Background

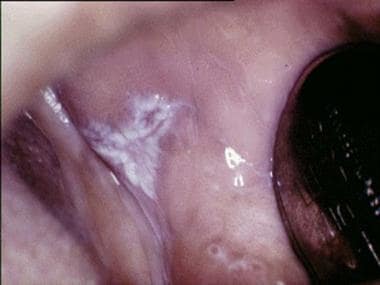

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic mucocutaneous disorder that presents in a wide range of clinical forms, including unilateral or bilateral white striations, papules, or plaques on the buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, tongue, and gingiva. (See the image below.) Erythema, erosion, and blisters may or may not be present.

Pathophysiology

Evidence suggests that OLP is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease in which autocytotoxic CD8+ T cells trigger apoptosis of oral epithelial cells. [1, 2, 3]

The dense subepithelial mononuclear infiltrate in OLP is composed of T cells and macrophages, and there are increased numbers of intraepithelial T cells. Most T cells in the epithelium and adjacent to the damaged basal keratinocytes are activated CD8+ lymphocytes. Therefore, early in the formation of OLP lesions, CD8+ T cells may recognize an antigen associated with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I on keratinocytes. After antigen recognition and activation, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells may trigger keratinocyte apoptosis. Activated CD8+ T cells (and possibly keratinocytes) may release cytokines that attract additional lymphocytes into the developing lesion.

OLP lesions contain increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. [4] Basal keratinocytes and T cells in the subepithelial infiltrate express TNF in situ. [5] Keratinocytes and lymphocytes in cutaneous lichen planus (LP) express elevated levels of TNF receptor I (TNF-RI). [6] T cells in OLP contain mRNA for TNF and secrete TNF in vitro. [7] Serum and salivary TNF levels are elevated. [8, 9] TNF polymorphisms have been identified in OLP patients and may contribute to the development of additional cutaneous lesions. [10] Successful treatment with thalidomide, a drug known to suppress TNF production, has been reported. [11, 12] These data implicate TNF in the pathogenesis of OLP.

Elevated concentrations of interleukin (IL)-6 and neopterin in saliva and serum of patients with the erosive-atrophic form of OLP suggest that these substances may be involved in the etiology of this variant. [13] Some research has suggested that osteopontin, CD44, and survivin may be involved in the pathogenesis of OLP as well. [14] Additionally, microRNA 4484 (miR-4484) has been found to be significantly upregulated in the salivary exosomes of patients with OLP. [15]

Although the specific antigen that triggers LP is unknown, it may be a self-peptide (or altered self-peptide), in which case LP would be a true autoimmune disease. The role of autoimmunity in the pathogenesis is supported by many autoimmune features of OLP, including the following:

-

Chronicity

-

Onset in adults

-

Predilection for females

-

Association with other autoimmune diseases

-

Occasional tissue-type associations

-

Depressed immune-suppressor activity

-

Presence of autocytotoxic T-cell clones in lesions

The expression or unmasking of the LP antigen may be induced by drugs (lichenoid drug reaction), contact allergens in dental restorative materials or toothpastes (contact hypersensitivity reaction), mechanical trauma (Köbner phenomenon), viral infection, or other unidentified agents. [16, 17, 18]

Etiology

OLP is believed to be a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease in which autocytotoxic CD8+ T cells trigger the apoptosis of oral epithelial cells. However, its precise cause is unknown.

Reported associations between OLP and systemic diseases may be coincidental, given that (1) OLP is relatively common, (2) OLP occurs predominantly in older adults, and (3) many drugs used in the treatment of systemic diseases trigger the development of oral lichenoid lesions as an adverse effect.

In many patients, a cause for the oral lichenoid lesions cannot be identified; in these patients, the disease is called idiopathic OLP.

Oral lichenoid drug reactions may be triggered by systemic drugs including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), beta blockers, sulfonylureas, some angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and some antimalarials. In patients with oral lichenoid lesions, it is important to be alert for any systemic drug as a cause.

Oral lichenoid contact-sensitivity reactions may be triggered by contact allergens, including dental amalgam composite resin and toothpaste flavorings, especially cinnamates. Skin patch testing may help in identifying contact allergens (see Other Tests). If an allergy is detected, lesions may heal when the offending material is removed.

Oral lichenoid lesions may be triggered by mechanical trauma (Köbner phenomenon) from calculus deposits, sharp teeth, rough surfaces of dental restorations or prostheses, cheek or tongue biting, or oral surgical procedures. Any teeth associated with OLP lesions should be scaled to remove calculus deposits and reduce sharp edges. Dental restorations and prostheses that are associated with OLP lesions should be mirror-polished.

Some studies have shown an increased incidence of Candida albicans infection in OLP, an increase that is more notable in erosive OLP than in nonerosive OLP. [19] The nature of the relation between C albicans infection and OLP remains to be fully elucidated.

Some studies have revealed a prevalence of viral (eg, hepatitis C virus [HCV] infection) infections in OLP. Some studies have reported human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6, 11, 16, or 18. [20, 21] Dysplastic OLP lesions had a higher prevalence of HPV-16 than nondysplastic OLP lesions.

Some study findings have suggested an association between OLP and chronic hepatic diseases such as HCV infection, autoimmune chronic active hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis. [22, 23] This association probably reflects the geographic distribution of HCV disease and lichenoid reactions to various drug therapies (eg, interferon alfa for HCV disease and penicillamine for primary biliary cirrhosis). OLP is associated with HCV infection and liver disease in parts of Japan and southern Europe. An association between OLP and HCV infection has not been detected in British, French, German, Scandinavian, or American patients.

Oral lichenoid lesions may arise in people who habitually chew betel quid. A causal role for betel quid in OLP has not been established.

Oral lichenoid lesions are part of the spectrum of chronic graft-versus-host disease that occurs after allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation.

No consistent association with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) has been reported in OLP. Thus, the patient's genetic background appears not to play a critical role in OLP pathogenesis.

Exacerbations of OLP have been linked to periods of psychological stress and anxiety. [24, 25]

There is little evidence to support a connection between diabetes mellitus (DM) and OLP. The oral lichenoid lesion in Grinspan syndrome (triad of OLP, DM, and hypertension) is probably an adverse effect of the drug therapy for DM and hypertension.

Epidemiology

US and international statistics

OLP has been estimated to affect approximately 1-3% of the general adult population, though in many areas, the precise prevalence of the disease is unknown. A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis (46 studies; N = 654,956) by Li et al yielded estimated global prevalence figures of 0.89% in the general population (15 studies; n = 462,993) and 0.98% in clinical patients (31 studies; n = 191,963). [26]

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

OLP predominantly occurs in middle-aged adults; younger adults and children can be affected, but rarely. [27] The meta-analysis by Li et al found that in five of the clinic-based studies providing age distribution data, the prevalence of OLP was 0.62% in patients younger than 40 years and 1.90% in patients aged 40 years or older. [26] A multicenter European study (N = 565) found that the average age at diagnosis of OLP was 60.11 years. [28]

The female-to-male ratio for OLP has been estimated at approximately 1.4:1. In the previously cited meta-analysis, the prevalence of OLP in the population-based studies was 1.55% in women vs 1.11% in men, whereas the prevalence of OLP in the clinic-based studies was 1.69% in women vs 1.09% in men. [26]

OLP affects all racial groups.

Prognosis

OLP is a mucosal subtype of LP. Whereas cutaneous LP lesions typically resolve within 1-2 years, the reticular forms of OLP have a mean duration of 5 years, and erosive OLP lesions are long-lasting and persist for up to 15-20 years or, in some cases, even longer. Resolution of the white striations, plaques, or papules is rare. Symptomatic OLP (ie, atrophic or erosive disease) characteristically waxes and wanes, though the associated white patches rarely resolve. Patients with atrophic (erythematous) or erosive (ulcerative) disease commonly have significant local morbidity. This condition can be aggravated by stress and can have a significant negative impact on quality of life. [29]

Immunosuppressive therapies usually control oral mucosal erythema, ulceration, and symptoms in OLP patients, with minimal adverse effects. However, it may prove necessary to try a range of therapies.

Patients with OLP should be followed at least every 6 months for clinical examination and repeat biopsy as required, though patients should be advised to seek medical care whenever symptoms are exacerbated or the presentation of the lesions changes. OLP has a potential malignant transformation in the range of 0.04-1.74%, as reported in the literature, [28] though there has been controversy regarding the etiopathogenesis of this transformation. Careful, regular long-term follow-up is essential for early detection of malignant transformation. [30]

In the context of appropriate medical care, the prognosis for most patients with OLP is excellent; the condition typically is well controlled by topical or systemic therapies.

Patient Education

Patient education is important. Many patients with OLP are concerned about the possibilities of malignancy and contagiousness, and many are frustrated by the lack of available patient education concerning their condition.

Patients with OLP should be informed regarding the following:

-

The chronicity of the condition and the expected periods of exacerbation and quiescence

-

The aims of treatment—specifically the elimination of mucosal erythema, ulceration, pain, and sensitivity

-

The lack of large randomized controlled therapeutic clinical trials

-

The possibility that several treatments may have to be tried

-

The potentially increased risk of oral cancer

-

The possibility of reducing the risk of oral cancer

Patient-oriented information and support can be accessed online (eg, from the Texas A&M School of Dentistry's International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group).

Patient education material is available in the Cancer Center, as well as Cancer of the Mouth and Throat.

-

Plaquelike oral lichen planus on buccal mucosa on left side.

-

Reticular oral lichen planus on buccal mucosa on left side.

-

Ulcerative oral lichen planus on dorsum of tongue.

-

Lichen planus nail involvement.