Practice Essentials

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by the absence of esophageal peristalsis and impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) in response to swallowing. The LES is hypertensive in about 50% of patients. These abnormalities cause a functional obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ).

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of achalasia include the following:

-

Dysphagia (most common)

-

Regurgitation

-

Chest pain

-

Heartburn

-

Weight loss

Physical examination is noncontributory.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies are noncontributory. Studies that may be helpful include the following:

-

Esophageal manometry (the criterion standard): Incomplete LES relaxation in response to swallowing, high resting LES pressure, absent esophageal peristalsis; classify achalasia subtypes by the Chicago Classification to help inform prognosis and treatment plan

-

Prolonged esophageal pH monitoring to rule out gastroesophageal reflux disease and determine if abnormal reflux is being caused by treatment

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy to rule out cancer of the GEJ or fundus

-

Concomitant endoscopic ultrasonography if a tumor is suspected

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The goal of therapy for achalasia is to relieve symptoms by eliminating the outflow resistance caused by the hypertensive and nonrelaxing LES.

Pharmacologic and other nonsurgical treatments include the following:

-

Administration of calcium channel blockers and nitrates decrease LES pressure (primarily in elderly patients who cannot undergo pneumatic dilation or surgery)

-

Endoscopic intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin to block acetylcholine release at the level of the LES (mainly in elderly patients who are poor candidates for dilation or surgery)

Surgical treatment includes the following:

-

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy, preferably with anterior (Dor; more common) or posterior (Toupet) partial fundoplication

-

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)

Patients in whom surgery fails may be treated with an endoscopic dilation first. If this fails, a second operation can be attempted once the cause of failure has been identified with imaging studies. Esophagectomy is the last resort.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Sir Thomas Willis described achalasia in 1672. In 1881, von Mikulicz described the disease as a cardiospasm to indicate that the symptoms were due to a functional problem rather than a mechanical one. In 1929, Hurt and Rake realized that the disease was caused by a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax. They coined the term achalasia, meaning failure to relax.

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by the absence of esophageal peristalsis and impaired LES relaxation in response to swallowing. [1] The LES is hypertensive in about 50% of patients. These abnormalities cause a functional obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction. See the images below.

Achalasia. Barium swallow demonstrating the bird-beak appearance of the lower esophagus, dilatation of the esophagus, and stasis of barium in the esophagus.

Achalasia. Barium swallow demonstrating the bird-beak appearance of the lower esophagus, dilatation of the esophagus, and stasis of barium in the esophagus.

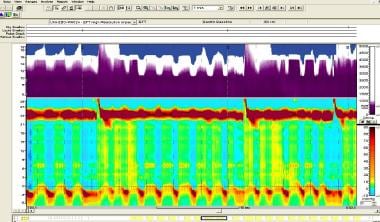

Achalasia. High-resolution manometry of patient with achalasia type I. Top one third (in purple) represents fluid-filled esophagus by impedance, with incomplete emptying between swallows. Below this, upper horizontal dark-red band represents upper esophageal sphincter; orange band at bottom with interspersed dark-red areas represents lower esophageal sphincter. In between these two bands, it can be noted that there is no panesophageal pressurization and no peristalsis in the esophageal body. Image courtesy of R Matthew Gideon, Albert Einstein Medical Center.

Achalasia. High-resolution manometry of patient with achalasia type I. Top one third (in purple) represents fluid-filled esophagus by impedance, with incomplete emptying between swallows. Below this, upper horizontal dark-red band represents upper esophageal sphincter; orange band at bottom with interspersed dark-red areas represents lower esophageal sphincter. In between these two bands, it can be noted that there is no panesophageal pressurization and no peristalsis in the esophageal body. Image courtesy of R Matthew Gideon, Albert Einstein Medical Center.

Pathophysiology

Although much is known about the factors that contribute to achalasia, the exact pathogenesis remains unclear. [1] Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and relaxation are regulated by excitatory (eg, acetylcholine, substance P) and inhibitory (eg, nitric oxide, vasoactive intestinal peptide) neurotransmitters. Persons with achalasia lack nonadrenergic, noncholinergic, inhibitory ganglion cells, causing an imbalance in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. [2, 1] The result is a hypertensive nonrelaxed esophageal sphincter.

Etiology

There is some evidence that achalasia is an autoimmune disease. [2, 3, 4] A European study compared immune-related deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in persons with achalasia with that of controls and found 33 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with achalasia. All of the were found in the major histocompatability complex region of chromosome 6, a location associated with autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis, lupus, and type 1 diabetes. [3, 4]

Epidemiology

United States incidence

The incidence of achalasia is estimated to be approximately 1.6 per 100,000 people per year. It is likely higher owing to misdiagnoses of heartburn and chest pain. [1, 5]

The incidence of esophageal dysmotility appears to be increased in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). [6] In a study of 12 patients with paraplegia (level of injury between T4-T12), 13 patients with tetraplegia (level of injury between C5-C7), and 14 able-bodied individuals, Radulovic et al found 21 of the 25 patients (84%) with SCI had at least one esophageal motility anomaly compared to 1 of 14 able-bodied subjects (7%). Among the anomalies seen in SCI patients were type II achalasia (12%), type III achalasia (4%), esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (20%), hypercontractile esophagus (4%), and peristaltic abnormalities (weak peristalsis with small or large defects or frequent failed peristalsis) (48%). [6]

Altered esophageal motility is sometimes seen in patients with anorexia nervosa. [7] It is also seen in patients following eradication of esophageal varices by endoscopic sclerotherapy, in association with an increased number of endoscopic sessions but not with manometric parameters. [8] Features of esophageal motility after endoscopic sclerotherapy are a defective lower sphincter and defective and hypotensive peristalsis.

International data

In a retrospective study (1990-2013) from the Netherlands, the mean incidence of achalasia in children was 0.1 per 100,000 people per year. Relapse rates after the initial treatment were higher in those who underwent pneumodilation (79%) than Heller myotomy (21%), but complications occurred more often following Heller myotomy (55.6%) than with pneumodilation (1.5%). [9]

Chagas disease may cause a similar disorder to achalasia.

Sex- and age-related demographics

The male-to-female ratio of achalasia is 1:1.

Achalasia typically occurs in adults aged 25-60 years. Less than 5% of cases occur in children.

Prognosis

Pneumatic dilation and laparoscopic myotomy are effective for managing achalasia. If adequate expertise is available, surgery is preferred.

Do not use botulinum toxin and medications if performing a pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic Heller myotomy.

-

Achalasia. Barium swallow demonstrating the bird-beak appearance of the lower esophagus, dilatation of the esophagus, and stasis of barium in the esophagus.

-

Achalasia. Manometric evaluation of the esophagus in a patient with achalasia. Pertinent findings include absence of propulsive peristalsis in the body of the esophagus (note simultaneous contractions), elevated resting lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, and the absence of LES relaxation.

-

Achalasia. Heller myotomy extending 1.5 cm onto the gastric wall.

-

Achalasia. Dor fundoplication, left row of sutures (after division of short gastric vessels).

-

Achalasia. Completed Dor fundoplication.

-

Achalasia. High-resolution manometry of patient with achalasia type I. Top one third (in purple) represents fluid-filled esophagus by impedance, with incomplete emptying between swallows. Below this, upper horizontal dark-red band represents upper esophageal sphincter; orange band at bottom with interspersed dark-red areas represents lower esophageal sphincter. In between these two bands, it can be noted that there is no panesophageal pressurization and no peristalsis in the esophageal body. Image courtesy of R Matthew Gideon, Albert Einstein Medical Center.

-

Achalasia. High-resolution manometry of patient with achalasia type II. Top one third (in purple) represents fluid-filled esophagus by impedance. Bottom two thirds (in orange) represents pressurized esophagus. Dark-red band at top of orange area represents upper esophageal sphincter (UES); dark-red band at bottom represents lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Note isobaric simultaneous contractions and elevated intraesophageal pressure (orange area) along with impaired LES relaxation (high resting pressure and incomplete relaxation). Image courtesy of R Matthew Gideon, Albert Einstein Medical Center.

-

Achalasia. High-resolution manometry of patient with achalasia type III. Top one third represents impedance portion of study. In bottom two thirds, in between orange horizontal bars representing upper and lower esophageal sphincters, vertical bands that represent esophageal body contractions can be seen. Note areas that are equivalent to spastic contraction, which can even obliterate esophageal lumen. Image courtesy of R Matthew Gideon, Albert Einstein Medical Center.