Practice Essentials

Facial soft-tissue injuries are not uncommon in athletics. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] The position and anatomy of the face make it particularly vulnerable to trauma. In addition, few sports mandate the use of protective equipment, leaving the face susceptible to injury. [9] Although most such injuries are minor in nature, they should be evaluated promptly with a focused history and thorough examination (see the image below). In addition, facial injuries should be treated early to reduce the likelihood of possible adverse outcomes (ie, infection, loss of function, poor cosmesis). In this article, common sports-related soft-tissue facial injuries are discussed, with an emphasis on the initial evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. [10, 11]

Signs and symptoms

The face is extremely vascular, and even minor injuries may result in profuse bleeding. Note the location, size, shape, and depth of any lacerations, and explore wounds for foreign bodies. Palpate for areas of crepitus or bony step-off. Gross asymmetry may signify underlying nerve damage. Assess neurologic function by evaluating sensation and motor function.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Facial injuries in which there is significant bony tenderness or obvious deformity warrant imaging to evaluate for fractures. Start with plain films of the face; panoramic x-ray images may also be of benefit. If the clinical suspicion is high or plain films are inconclusive, computed tomography scans can be useful.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

A systematic approach to facial laceration repair ensures the best chance at an optimum outcome. One methodological approach includes the following:

-

Wound assessment

-

Anesthesia

-

Wound cleaning and irrigation

-

Repair

-

Follow-up

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Patient education

Proper home wound care should be clearly explained to the patient and his or her family.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the United States, approximately 3 million people present to emergency departments (EDs) for treatment of traumatic facial injuries each year. Most of these injuries are relatively minor soft tissue injuries that simply require first-aid care or primary closures.

The exact frequency of facial soft-tissue injuries related to sports participation is unknown. This is, in part, due to the minor nature of many injuries, which can lead to underreporting. It may also be due to the wide variation that is seen between demographic groups and between specific sports.

Previous reports estimate sports participation to account for 3-29% of all facial injuries. [5] In terms of overall sports-related injury, facial trauma accounts for 11-40% of injuries attended to by medical professionals. Most injuries are reported in males, particularly those aged 10-29 years. Sports that mandate the use of helmets, mouth guards, and face shields tend to have fewer soft-tissue injuries compared with sports that do not mandate the use of such equipment. [12]

A study of young female athletes found that the majority of sports-related craniofacial injuries occurred in those who were aged 10-19 years. Softball (35%), basketball (28%), and soccer (16%) were responsible for most of these injuries. The most frequently encountered types of craniofacial injury were contusions, abrasions, and lacerations. [9] A study of youth baseball athletes aged 5-19 years showed that the most common type of craniofacial injury was facial contusion, which represented 25% of all such injuries. [13]

Sport-Specific Biomechanics

Most facial soft-tissue injuries are the result of direct trauma. The mechanism of facial soft-tissue injuries is often a direct impact from an external source (eg, sporting equipment, another participant, environment/playing surface). The forces exerted by the impact can lead to friction, shear, compression, and/or traction of the soft tissue and underlying structures. Injury patterns vary widely by sport, based on various factors (eg, rules, equipment). [14, 15, 16]

Prognosis

The prognosis for most facial soft-tissue injuries is good; the injuries usually heal rapidly, allowing the athlete to return to play. Knowing the expectations of the athlete and the athlete's family is important to ensure the treatment result is optimal.

Complications

Facial soft-tissue injury complications include, but are not limited to, the following:

-

Infection

-

Hematoma

-

Poor cosmesis

-

Flap/wound edge necrosis

-

Nasal septum necrosis

-

Retained foreign body

-

Cauliflower ear

-

Loss of function

See Treatment for more detail about complications.

-

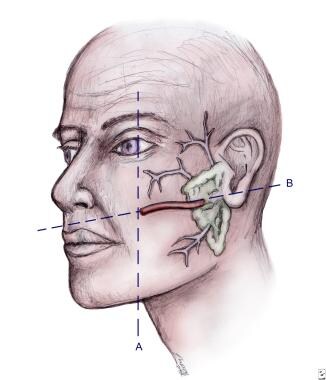

Location of the parotid gland and duct system.

-

Distribution of nerves for regional anesthesia of the face.

-

Steps to repair lip laceration. A 3-layered approach is needed, as depicted.

-

Top: Improper repair of an angled laceration. Bottom: Proper repair of an angled laceration, with creation of perpendicular edges for a flush repair.