could not be placed at the thrombus. Minor hematomas developed at the catheter entry site in 12.3% of patients; 4.6% developed major hematomas. After thrombolysis, 76% of patients required additional procedures, such as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or surgical revision (20 patients), and 7 patients required anticoagulation to maintain patency. One death was due to intracranial hemorrhage, which occurred 48 hours after thrombolytic therapy while the patient was receiving heparin.

In another open, randomized trial (32 patients), alteplase initially produced significantly faster lysis than urokinase, but the 24-hour and 30-day success rate was not statistically different. In the Surgery Versus Thrombolysis for Ischemia of the Lower Extremity (STILE) study, designed to evaluate surgery versus thrombolysis for lower extremity ischemia, efficacies or bleeding complications did not differ in patients receiving alteplase compared with those receiving urokinase.

A study by Krupski et al was designed to evaluate the efficacy of 2 doses of alteplase in patients with acute or subacute peripheral arterial occlusion. The patients were randomly assigned to receive 0.05 or 0.025 mg/kg/hr given through catheter positioned adjacent to the thrombus. No heparin was administered during the procedure, but all patients were given IV heparin after successful thrombolysis. The mean infusion duration was 3.1 hours among patients who received the high rate and 7.4 hours in patients treated with the low infusion rate. Secondary procedures were required in 5 of 7 patients to maintain patency. [43]

A randomized, controlled trial was performed to compare intra-arterial alteplase and urokinase in 32 patients with peripheral arterial occlusion of up to 90 days' duration. [44, 45] The endpoint of this study was clot lysis of greater than 95%, as evaluated with serial angiograms at baseline and at 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours. Alteplase was administered to 16 patients as a 10-mg bolus followed by an infusion of 5 mg/hr for up to 24 hours. Urokinase was given to 16 patients as a 60,000-IU bolus followed by an infusion of 240,000 IU/hr for 2 hours, 120,000 IU/hr for 2 hours, and 60,000 IU/hrr for up to 20 hours. All patients received concomitant heparin (3000-5000 U bolus, 600-1000 U/hr).

Eight patients treated with alteplase and 9 patients given urokinase required surgical intervention within 30 days. Three alteplase-treated patients and 5 urokinase-treated patients underwent angioplasty within 30 days. Hemorrhagic events were similar in the 2 groups. The fibrinogen level at 24 hours was significantly lower among patients who received alteplase than those who received urokinase. The authors concluded that alteplase therapy was associated with faster clot lysis; however, 30-day clinical success rates did not significantly differ. The incidence of hemorrhagic complications was greater with alteplase therapy than with urokinase, although this difference was not statistically significant. [44, 45]

A nonrandomized comparison of alteplase and urokinase was performed in 28 patients who received intra-arterial urokinase 40,000-200,000 U. [46] An additional 28 patients received alteplase 2.5-7.5 mg. The occlusions were as old as 4 months. The length of the thrombus averaged 7 cm in the alteplase group and 8 cm in the urokinase group. Primary success was achieved in 86% in the alteplase group (mean duration of treatment, 2 hr) and 75% in the urokinase group (mean duration of treatment, 6 hr). Angioplasty was required in 18% of the alteplase group and 21% of the urokinase group. Local hematoma was twice as common in the urokinase group as in the alteplase group (7% vs 14%).

Findings from another trial of alteplase or urokinase for peripheral arterial occlusion confirmed the efficacy and safety of alteplase. After diagnostic angiography, 22 patients received urokinase 4000 U/min, and 23 patients received alteplase 0.05 mg/kg/hr. Arterial patency was assessed with serial arteriography at 4, 8, and 18-24 hours. Patency was graded from 0 (no flow) to 3 (full flow, no residual thrombus). Complete thrombolysis was successful in 86% of the urokinase group and in 91% of the alteplase group. The mean infusion times for alteplase and urokinase were 4.5 and 18.7 hours, respectively, with mean doses of 27 and 4.34 million U, respectively.

Four patients in the alteplase group developed catheter-site bleeding compared with 1 patient in the urokinase group. One patient treated with urokinase had an intracranial bleed. Nausea and vomiting occurred in 14 urokinase-treated patients. Patients in whom reperfusion was not achieved with either agent were characterized by severe, uncorrectable disease that was intrinsic or immediately adjacent to the artery or bypass graft.

In another study to confirm the efficacy of alteplase, investigators evaluated 120 patients who were matched for age, sex, and disease severity (Fontaine classification) and were treated with alteplase (n = 60) or urokinase (n = 60) administered through an intra-arterial catheter. [47]

In a randomized study, thrombolysis with alteplase or urokinase was used in conjunction with heparin delivered intra-arterially and locally. [47] Heparin therapy was initiated prior to thrombolysis and continued for 5 days after therapy. Alteplase was given as a 5-mg bolus followed by a 5-mg/hr infusion, whereas urokinase was infused at 60,000 IU/hr.

Initial patency was achieved in 85% and 73% of patients in the alteplase and urokinase groups, respectively, as assessed by means of angiography. Reocclusion developed in 8 patients within 72 hours in the alteplase group and within 10 hours in the urokinase group. The duration of therapy was 1-4 hours (median, 2 hr) for alteplase and 6-72 hours (median, 24 hr) for urokinase. Catheter-site bleeding occurred in 15% and 8% of patients alteplase and urokinase, respectively. No major bleeding complications occurred during thrombolysis; however, during postlytic treatment with heparin, GI hemorrhage developed in 1 patient in the urokinase group; this responded to conservative management. At 6-month follow-up, patients treated with alteplase had rates of amputation, reocclusion, and Fontaine stage III and IV disease lower than those of patients in the urokinase group. [47]

A combination of streptokinase and heparin was compared with alteplase in a dose-ranging trial evaluating safety and efficacy in 28 patients with limb-threatening ischemia of less than 1-month duration (median, 7.5 days). Four infusion rates of alteplase were studied in 23 patients: 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 mg/hr. The median duration of infusion was 22 hours for alteplase and 38 hours for streptokinase and heparin. Clot lysis was achieved in all patients in the alteplase group; the speed of clot lysis appeared to be dose related. All patients received heparin therapy after successful thrombolysis. [48]

Hemorrhagic complications occurred in 29% of patients. Four patients (17%) had major hemorrhagic complications: Three cases occurred at the infusion rate of 2.5 mg/h, and 1 patient receiving 2.5 mg/h developed an intracerebral bleed. Fibrinogen concentrations decreased below 120 mg/dL in 22% of patients treated with alteplase and in 40% of streptokinase/heparin-treated patients; this was identified as a risk factor for bleeding. The authors concluded that an infusion of alteplase at 0.5 mg/hr was effective and had fewer complications than higher doses of alteplase. [48, 49]

Further work by the same group involved an intra-arterial dose of alteplase 0.5 mg/hr given to 13 patients with acute and subacute occlusion. Two patients required a second therapeutic course of alteplase: 1 for reocclusion 2 weeks after angioplasty of a residual stenosis; the other for rethrombosis at 4 months after initially successful thrombolysis. The mean duration of ischemia was 18 days. The mean length of the occlusion was 18 cm; 3 patients (23%) had occlusions longer than 25 cm. Six patients (46%) had no demonstrable distal runoff vessels at the time of angiography.

Patients were treated with alteplase 0.5 mg/hr for a mean of 26.2 hours. Patients received heparin for 5 days after thrombolysis or angioplasty, and warfarin therapy was started on day 3. Angiographic evidence of lysis was noted in all patients; however, this was not enough to reperfuse the distal limb in 2 patients with previously noted absence of runoff. Minor groin hematomas developed in 4 patients. (Three of these patients underwent angioplasty.) Two other patients developed reocclusion despite angioplasty. Fibrinogen levels were reduced to 66% of baseline. No major complications were reported. The limb-salvage rate at 30 days was 87%. The authors concluded that intra-arterial alteplase at 0.5 mg/hr appeared to be a safe and effective regimen for the treatment of acute peripheral arterial occlusion.

In a separate analysis, these 13 patients were compared with 15 patients who received intra-arterial alteplase 0.5 mg/hr plus intra-arterial heparin. The mean total dose of alteplase was 15 mg. Patients with emboli less than 2 days old or neurologic deficit of the involved limb were excluded. Results of combination therapy were similar to those achieved by alteplase alone. This finding prompted the authors to comment that the use of concurrent heparin did not appear to produce additional benefit. Two patients in each group developed rethrombosis. No major hemorrhagic complications occurred. Puncture-site hematomas occurred in 13% of patients.

Another group compared intra-arterial streptokinase and alteplase in 98 and 69 patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease, respectively. Patients received streptokinase (5000 U/hr) or alteplase (0.5 mg/hr in 51 patients and 0.25-2.5 mg/hr in 18 patients). Criteria for successful lysis included angiographic proof, increase in the ankle-brachial index (ABI), limb salvage at 30 days, absence of clinical evidence of rethrombosis, or no need for intervention (other than angioplasty) at the site of thrombolysis. [49]

With these criteria, successful thrombolysis was achieved in 41% of patients treated with streptokinase and in 58% of those receiving alteplase. The mean time to thrombolysis was shorter among those treated with alteplase (22 vs 40 hr). Among the 5 patients treated with alteplase who had a major or intracranial bleed, 3 received the highest dose (2.5 mg/hr). (The duration of treatment was not indicated.) Two major bleeds occurred in the remaining 64 patients treated with the low doses.

-