Practice Essentials

Vasculitis may involve any organ system in the body, and may involve small, medium, or large blood vessels. Cutaneous vasculitis can present in several forms, as follows [1] :

-

A cutaneous component of systemic vasculitis

-

A skin-predominant variant of systemic vasculitis

-

A single-organ vasculitis of the skin

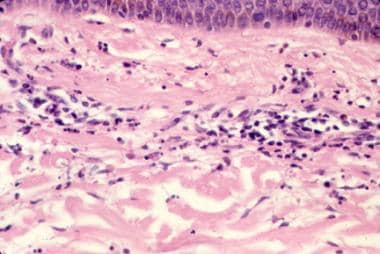

This article focuses on small-vessel vasculitis (SVV) that affects the skin. This includes cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis (CSVV), which is a single-organ vasculitis affecting the small vessels of the skin, previously termed hypersensitivity vasculitis. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a histopathologic finding that is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation of the small postcapillary venules of the dermis leading to leukocytoclasis (vascular damage caused by nuclear debris from the infiltrating neutrophils). LCV is the common histologic finding of SVV in the skin, regardless of whether the vasculitis is skin-predominant or systemic (see the image below). [2]

Classically, small-vessel vasculitis in the skin presents as palpable purpura (see the image below). The primary lesion is palpable due to inflammation, and purpuric due to extravasation of red blood cells, indicative of the underlying vascular damage. Less common morphologies include urticarial lesions, inflammatory retiform purpura, [3] (shallow) erosions and ulcers, as well as hemorrhagic vesicles, bullae, and pustules. Deep ulcers, large areas of necrosis or retiform purpura, nodules, and livedo reticularis or racemosa are clinical signs that medium or large vessels may be involved. The internal organs most commonly affected in SVV are the joints, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and kidneys.

Cases of SVV affecting the skin may be idiopathic or may be secondary to systemic vasculitis, infections, medications, or other identifiable causes. See Etiology.

Typically, SVV with cutaneous involvement is acute and self-limited. However, approximately 10% of patients will have persistent or recurrent disease. [2, 4] Complications include ulceration and post-inflammatory changes in the skin, as well as end-organ damage in cases associated with systemic involvement. Overall, however, patients have a favorable prognosis, particularly those without internal involvement.

Patients with SVV that primarily involves the skin should be treated with nontoxic modalities whenever possible. Elevation of the legs or use of compression stockings may be helpful because the disease often affects dependent areas. NSAIDs, analgesics, or antihistamines can be used for symptomatic relief of burning, pain, and pruritus. Treatment of the underlying trigger or cause may speed improvement. See Treatment for details.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), a specific subtype of cutaneous vasculitis warranting separate discussion, is characterized by IgA-mediated vessel injury. The classic clinical finding of palpable purpura in HSP is often preceded by viral respiratory illness. HSP is more common in children but can also occur in adults and is currently better identified as IgA vasculitis. [1] Children may develop systemic disease with GI, joint, and/or kidney involvement. [5] In adults, arthritis and kidney disease occur more frequently. [6] HSP in adults, especially older men, may be associated with malignancy. [7] For full discussion of HSP, see IgA Vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

A newer classification category, IgM/IgG vasculitis (non-IgA), is yet to be fully delineated but was noted in the 2017 dermatologic addendum to the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference. [1, 8]

Pathophysiology

Immune complex deposition, with resultant neutrophil chemotaxis and release of proteolytic enzymes and free oxygen radicals, is a key component in the pathophysiology of cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis. [9, 10] When systemic disease is present (such as in vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCA]), other mechanisms may contribute. [11]

Etiology

Approximately 70-80% of adult patients presenting with biopsy-proven LCV have skin-limited disease (cutaneous small vessel vasculitis). [12, 13, 4] In a recent series, about 12% had IgA vasculitis (according to the classic HSP definition, with palpable purpura, nephritis, and GI involvement). Approximately 8% had other systemic vasculitides (such as cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, connective tissue disease, ANCA-associated vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, or Behcet disease). [13] In an older series, of 120 adult patients with primary cutaneous vasculitis, 39 (33%) had HSP and 11 had essential mixed cryoglobulinemia; 25% of patients had a systemic vasculitis (eg, polyarteritis nodosa [PAN], granulomatosis with polyangiitis [GPA], eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis [EGPA], connective tissue disease). [12]

In skin-limited cases of LCV, about 50-60% are idiopathic, about 25% are thought to be secondary to medications, and upwards of 10% of cases are post-infectious. Other causes may be attributed to underlying connective tissue diseases, illicit drug use, systemic vasculitis (such as ANCA-associated vasculitis presenting with LCV), and malignancy. [14, 13, 15, 16, 17] Sporadic reports of vaccine-induced LCV exist. [18, 19]

Virtually any medication may lead to development of LCV. Antibiotics, particularly beta-lactam drugs, are most commonly implicated and in these cases identifying whether the medication or infection is primarily responsible for development of LCV may be impossible. [16] NSAIDs, allopurinol, and immune checkpoint inhibitors are also notable triggers. [20] Monoclonal antibody therapy, such as with rituximab, is associated with serum sickness, which may present clinically with vasculitis. [21]

Levamisole, an immunomodulatory and anti-helminthic agent withdrawn from the United States market, is present in a high percentage of cocaine in the US. Levamisole-adulterated cocaine may lead to retiform purpura and mimic ANCA-associated vasculitis, particularly GPA. Often, patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy present with both MPO and PR3 antibodies, and 70% of patients in a recent review tested positive for antiphospholipid antibodies. [22] Early biopsies of levamisole-induced lesions tend to show vasculopathy/microvasculiar occlusion, suggesting this as the primary etiology, with vasculitis develping in more established lesions.

Infections that may be associated with vasculitis include the following:

-

HIV infection is associated with some cases of LCV; in addtion, SVV has been posited as an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) related to antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection. [23]

-

Hepatitis C virus was a commonly recognized cause of LCV, likely through the presence of cryoglobulins. [26] This has become more rare with the advent of highly effective therapies for hepatitis C. [27]

LCV with cutaneous involvement may also be a sign of systemic disease. Collagen vascular diseases, in particular rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus, may have an associated vasculitis, as may dermatomyositis and sarcoidosis. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease [28] ) may be associated with SVV. Treatments for IBD, in particular tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, have also been associated with vasculitis in these patients. [29, 20]

Cutaneous vasculitis with LCV may be the presenting sign of systemic vasculitidies such as IgA vasculitis (formerly HSP); cryoglobulinemic vasculitis; and ANCA-associated vasculitis, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Polyarteritis nodosa may present with systemic disease or as a more limited cutaneous form, and is generally thought of as a predominantly medium-vessel vasculitis; histologically, vasculitis may affect small arteries in the subcutaneous fat and extend to arterioles at the dermal subcutaneous junction (but not post-capillary venules). [30]

SVV presenting in the skin may be associated with underlying solid-organ or hematologic malignancy, though overall numbers are low (around 2-4%). [16, 13, 25, 31, 32] Lymphoproliferative diseases, such as multiple myeloma and myelodysplastic syndrome, may be more common culprits. [33, 34] In one series, paraneoplastic SVV was found more commonly in older patients with constitutional symptoms and in those with anemia and immature cells on peripheral blood smears. [31]

Epidemiology

SVV with skin predominance (LCV) is reported to occur in 10-30 persons per million annually. Many of the estimates come from Spanish cohorts. [35, 36, 37, 16, 13, 38] Cutaneous LCV has been reported more frequently in males. [16, 13]

Prognosis

Typically, SVV with cutaneous involvement is acute and self-limited. However, approximately 10% of patients will have persistent or recurrent disease. [2, 4] One series noted recurrent or chronic disease in 36 of 82 patients (44%). [17] Complications include ulceration and post-inflammatory changes in the skin as well as end-organ damage in cases with associated systemic involvement.

A review from Germany of prognostic markers in 28 inpatients with non-IgA single-organ cutaneous SVV found that disease manifestation on the upper extremities strongly predicted the absence of severe disease. [39]

The overall prognosis in patients with cutaneous vasculitis depends primarily on the underlying syndrome and/or the presence of end-organ dysfunction. In many patients with isolated cutaneous SVV the condition will be self limited, and treatment may be primarily supportive (see Treatment). Prognosis will be greatly affected by the presence of systemic disease (additional end-organ involvement beyond the skin) and/or the underlying trigger. In the case of infections, mortality may be more likely related to infectious complications than the vasculitis itself. [25]

-

Palpable purpura in a patient with small-vessel vasculitis.

-

Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

-

Histopathology of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

-

Urticarial vasculitis. Lesions differ from routine urticaria (hives) in that they last longer (often >24 h), are less pruritic, and often resolve with a bruise or residual pigmentation.

-

Erythema elevatum diutinum, a rare cutaneous vasculitis.