Practice Essentials

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is at least 3 cm in diameter. There is general agreement that AAAs with a diameter of 5.5 cm or greater in males and 5.0 cm or greater in females should undergo prophylactic repair. [1, 2]

In the United States, 15,000 deaths per year are attributed to abdominal aortic aneurysms. AAAs occur most commonly in individuals between 65 and 75 years of age. They often do not cause any symptoms and are found incidentally on physical examination or imaging examinations of the abdomen. [3, 4, 5] Since 1951, when Dubost first performed repair of an AAA with a homograft, surgery has been the mainstay of treatment. Approximately 40,000 patients undergo aneurysmorrhaphy each year. Many refinements in technique have occurred during the interval, but none as significant as the stent-graft.

Prevalence is 1.3% in persons older than 50 years, with an incidence over 12% in elderly men. Ruptured aneurysms are associated with a very high mortality, ranging from 50 to 95%, and mortality increases by 1% with each subsequent minute, necessitating prompt diagnosis and intervention. [5] AAA ruptures are estimated to be responsible for about 200,000 deaths per year worldwide. [6, 7, 8]

Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair is undertaken in men with an aneurysm of 5.5 cm or more and in women with an aneurysm of 5.0 cm or more.

Radiography

Calcification of the abdominal aortic wall is frequently evident on plain radiographs of the abdomen, as demonstrated in the images below. Calcification is best seen on lateral views when the spine does not obscure the opposing walls of the vessel. When calcification can be clearly identified in the opposing aortic walls, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) can be diagnosed with the plain radiographic findings.

Radiograph shows calcification of the abdominal aorta. The left wall is clearly depicted and appears aneurysmal; however, the right wall overlies the spine. Because both walls must be calcified for a diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm, lack of a clear view of the right wall makes diagnosis uncertain.

Radiograph shows calcification of the abdominal aorta. The left wall is clearly depicted and appears aneurysmal; however, the right wall overlies the spine. Because both walls must be calcified for a diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm, lack of a clear view of the right wall makes diagnosis uncertain.

The lateral view clearly shows calcification of both walls. Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be diagnosed with certainty.

The lateral view clearly shows calcification of both walls. Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be diagnosed with certainty.

If the classic eggshell appearance is present, the degree of confidence is approximately 100%; however, this finding is present only in 50% of patients. Occasionally, only the anteroposterior or lateral abdominal image demonstrates the findings clearly. If AAAs are suspected, perform abdominal US or CT for confirmation. As such, negative plain radiographic findings do not exclude the diagnosis in any way.

A tortuous, calcified aorta can mimic AAA unless both walls can be seen clearly. If the opposing walls are not calcified, the diagnosis cannot be made with certainty. In these cases, US, CT, or MRI must be performed if AAA is clinically suspected.

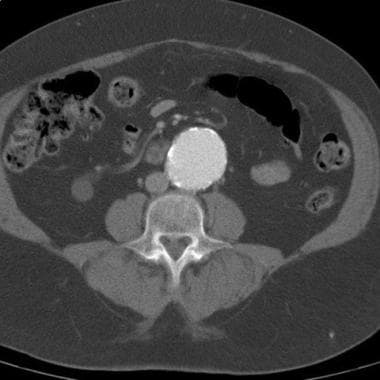

Computed Tomography

Accurate measurement of the AAA diameter is essential and has been found to be most reliably achieved by CT using a multiplanar reformat strategy. [21] CT scanning accurately demonstrates dilation of the aorta and involvement of major branch vessels proximally and distally. This information helps determine the appropriate intervention, which may be either surgical or endovascular repair. CT has emerged as the diagnostic imaging standard for the evaluation of AAA, with an accuracy that approaches 100%. A well-performed CT examination can reveal the extent of the aneurysm, as well as the involvement of other organs. Intravenously administered contrast agent is needed to obtain the full benefit of CT; however, a nonenhanced study accurately depicts AAAs. Three-dimensional reconstructions of state-of-the-art, multidetector-row, helical CT scans can help in preoperative planning and may replace the need for preoperative diagnostic angiography. [22, 23, 15, 24, 25]

(See the CT image of AAA below.)

CT demonstrates an abdominal aortic aneurysm. The aneurysm was noted during workup for back pain, and CT was ordered after the abdominal aortic aneurysm was identified on radiographs. No evidence of rupture is seen.

CT demonstrates an abdominal aortic aneurysm. The aneurysm was noted during workup for back pain, and CT was ordered after the abdominal aortic aneurysm was identified on radiographs. No evidence of rupture is seen.

CT also shows the other organs in the abdomen and demonstrates involvement or displacement of organs that can confuse the clinical picture. The location and number of the renal arteries, caliber of the aneurysm, degree of calcification, lengths of the neck and iliac artery, and presence of mural thrombus are readily assessed. CTA allows multiplanar assessment of the aneurysm and associated relevant vessels (visceral arteries, iliac and femoral arteries).

The administration of contrast material is essential for detecting dissection or ulceration of a vessel that might be missed without it. In the acute setting (eg, in a patient with back pain or an aneurysm), a false-positive diagnosis of rupture is possible if fluid resulting from another cause is seen in the abdomen. Conversely, an aneurysm or rupture can be missed in a patient who has recently undergone a barium study, because artifact can obscure the aorta.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI and MRA can be used to define the extent of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). The absence of iodinated contrast material and radiation are advantages of this modality. However, MRI is more sensitive to motion than is CT, because a patient must remain motionless for a longer period than with current multidetector-row helical CT technology. In addition, the remaining organs in the abdomen are not seen as well on MRIs because of motion. [25] (See the image below.)

MRI of a 77-year-old man with leg pain believed to be secondary to degenerative disk disease. During evaluation, an abdominal aortic aneurysm was discovered.

MRI of a 77-year-old man with leg pain believed to be secondary to degenerative disk disease. During evaluation, an abdominal aortic aneurysm was discovered.

In technically well-performed MRI and MRA, degree of confidence approaches 100%. These examinations clearly reveal the extent of the aneurysm. If prior abdominal surgery has been performed and if metal clips or devices were used, MRI may not be possible. If the metal is close to the aneurysm or if branch vessels or heavy calcification is seen, artifacts may obscure the vessel and result in a nondiagnostic study.

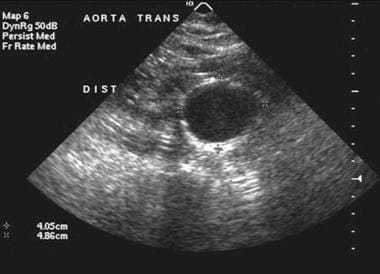

Ultrasonography

US is the screening examination of choice as a result of its relative availability, speed, and low cost. US is operator dependent, unlike other modalities; therefore, operator experience is important. The abdominal aorta normally tapers as it extends distally. Any increase in its diameter is considered abnormal. [26] (See the image below.)

Ultrasonogram of a patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This aneurysm was best visualized on a transverse or axial image. The patient underwent a conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ultrasonography is the screening examination of choice to evaluate patients for AAA.

Ultrasonogram of a patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This aneurysm was best visualized on a transverse or axial image. The patient underwent a conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ultrasonography is the screening examination of choice to evaluate patients for AAA.

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends a one-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography in men who are 65-75 years of age and have a history of smoking (ever smoker: at least 100 cigarettes during lifetime). They also recommend selectively offering screening for mean 65-75 years of age who do not have a smoking history. They recommend against routine screeing in women who have never smoked and feel there is insufficient evidence to recommend screening in women who are 65-75 years of age and have a smoking history. [14, 15]

Degree of confidence

If the abdominal aorta can be seen in its entirety, US provides a reliable, low-cost screening examination. However, in a patient who is obese or in whom the bowel is distended with gas, a complete examination of the aorta and proximal iliac arteries may not be technically possible. In such instances, another cross-sectional imaging study, such as CT or MRI), should be obtained.

Angiography

Angiography is often ordered for preoperative evaluation in patients with manifestations of atherosclerotic vascular disease, such as renal artery stenosis or peripheral vascular disease.

Compared with other images, arteriograms (shown below) currently enable better longitudinal measurements of aneurysms. The reason is that the catheters that are used to make these measurements follow the contour of the vessels and therefore allow better determination of the length of the aneurysm, as opposed to linear measurements obtained with CT. This information is not an issue in open surgical repair; however, it is important in endovascular repair.

Arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. This arteriogram was obtained in preparation for an endovascular repair of the aneurysm. There are coils in the right internal iliac/hypogastric artery. This was done to prevent retrograde filling of the aneurysm as the right limb of the endograft will cover the origin of the vessel.

Arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. This arteriogram was obtained in preparation for an endovascular repair of the aneurysm. There are coils in the right internal iliac/hypogastric artery. This was done to prevent retrograde filling of the aneurysm as the right limb of the endograft will cover the origin of the vessel.

Lateral arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Demonstration of the superior mesenteric artery, inferior mesenteric artery, and celiac artery on the lateral arteriogram is important to completely evaluate the extent of the aneurysm.

Lateral arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Demonstration of the superior mesenteric artery, inferior mesenteric artery, and celiac artery on the lateral arteriogram is important to completely evaluate the extent of the aneurysm.

Catheters with radiopaque graduated markers are used, allowing measurement of the lengths of the aneurysm and the caliber of the vessel. These data are occasionally important for endograft placement, and they may not be clear from CT and CTA. Typically, 7-10 measurements are required to size an endovascular graft to an abdominal aortic graft. Much, if not all, of the sizing can be accomplished with thin-section, contrast-enhanced CTA.

As CT algorithms for measuring aneurysms improve, the need for preoperative angiography will decrease. Angiography may be reserved for the most complex aneurysms in which endovascular repair is contemplated.

Angiography is often linked to embolization of the internal iliac artery in a patient in whom the procedure is necessary prior to endovascular repair. Examples of relevant conditions include an internal iliac artery aneurysm or an ectatic aneurysm ipsilateral to a common iliac artery that requires anchoring of the stent-graft in the ipsilateral external iliac artery.

Degree of confidence

When abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is suspected, it is unlikely to be missed at angiography. In most cases, the morphology of an aneurysm can be clearly defined. If an aneurysm is suspected on the arteriogram, a cross-sectional image should be obtained. Not only will it confirm the existence of an aneurysm, but other pathologic conditions that may affect the surgical intervention can be detected.

If a large amount of luminal thrombus is present, the true diameter of the aneurysm may be obscured unless the wall of the aneurysm has a substantial amount of calcification. This limitation leads to significant underestimation of the diameter of the aneurysm.

-

Radiograph shows calcification of the abdominal aorta. The left wall is clearly depicted and appears aneurysmal; however, the right wall overlies the spine. Because both walls must be calcified for a diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm, lack of a clear view of the right wall makes diagnosis uncertain.

-

The lateral view clearly shows calcification of both walls. Abdominal aortic aneurysm can be diagnosed with certainty.

-

CT demonstrates an abdominal aortic aneurysm. The aneurysm was noted during workup for back pain, and CT was ordered after the abdominal aortic aneurysm was identified on radiographs. No evidence of rupture is seen.

-

Arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. This arteriogram was obtained in preparation for an endovascular repair of the aneurysm. There are coils in the right internal iliac/hypogastric artery. This was done to prevent retrograde filling of the aneurysm as the right limb of the endograft will cover the origin of the vessel.

-

Lateral arteriogram demonstrates an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Demonstration of the superior mesenteric artery, inferior mesenteric artery, and celiac artery on the lateral arteriogram is important to completely evaluate the extent of the aneurysm.

-

Arteriogram after successful endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

-

Ultrasonogram of a patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. This aneurysm was best visualized on a transverse or axial image. The patient underwent a conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ultrasonography is the screening examination of choice to evaluate patients for AAA.

-

MRI of a 77-year-old man with leg pain believed to be secondary to degenerative disk disease. During evaluation, an abdominal aortic aneurysm was discovered.