Practice Essentials

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a sequela of streptococcal infection—typically following 2 to 3 weeks after group A streptococcal pharyngitis—that occurs most commonly in children and has rheumatologic, cardiac, and neurologic manifestations. [1, 2] The incidence of ARF has declined in most developed countries, and many physicians have little or no practical experience with the diagnosis and management of this condition. Occasional outbreaks in the United States make complacency a threat to public health.

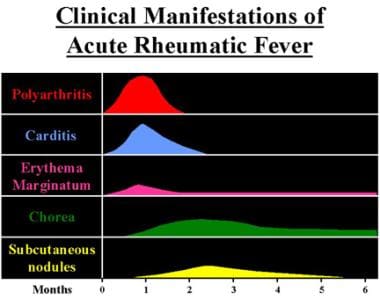

Diagnosis rests on a combination of clinical manifestations that can develop in relation to group A streptococcal pharyngitis. [3] These include chorea, carditis, subcutaneous nodules, erythema marginatum, and migratory polyarthritis. (See the image below.) Because the inciting infection is completely treatable (see Treatment), attention has refocused on prevention.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of ARF and rheumatic heart disease is complex and not fully understood. It involves bacterial factors, host susceptibility, molecular mimicry, and aberrant innate and adaptive immune responses in the host. [4]

Molecular mimicry is thought to account for the tissue injury that occurs in rheumatic fever. Both the humoral and cellular host defenses of a genetically vulnerable host are involved. In this process, the patient's immune responses (both B- and T-cell mediated) are unable to distinguish between the invading microbe and certain host tissues. [4]

Streptococcal antigens that are structurally similar to those in the heart include hyaluronate in the bacterial capsule, cell wall polysaccharides (similar to glycoproteins in heart valves), and membrane antigens that share epitopes with the sarcolemma and smooth muscle. Studies have shown a correlation between antibodies against streptolysin O, a cytolytic toxin elaborated by group A streptococci, and antibodies against human cardiac myosin. [5] Sydenham chorea in ARF is likely due to autoantibodies reacting with brain ganglioside. [6] The resultant inflammation may persist well beyond the acute infection and produces the protean manifestations of rheumatic fever.

Genetics may contribute, as evidenced by an increased familial incidence. No significant association with class I human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) has been found, but a higher frequency of the class II HLA antigens DR2 and DR4 has been found in Black and White patients, respectively. [7] Evidence suggests that elevated immune complex levels in blood samples from patients with ARF are associated with HLA-B5. [8]

A meta-analysis of 13 studies suggested that carriage of the HLA-DRB1*07 allele increases susceptibility to ARF/rheumatic heart disease, while carriage of the HLA-DRB1*15 allele protects against it. The frequency of the HLA-DRB1*07 allele was significantly higher in patients compared with controls (odds ratio [OR] = 1.68, P< 0.0001), and the frequency of the HLA-DRB1*15 allele was significantly lower (OR = 0.60, P = 0.03). [9]

Meta-analyses of candidate gene studies suggest that theTGF-β1 [rs1800469] and IL-1β [rs2853550] single-nucleotide polymorphisms contribute to susceptibility to rheumatic heart disease. [10]

In a study of 15 patients with rheumatic heart disease and a control group of 10 patients who had been exposed to group A streptococci but did not develop either ARF or rheumatic heart disease, 13 genes were differentially expressed in the same direction (predominantly decreased) between the two groups. Seven of those were immune response genes involved in cytotoxicity, chemotaxis, and apoptosis. The researchers concluded that the high proportion of differentially expressed apoptotic and immune response genes supports a model of autoimmune and cytokine dysregulation in ARF. [11]

ARF often produces a pancarditis, characterized by endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. Endocarditis manifests as mitral and aortic valve insufficiency. Severe scarring of the valves develops during a period of months to years after an episode of ARF, and recurrent episodes may cause progressive damage to the valves. The mitral valve is affected most commonly and severely (65-70% of patients); the aortic valve is affected second most commonly (25%).

The tricuspid valve is deformed in only 10% of patients, almost always in association with mitral and aortic lesions, and the pulmonary valve is rarely affected. Severe valve insufficiency during the acute phase may result in congestive heart failure (CHF) and even death (1% of patients). Whether myocardial dysfunction during ARF is primarily related to myocarditis or is secondary to CHF from severe valve insufficiency is not known. When pericarditis is present, it rarely affects cardiac function or results in constrictive pericarditis.

Chronic manifestations occur in adults from residual and progressive valve deformity. Rheumatic heart disease is responsible for 99% of mitral valve stenosis in adults, and it may be associated with atrial fibrillation from chronic mitral valve disease and atrial enlargement

Etiology

In temperate climates, ARF typically follows pharyngitis from certain strains of group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). The overall rate of ARF after streptococcal pharyngitis is 0.3-3%. However, genetically predisposed individuals, comprising perhaps 3%-6% of the population, account for those who develop rheumatic fever. [12]

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci are gram-positive organisms that frequently colonize the skin and oropharynx. They may cause suppurative diseases (eg, pharyngitis, impetigo, cellulitis, myositis, pneumonia, puerperal sepsis). Direct contact with oral or respiratory secretions transmits the organism, and crowding enhances transmission. Patients remain infected for weeks after symptomatic resolution of pharyngitis and may serve as a reservoir for infecting others. Penicillin treatment shortens the clinical course of streptococcal pharyngitis and more importantly prevents the major sequelae.

The group A streptococcal strains associated with ARF are heavily encapsulated and rich in M protein (signifying virulence). Of the 230 serotypes of group A Streptococcus, the classic rheumatogenic strains include emm types 1, 3, 5, 6, 14, 18, 19, 24, 27, and 29. More recent data suggest that many other group A emm types may also be involved. [12, 13]

However, in Aboriginal communities of Australia, where reported rates of ARF and rheumatic heart disease are among the highest in the world, throat colonization with group A Streptococcus is uncommon, and symptomatic group A Streptococcus pharyngitis is rare; skin infection (pyoderma) is the major manifestation of group A streptococcal infection. Group C and G streptococci, which have been shown to exchange key virulence determinants with group A Streptococcus, are more commonly isolated from the throats of Aboriginal children. [12] A study in an animal model also provided evidence that group G streptococci can induce and/or exacerbate ARF and rheumatic heart disease. [14]

Scabies can lead to skin sores and secondary streptococcal infection, providing a pathway to ARF. [15] A study from New Zealand documented that children who had been diagnosed with scabies were 23 times more likely to develop ARF or chronic rheumatic heart disease, compared with children who had no scabies diagnosis. Even after adjustment for confounders in a Cox model, the association remained strong, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 8.98 (95% confidence interval: 6.33-20.2). [16] Subsequently, Thornley et al reported that permethrin prescribing, as an indicator of scabies, is strongly associated with the incidence of ARF. [17]

Epidemiology

United States

The incidence of an acute rheumatic episode following streptococcal pharyngitis is 0.5-3%. The peak age is 6-20 years. The incidence of ARF in the US declined markedly over the course of the 20th century: In the early 1900s, the incidence was reportedly 5-10 cases per 1000 population, and currently it is less than 2 cases per 100,000 school‐aged children annually. [18]

While the incidence of ARF has steadily declined, the mortality rate has declined even more steeply. Credit for the decline can be given to improved sanitation and antibiotic therapy. Nevertheless, while rheumatic fever in the 21st century appears to be largely a disease of crowding and poverty, several sporadic outbreaks in the United States could not be blamed directly on poor living conditions; new virulent strains are the best explanation.

In Hawaii, the incidence of ARF has remained several times higher than in the continental United States, particularly among ethnic Polynesians. Unusual group A streptococci emm types that are uncommon in the continental United States appear to play a significant role in the epidemiology of ARF in Hawaii. [19]

International

Worldwide, as many as 20 million new cases of ARF occur each year, predominantly in developing countries. The introduction of antibiotics has been associated with a rapid worldwide decline in the incidence of ARF. Currently, the incidence is 0.23-1.88 patients per 100,000 population. From 1862-1962, the incidence per 100,000 population declined from 250 patients to 100 patients, primarily in teenagers.

Most major outbreaks occur under conditions of impoverished overcrowding where access to antibiotics is limited. Rheumatic heart disease accounts for 25-50% of all cardiac admissions internationally. Rates of rheumatic heart disease and related deaths are particularly high in Oceania, South Asia, and central sub-Saharan Africa. [20] Some areas of South America are also strongly affected. [21]

Rates of ARF are exceptionally high in natives of Polynesian ancestry in Hawaiian and Maori populations. For example, in a study from a New Zealand district, the ethnicity of ARF patients was 85% Maori and 10% Pacific. Although the annual incidence of ARF was 3.1 per 100,000 population overall, in Maori children aged 5-14 years the incidence was 46.1 per 100,000 population. Almost three-quarters of all patients lived in severely socioeconomically deprived areas. [22] In Australia, the age-standardized first-ever rates of ARF were 71.9 per 100,000 population for indigenous populations, compared with 0.60 per 100,000 for non-indigenous populations. [23]

In the past decade, an increase in the incidence of ARF was observed in Slovenia, in south-central Europe. From 2008 through 2014, the estimated annual incidence of ARF was 1.25 cases per 100,000 children. [24]

A study of pediatric patients (age 0-17 years) in Lombardy, Italy who were hospitalized with the diagnosis of ARF from 2014 to 2016 found that the annual hospitalization rate was 4.24 cases per 100,000 children. A seasonal trend was evident, with fewer cases in the autumn and a peak in the spring. [25]

Sex- and age-related demographics

No general clear-cut sex predilection for ARF has been reported, but certain of its manifestations seem to be sex variable. For example, chorea and tight mitral stenosis occur predominantly in females, while aortic stenosis develops more often in males.

The initial attack of ARF occurs most frequently in persons aged 5-15 years. [26] It is relatively rare in infants and uncommon in preschool-aged children. ARF occurs in young adults, but the incidence of first episodes of ARF falls steadily after adolescence and is rare after age 35 years. [27] The lower rate of ARF in adults may represent a decreased risk of streptococcal infections in this cohort. Recurrent episodes, with their predisposition to cause or exacerbate valvular damage, occur until middle age. In some countries, a shift into older groups may be a trend.

Prognosis

After a first attack of ARF, the course is highly variable and unpredictable. Approximately 90% of episodes last less than 3 months. Only a minority persist longer, in the form of unremitting rheumatic carditis or prolonged chorea. The outcome of carditis is likely to be more severe in patients with pre-existing heart disease. Carditis resolves without sequelae in 65-75% of patients.

Joint inflammation can take up to a month to resolve without treatment but almost never causes lasting damage. In very rare cases, the arthritis may result in periarticular fibrosis, the so-called Jaccoud joint.

Sydenham chorea typically lasts several months and resolves completely in most patients, though about one-third experience recurrences.

In an Australian study, recurrence of ARF occurred most often in the first year after initial ARF episode (incidence 3.7 per 100 person-years), but low-level risk persisted for more than 10 years. Risk of progression to rheumatic heart disease was also highest in the first year (incidence 35.9%), almost 10 times higher than that of ARF recurrence. [28]

Carditis causes the most severe clinical manifestation because heart valves can be permanently damaged. The disorder also can involve the pericardium, myocardium, and the free borders of valve cusps. Chronic valvular disease may develop even in patients who initially recovered without signs of valvular damage. Death or total disability may occur years after the initial presentation of carditis. Worldwide, the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease may range from 33 to 78 million cases, and deaths from rheumatic heart disease may range from 275,000 to 1.4 million deaths each year. [29]

Patient Education

Patients and parents should be educated to seek medical attention upon the first signs of pharyngitis. Once the disease is established, patients should be educated regarding benefits and risks of compliance with their medical regimen, which may be protracted.

-

Clinical manifestations and time course of acute rheumatic fever.

-

Chest radiograph showing cardiomegaly due to carditis of acute rheumatic fever.

-

Erythema marginatum, the characteristic rash of acute rheumatic fever.